This is a simple and straightforward procedure that sure seems to be misunderstood, at least based on what I see floating around online. It also, in my estimation, is a topic full of equally unclear or misinterpreted ideas centering on the whys and hows.

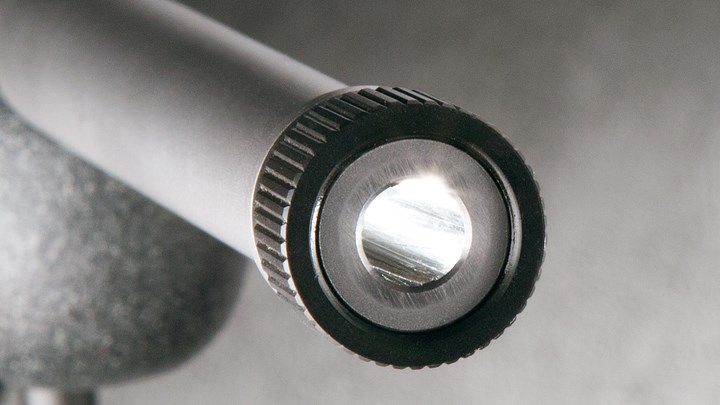

Break-in needs definition, and explanation—not just instruction. What exactly is barrel break-in? No matter who made the barrel and how carefully it was finished, there’s going to be imperfections within that only a bullet can experience. Even a hand-lapped custom barrel will at the least have a few annular tooling marks in the barrel throat residual from chambering. Lesser, lower-cost barrels are going to have more or more pronounced, often both, imperfections within the bore, all along through it. These imperfections are largely tool marks resulting from the drilling and rifling processes. And if it’s a semi-automatic, like an AR-15, there might be a burr where the gas port was drilled.

The goal of break-in is to knock down these imperfections, thereby smoothing the interior surface. That is done by exposing bare barrel steel to a bare bullet. That’s the trick. The bullet, however, isn’t really removing metal from the barrel like an abrasive treatment would—it’s just displacing it. It’s a burnishing effect. The bullet going through the barrel functions more like running a knife on a steel. It’s not the same as running the knife on a whetstone. (More about abrasives later.)

Breaking in a barrel means it will shoot its best sooner. It also means there won’t be as great an influence from copper fouling; the barrel won’t “foul out” as quickly in extended use.

To be clear: The reward from break-in is not longer barrel life. It’s earlier top accuracy. That means more rounds at peak accuracy. It’s a longer life of better performance.

Eventually all barrels break-in, but unless this is approached as a project, as a procedure and process—it might be worn out before it’s broken in. Again, it is running one bullet down a clean barrel that provides the burnishing effect. So, if that one bullet runs through a clean barrel each time you return to the range after the last visit, then in time the one bare bullet running against bare barrel steel will have had its effect. Only that might not happen for many, many outings, depending on how many rounds are fired between cleanings. The idea is to go ahead and get the burnishing effect in one controlled outing.

For that outing, get together loaded rounds with the longest bearing-area bullets you have and a bottle of copper solvent bore cleaner, cleaning rod guide, cleaning rod and patches.

To clean between each round, use a wet patch soaked with copper solvent. Follow the manufacturer’s suggestion, which usually instructs leaving the cleaner to soak in the bore for about 5 minutes. Then run a clean patch through and look at the patch.

Copper shows up as green-blue on a patch.

Important: No metal brushes! Only patches. Clearly, a bronze/brass brush will get eaten by the solvent and always result in a green-blue patch. It’s possible to use something other than copper solvent as a cleaning agent, but then there’s more steps and more time because (one more time) you have to get down to the bare metal—no residue—to get the full effect of the bullet jacket. Even if you’re like me and don’t use copper solvent for routine cleanings, get a bottle for break-in. (I use abrasive bore paste.)

Shoot. Clean. Shoot. Clean. Rinse and repeat (actually it’s repeat and then rinse). One and only one round at a time. Gauge success, which means when to find a merciful end to this tedium, based on copper fouling extracted each time through the process. Hopefully, and if it’s a “good” barrel, after 5 to 10 rounds of shoot-and-clean, there won’t be anything showing on the patch. At that, or some point not long after regardless, shoot 5 to 6 rounds and patch-clean the barrel. That’s the “test” and if the patch comes out clean (no green-blue) that’s the end of the day. The barrel is then broken in, if it indeed will break-in. Some barrels are going to be rough enough that a bullet jacket won’t really smooth it, or not so you’ll notice.

You could shoot and clean many times over, but some barrels are still going to show fouling.

If you have fired even as many as 20 single rounds and still see fouling, consider an abrasive—or not. That’s a call I really can’t make for you. I have no worries using abrasives in my barrels, but some people do and that’s not the sort of objection that only reassuring words can allay.

The most commonly available, and I think easiest to use, is something from David Tubb’s FinalFinish System collection. This is a “fire-lapping” process using coated bullets. There are various packages for varying levels of need. Follow the instructions to the last letter and, honestly, don’t worry. The abrasive substance on the bullets is much finer grit than what a custom maker uses for hand-lapping. The “patch test” is actually a good way to know if it will help your barrel. Again, it will if you’re seeing blue after 20 rounds of shoot-and-clean.

Clean the barrel when you are back home in whichever fashion that you deem proper. And make sure there’s now something left behind between the bare metal and the air. Copper cleaner strips a bore, and that leaves it open to corrosion.

The preceding is adapted from Zediker’s book America’s Gun: The Practical AR-15. Visit www.buyzedikerbooks.com or www.zediker.com for more information plus downloads from Zediker Publishing.

See more: