“The usual brand of Camp Perry weather at this time of the year has been handed out by the weather man since camp officially opened, consisting of hot clear days and cool balmy nights.”

—Arms and the Man, September 1922

Despite the previous year’s record-shattering scores and strides made toward improved arms and ammunition, a cloud of uncertainty and post-war complacency hung over the conduct of this year’s National Matches, which were again slated to be held at Camp Perry. Pleas to Congress from the National Board went unheeded and in July, just two months from the start of the National Match schedule, Arms and the Man carried notices that no government funding would be available for civilian or National Guard teams.

A situation that very easily could have turned disastrous was averted through the NRA’s determination and persistence to encourage shooters to attend the National Matches despite the partial loss of government funds. With the NRA’s help, the National Matches were scheduled, albeit in September for the same reason cited in 1921—a conflict with the Ohio National Guard’s July matches. And the fact that the government’s decision on appropriations was not made until July left September as the only viable option. The late announcement also did not allow much time for the affected shooters to find the extra money—especially civilians, many of whom already were faced with the challenge of securing the extended leave from work.

So for the first time since the 1915 National Matches, federal funds were not available to civilian teams and the only states represented this year were Illinois and Indiana, most likely because travel expenses were nominal given their close proximity to Camp Perry. Approximately 200 unattached non-service competitors were on hand and despite the cutbacks, 32 states sent National Guard teams and the nine Corps Areas were represented by Civilian Military Training Camps (CMTC) teams, whose makeup had been granted through a congressional act two years earlier that established the CMTC for instruction of United States civilians in marksmanship.

Some who made their way to the matches despite the governmental slight were rewarded with impressive victories. A highlight of the matches was the win by the Massachusetts National Guard team in the Herrick Trophy Match, which in addition to some of the unofficial teams, exceeded the existing high score over the Palma course. (Note: Match rules prohibited more than one official team entry each from regular service, National Guard, and civilian from shooting for record.)

Civilian shooter Loren Felt of Illinois won the Leech Cup with a perfect 105 score and 10 Vs under the new scoring method adopted as the result of the 1921 National Match perfect scoring frenzy. And in the President’s Match, Capt. Edgar W. King of the Coast Artillery finished atop the field while the historic Wimbledon Cup was won for the third time by veteran shooter Capt. Guy H. Emerson of Ohio with a perfect 100 and 15 Vs. The phenomenal shooting in this event the year before by George “Dad” Farr with an issued military arm led to the NRA’s decision to classify the match and award a place to the high shooter with an “as issued” service rifle. This year there were 147 service and 33 special heavy barreled or telescopic sighted guns and the high service award went to Pvt. Louis Klinger of the Cavalry with a score of 100 with eight Vs.

In the Board matches, the Marine team defended its national title with the 1903 Springfield loaded with 170-grain boat-tailed, gilding metal-jacketed bullets sans tin. And as in 1921, conditions called for 10-member teams to fire the same course, except that 10 shots instead of 20 were fired at 600 yards. Coast Artillery Sgt. Otto Bentz topped the 780-man field in the Individual Rifle Match that again did not include a 1,000-yard stage, while honors on the pistol side went to Infantry Lt. Eduardo Andino. Fifty-yard firing returned to the pistol competition and comprised the final stage versus the first as was the case in prior years, and the Marines were successful in their national team title defense. The Board’s 1921 experiment with a separate match at Camp Perry for intercollegiate shooters did not carry over, although this year the printed program contained information about an Interscholastic and Intercollegiate Rifle Match for competition at the various Reserve Officers’ Training Corps training sites under the direction of Corps Area commanders. And like the other Board events, the college matches were conducted “under regulations prescribed by the Secretary of War.”

Just three entries comprised the police team competition, as two units from Detroit, Mich., and one from nearby Toledo, Ohio, made the trip. Toledo won the match and it was apparent in these early years of police competition that firearm training was a new concept, evident not only by the minimal entries, but by post-match reports stating that the Detroit teams had no experience with automatics and the event was the Toledo squad’s first exposure to timed and rapid firing.

