“The policy of encouraging the attendance of individual competitors at the National Matches is a good one and should be perpetuated.”

—Arms and the Man, October 1921

In a repeat decision from the year prior, Camp Perry was selected over Jacksonville to host the National Matches in 1921. During the National Board’s January meeting, the majority vote went to Camp Perry based on its central location, temperate climate and the fact that most of the necessary equipment was already in storage at the Ohio facility. Other Board decisions included starting the matches in late July, but the dates were later pushed back a month to accommodate the Ohio National Guard after plans for its annual encampment and competition, originally scheduled for Camp Knox outside of Louisville, Ky., changed and required the use of Camp Perry in July.

At the urging of Camp Perry’s founding father, Gen. Ammon Critchfield, the police match that a year earlier drew minimal entries remained on the schedule, while the new DCM Director this year, Col. Charles Stodter, sought the addition of more offhand shooting to the Board Matches and also expressed his favor toward a moving target competition somewhere on the match program. Other recommendations included adding matches to attract new audiences and expanding transportation provisions from one National Guard and civilian or college team to one of each from every state. The meeting also included a Board vote to repair the Hilton Trophy which had been damaged over the years from travel.

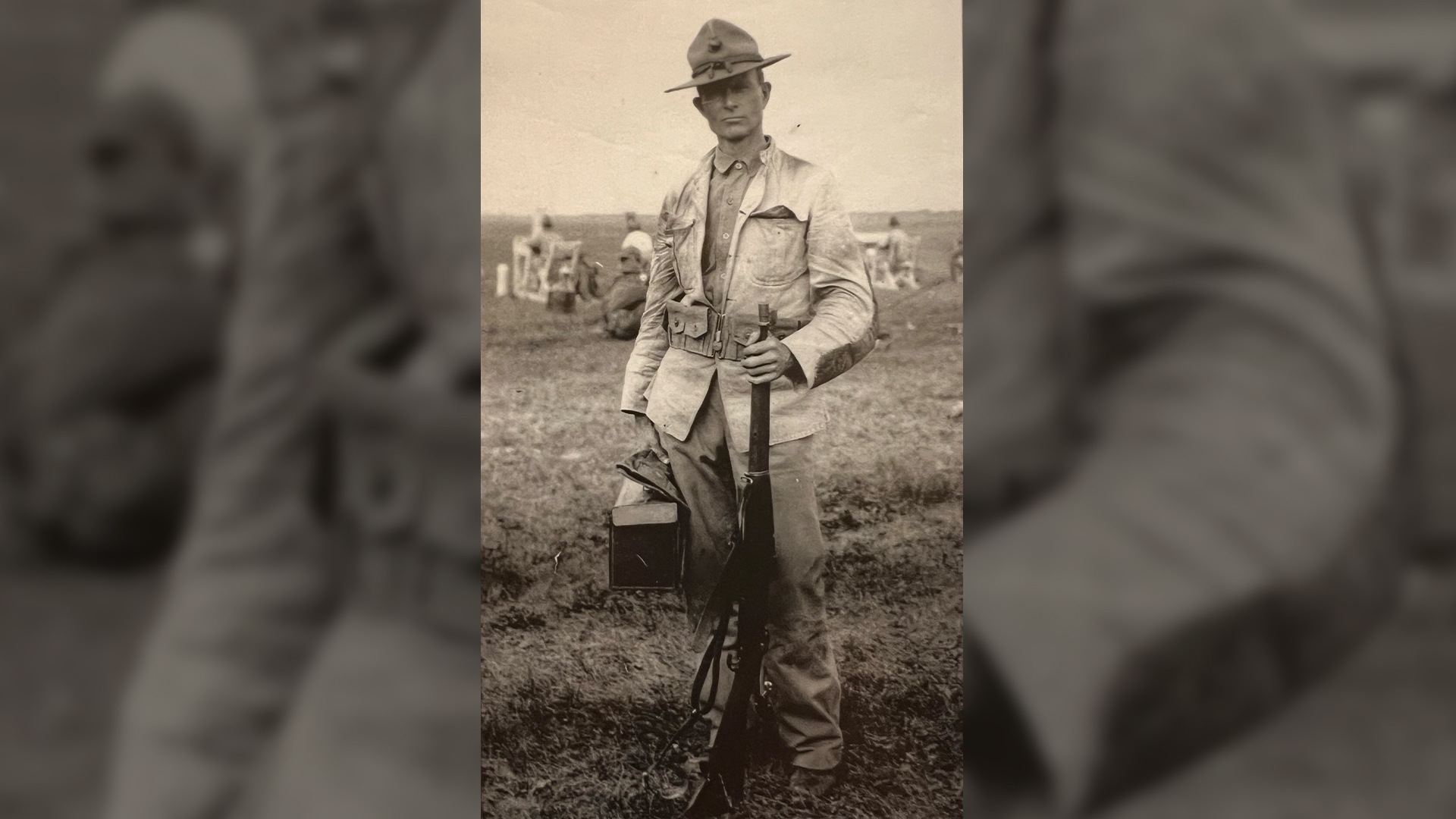

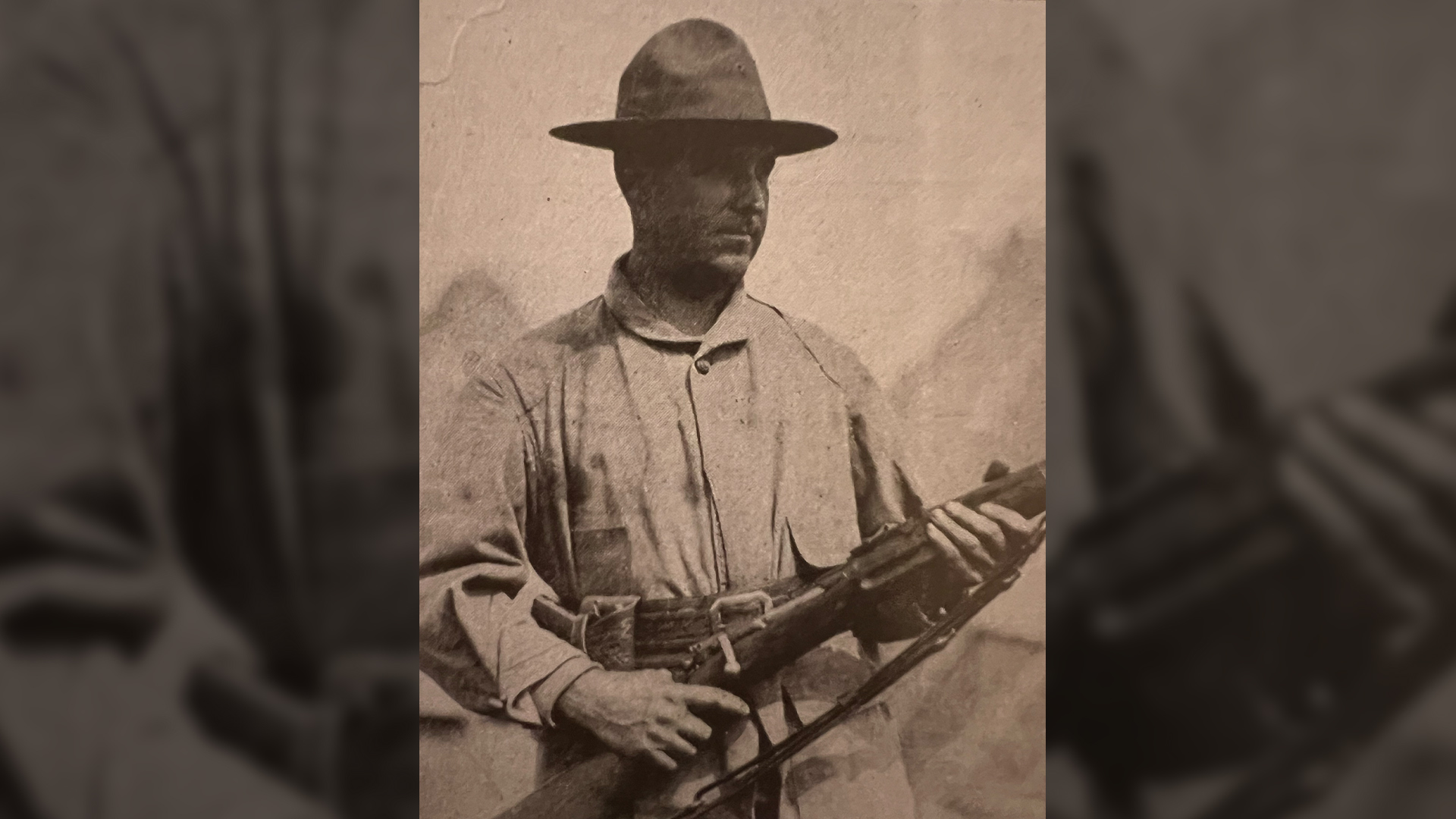

Lt. Col. Morton Mumma, in his third year as Executive Officer of the National Matches, had on his staff six former NRA presidents (Gildersleeve, Wingate, Spencer, Drain, Gaither and Libbey) in addition to the current one (Brookhart), a clear indication of the NRA’s interest and influence regarding the country’s most notable shooting event. Not surprisingly, such a strong representation further substantiates this time period as when the term “National Matches” began being used almost exclusively to promote the entire program, versus the separate references to NRA and National Board Matches—another endorsement of how the two organizational bodies had become more intertwined in their roles to advance marksmanship. The progressive connection between the two groups was unquestionably linked to changes in match policy that affected admission and allowable equipment, all of which contributed to the matches being open to a greater segment of the non-military populace.

While the National Board still emphasized the use of military arms, a broader expanse of NRA matches gave competitors the chance to whet their marksmanship appetites via the “any” provisions. Record scores this year that made possibles and long strings seem commonplace prompted calls for new targets and expanded range firing to 1,500 yards. Reasons given for the radical increase in scores were a combination of using telescopic sights, good Frankford Arsenal ammunition and new Springfield rifles considered superior to earlier rifles that had been compromised due to wartime demands.

The Winchester Cartridge Company Match was a testament to the aura of experimentation that hovered over the grounds. As reported in Arms and the Man, “When the Winchester match opened there was along that line more special equipment than has been seen in all the Wimbledon matches put together.” When the 10-shot match at 800 yards had ended, Marine Sgt. T.B. Crawley stood atop the