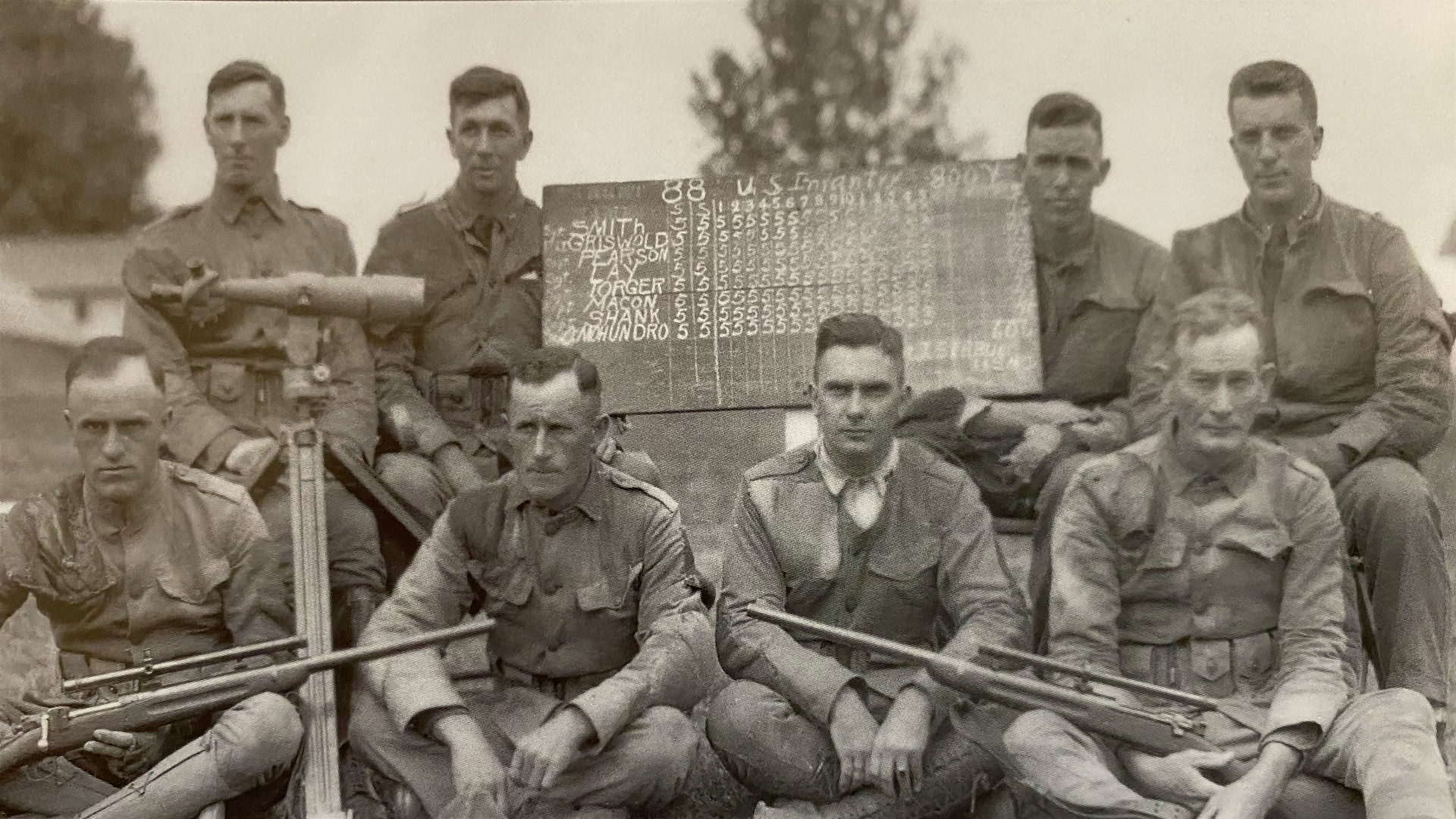

Lt. Col. Morton Mumma served his fourth year as Executive Officer of the National Matches and in appreciation, the National Rifle Association presented him with a silver pitcher for his efficient and successful leadership. Under Mumma’s guidance, a number of firsts were instituted this year. Overall, it was the first time that the National Matches were conducted without any schedule change or weather-related delays. Specifically, visitors along Commercial Row saw tents that were lighted with electricity for the first time. In addition to the employment of the new “nickel” targets, this year featured the inaugural firing of the Infantry Match, the first combat-style event since the surprise fire and Evans Skirmish matches from earlier years. Conversely, an unfortunate first occurred away from the firing range when a competitor, 21-year-old Pvt. Michael Healsan, drowned while swimming in Lake Erie.