field with a run of 176 consecutive bullseyes—his first time firing with a telescopic sight. Second place with 131 bulls went to Marine Sgt. J.W. Adkins, who earlier in the day won the Western Match with 80 straight bulls at 900 yards and, on the previous day, won the Remington Match at 1,000 yards with 71 center shots. Another notable associated with the Western Match was the performance of Mrs. E.C. Crossman, the only woman competitor in the big-bore NRA Matches to this point, who took 10th place in a field of 480 entries with a score of 50 plus 17 bulls.

Adkins singlehandedly turned heads with his string of performances in the Remington, Winchester and Western Matches, but no match this year was considered so impressive and extraordinary as the Wimbledon, which Adkins also added to his fold of victories with a record 75 bullseyes at 1,000 yards. If Adkins’ feat seemed remarkable, the one that came at the hands of the runner-up was even more so. Shooting a service rifle and sights that had been issued that day, George “Dad” Farr, 62, recorded 70 bullseyes with Frankford ammunition and left those who witnessed the event to think of the possibilities had darkness not set in.

This was the third straight year that shotgun competition was held during the National Matches and this year was the most formal offering, as the Amateur Trapshooting Association sponsored registered tournaments. The All-Round Match, created by Edward Crossman in 1919, was also held for the third time. Pennsylvania civilian Charles Hogue won the event, which featured some changes in course conditions from prior years, including 50 more clay targets for a total of 150 toward the final score. The All-Round Match also included results from pistol, smallbore and big-bore events.

On the shotgun field opposite the railway station at the entrance to camp, it was reported that 100,000 targets were thrown over a 13-day period. In addition to the instruction available, practice tickets were sold for 25 cents each, which entitled shooters to 25 targets and 25 shells. The interest generated by this affordable opportunity, coupled with the successful pistol and smallbore matches, clearly indicated an overwhelming sense of public approval for the evolving National Match program. Following through on the Board’s attempt to infuse interest among the younger age set, this year marked the addition of a fifth government match, the National Intercollegiate Rifle Team Match. The competition featured six-man teams, mirrored National Team conditions and finished with squads from the Naval Academy in the top three spots among the 18 entries.

Among the other Board matches, the Marines swept the four individual and team events. The National Individual Pistol Match was the first event fired and was done so on the new Standard American target at 25 yards only. The reason given in the match program for the omission of 50-yard firing was that the pistol, “recognized at its true value, is a firearm for defense at close quarters.”

And in a classic duel against the Infantry, the Marine team steadily recovered from a 22-point deficit to record a 15-point victory in the National Team Rifle Match—a contest that was the focus of an interesting weather-related happening when the first stage score cards were rendered illegible after a severe downpour. After the competitors gathered to resume firing, the team captains agreed to disregard the scores and start again.

This was the first time in National Match history that the individual rifle event differed drastically from the team event for reasons that officials saw as opportunities for competitors to shoot for U.S. Army qualification badges. The team match, which was reduced to 10 firing members down from 12 with half required to have had no prior National Match experience, was fired from distances of 200, 300 (new), 600 and 1,000 yards, while the individual competition was fired from 200, 300, 500 and 600 yards, the latter of which included the use of sandbag rests. It was thought that no 1,000-yard firing in the individual event and the sandbag allowance provided better chances for civilians and others to qualify for the awards.