Despite concerns about the fate of the smallbore program this year due to the federal travel subsidy cutbacks, enough enthusiasts paid their own ways and continued to make a case for smallbore as more than a side event or diversion for big-bore shooters at the National Matches, a claim made all the more convincing with yet another U.S. Dewar win.

“… there is hardly a man in America, whatever his station in life, who cannot profit wonderfully from a visit to Camp Perry.”

—Arms and the Man, August 1922

The value and standing of the Perry veterans in local shooting communities was likened to a missionary who, imbued with the spirit, would proselytize among those who remained at home. It was their responsibility, upon returning from the National Matches, to promote shooting in general, teach others what was learned at the Small Arms Firing School and the big shoot and foster interest in the game.

The smallbore match conditions from 1921 were considered satisfactory and the same match schedule was retained. The .22 rifle had begun to attract military shooters as the added competition enabled them to stay sharp during the long winter months. Civilian Loren Felt, this year’s Leech Cup winner who traveled to Camp Perry at his own expense, drove the value of .22-caliber training home in no uncertain terms. Felt was unable to practice to any extent prior to this year’s National Matches. When the matches began, practice time and space was so limited on the center-fire ranges that Felt repaired to the smallbore facility and purchased a handful of tickets for various re-entry matches, one in which he even placed with a score of 98 out of 100. After he picked up his winnings, he made his way to the Leech Cup competition with service rifle in hand and recorded his victory. Felt’s success was no coincidence and his performance convinced many center fire shooters to rethink their attitudes toward the “mouse gun.”

Perhaps the introduction of the Springfield Model Caliber .22 rifle was the biggest news of the matches. Maj. Julian Hatcher began preliminary work on the new rifle as early as 1919 for schools, colleges and civilian clubs. The rifle was developed in cooperation with the NRA to such a degree that its stock, similar to that of the Winchester Model 52, but without the grasping grooves found on the Springfield service model, was informally known as the NRA stock. The NRA model carried Lyman 48B receiver sights and a blade front sight and was also tapped for scope blocks. During the first year of production, 2,020 of them were manufactured with the earliest released through the NRA on June 1 for $39.12, plus packing and shipping charges. The new rifle quickly got into enough hands that at least 15 of them were at Camp Perry and six were used by Dewar Team shooters or alternates.

Capt. J.E. Hauck of the Indiana National Guard won the Smallbore Marine Corps Cup Match with a score of 199 and used that performance as a springboard to capture the individual championship with a Dewar score of 395. The selection pool for the Dewar team was smaller than those of prior years, no doubt because of the Congressional cut that affected civilian participation at this year’s National Matches. Nevertheless, Dewar team captain Col. Charles Stodter, the newly appointed Director of Civilian Marksmanship, was able to round up 74 competitors to fire 40 shots each at 50 and 100 yards. The top 25 scores were then selected for a final tryout and the cut-off man was Indiana National Guard Capt. George Gawehn, a teammate of the national champion. Gawehn barely made the team as he was the 19th shooter based on final tryout scores. On team day however, he pulled out all the stops and bested such smallbore sharks as past national champions Grosvenor Wotkyns and Milo Snyder to place at the top of the score sheet with a 390. It should be noted that 10 of the 20 men on the 1922 Dewar team were civilians who, in the face of a tight-fisted Congress, paid for the privilege of being on the team.

The International Dewar match was not without its share of Camp Perry weather-related trials. The wind on firing day swept off of Lake Erie with such force that match postponement was discussed. Instead, it was decided to have two hard holders fire a few strings to gauge the effects of the wind on the tiny bullets. The results were not encouraging although team officials decided to proceed with the help of coaches, among them Leech Cup winner Felt. Coaching and hard holding paid off as the total score after 50 yards was about the same as what was fired on the final tryout day. The real test was at 100 yards and scores showed the effects of the wind. In the end the team total stood at 7685, a full 50 points less than the winning score of 1921, but still 83 points above what the British fired that year. It was with great relief that several days later the Americans learned from the official witness, Col. John Caswell, that the British score was a 7615.