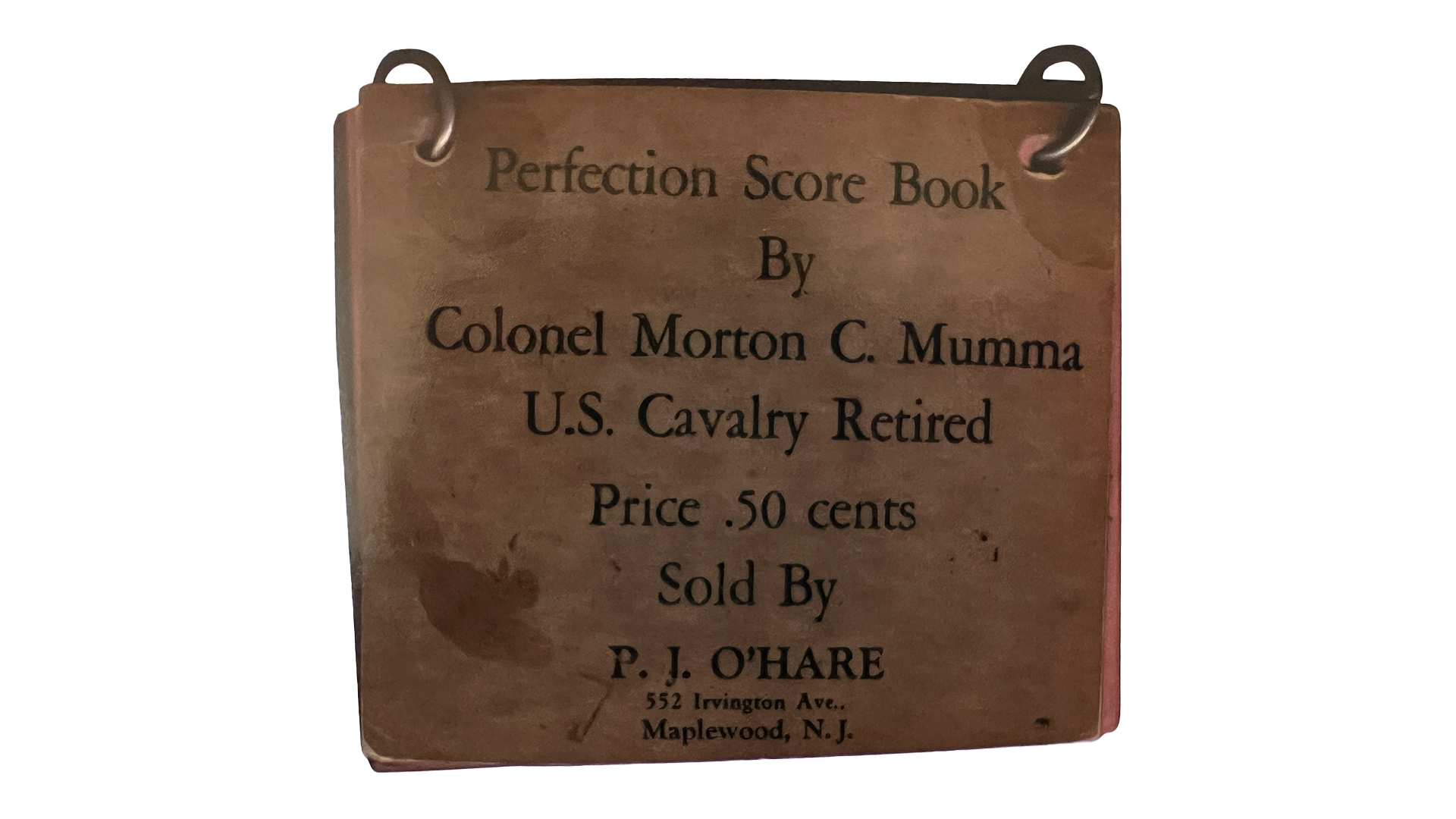

The growing interest in smallbore competition at the national level was seen as a natural culmination of the local indoor and outdoor shooting seasons. This year’s contests at Camp Perry featured a more expansive and formal approach, as the nine additional pages in the printed match program would attest. And re-entry and single-entry matches were filled to capacity despite complaints from the year before that the range, which was located next to the Erie Proving Grounds, was too far away and required detours when the 1,000-yard range was in use. Reports indicate that this year the smallbore range was to be moved to between the 200- and 600-yard firing lines and the old smallbore site was to be transformed into a pistol practice area. But due to “unforeseen circumstances” as stated in Arms and the Man, no changes took place. Any disappointment this may have caused, however, was most likely diffused by the attractive prizes that were up for grabs. Colt, Remington, Savage and Winchester furnished firearms, while Peters and Western provided ammunition and Lyman donated sights. Paddy O’Hare provided a leather shooting bag and F.W. King Optical Company offered several sets of its shooting glasses as additional prizes. The merchandise awards, coupled with the traditional medals and cash prizes, demonstrated just how much the smallbore matches had grown in size and importance.

Rules for handling targets, scoring and tiebreaking procedures were laid out and crossfires were addressed by deducting the shot value and fining the miscreant 50 cents, a fee that was collected before firing resumed. Slings were optional but a loading block was required as only the exact number of record rounds could be brought to the line. And while the British allowed but 30 seconds a shot, a more liberal—but strictly enforced—time limit of one minute per shot was allowed.

Russ Wiles, T.H. Rider and Marjorie Kinder topped the junior re-entry match as Wiles and Rider shot clean and Kinder dropped just one point. Kinder also defended her title in the standing match and showed that she was no flash in the pan. Walter Stokes, before he earned his international reputation with the free rifle in Olympic competition, was tied with Kinder at 93 but lost out on the tiebreaker.

The national title again went to the high scorer in the Smallbore Individual Match and this year was the first time that its winner, Milo Snyder of the Indiana National Guard, also won the Grand Aggregate of which the championship metallic-sight Dewar Match was a part.

The U.S. Dewar Team retained the prestigious trophy in 1921, although they did not learn until December that they defeated the British by a 100-point margin, followed by the Canadians in a distant third. In a retrospective letter to his fellow British shooters the official witness of the 1921 Dewar Match, Capt. E.J.D. Newett, indicated that the British were not at a disadvantage in skill, equipment or ammunition. Rather, he believed U.S. shooters excelled through their intense nationalism and ability to subjugate self for a common goal. Newett underscored the use by Americans of multiple selection matches and line coaching, a method the British eschewed.