The below is an excerpt from the 1978 book, Olympic Shooting, written by Col. Jim Crossman and published by the NRA. Read Part 1 and Part 2.

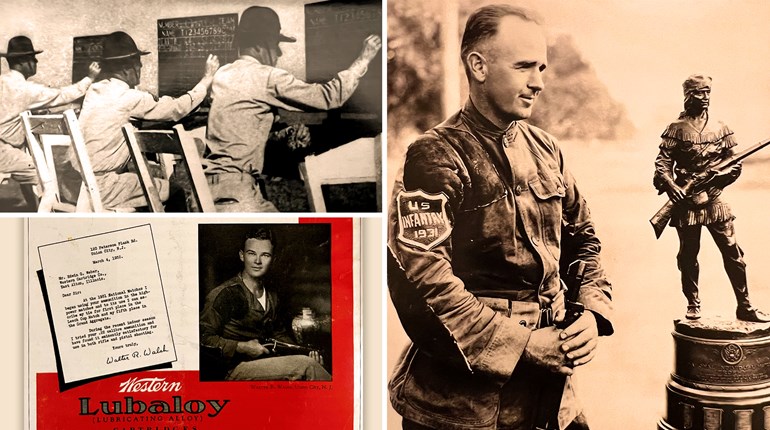

1932—Los Angeles: On U.S. Soil, But Problems Develop (Part 3)

By Colonel Jim Crossman

The rifle team tryouts in late May and early June included shooting twice over the 30-shot Olympic course, for a total of 60 shots and a possible of 600. Targets were scored on the range and the results mailed to the Olympic Rifle Committee. Final tabulation showed that Dr. E.D. Shumaker of Ohio was well ahead with the phenomenal score of 600 plus 11 additional 10s. In second place was Army Lt. Rom Stanifer with 600, while William Harding, Los Angeles, had 598. Scores of the next three shooters, chosen as alternates, dropped to 592, 591 and 589.

For team captain and manager of the pistol group, the Pistol Committee chose Col. Roy D. Jones, a well-known shot and Secretary of the U.S. Revolver Association. Mahlon E. Frank, USRA official in Southern California, was selected to coach and train these new shooters.

The team captain of the rifle group was originally Capt. E.C. Crossman, the author's father and one of the great names in the shooting game of that time.

After giving up a summer vacation and hastily driving a thousand miles to see what this match was about, Crossman soon decided that, as the NRA representative, he needed to put all his effort on straightening out this shooting match. So the team captain title fell on the capable shoulders of Ned Cutting, who was involved both in shooting and in promoting shooting. Col. W.A. Tewes, an outstanding shot in his own right starting back in the Schuetzen days and coach of many successful teams, showed up on the range one day. Then working for the Peters Cartridge Company, he had come out on a vacation to see the Olympic Games. He was persuaded to give up his vacation and take over the job as coach. He filled this job in his usual capable manner, and his calming influence and great experience were factors in getting an inexperienced American shooter finished only two points behind the winner.

The improvements to the range did not make it suitable for the Olympic shoot.The Organizing Committee in Los Angeles spent some thousands of dollars improving the Los Angeles Police Range so that it would be suitable for the Games. Unfortunately, and in line with their other operations in the shooting field, the committee did not consult the Olympic Rifle Committee or the Olympic Pistol Committee—nor apparently any other knowledgeable shooter. The improvements to the range did not make it suitable for the Olympic shoot.

The pistol range was not in bad shape. Although designed with concrete below-ground pits at 25 yards, it was possible to move the firing line back to 25 meters. The firing line was concrete, with a raised area behind for spectators. The six turning targets, built on a structure raised out of the pits, operated reasonably well. Unfortunately, early in the affair the Italian coach stepped on a loose board over the pit, fell into the pit and broke his hip.

But the rifle range had to be seen to be believed! In fact, most of the foreign shooters did not believe it even after they saw it. They could not believe the Americans were serious about using it and many of them flatly refused to.

A wooden structure some 90 feet long and considerably wider than the pistol shooting area was built over the built-up concrete pistol line. It was a fine cover for the pistol range, keeping sun and rain off the shooters and spectators. But it made a terrible rifle firing point. The platform quivered and shook like whipped cream on top of gelatin. The platform vibrated every time anyone took a step or a shooter changed position. One of the shooters claimed the thing moved so much that he got actively seasick during one string. But it was later concluded that he was exaggerating, as no one else was affected more than to turn slightly green.

To try to steady the platform, heavy wire cables were staked to the ground out in front of the platform, run over the top of the platform, pulled tight and staked to the ground in the rear. While this helped somewhat, it merely verified the first impression of experienced shooters that the platform was impossible.

The unusual 50-meter platform-firing line was unique in two other respects: it was not 50 meters from the newly constructed concrete pits, and it was not parallel to the line of the pits. By jamming the shooters against the black wall on one end, it was possible to get almost 50 meters, but the shooters were in imminent danger of being trampled as people walked up and down the firing line. On the other end of the platform there was lots of room, as the firing line angled across it.

At best, the distance was still short of 50 meters by a few feet. So a unique rig was worked up, in which the target sat a few feet behind the marking pit on a hinged framework. A rope fastened to the target frame pulled the frame over the hinge and somersaulted into the pit—a remarkable solution to a difficult problem!

After some time of struggling with the shaky platform and the somersaulting targets, it was decided to get down to basics—the ground. It was not possible to see the target at 50 meters, however, due to intervening pits and parapets. A group of heavy, rigid tables was built, each to be used by one shooter. The tables were high enough so that the shooter could see his target. By elbowing the pistol shooters out of the way, it was possible to get room enough for a few firing points. This made even the somersaulting targets too close, so the pits were abandoned completely and the rifle targets were mounted on fixed frames. Finally, the rifle shooters had a moderately satisfactory place to shoot.

During the match, one of the foreign shooters apparently got confused and fired a shot on the wrong target.Many foreign shooters were accustomed to shooting at a single target which was pulled into the pit after each shot, the value marked and the shot hole covered with transparent tape. The pit marking was tentative, with final scoring done later in the statistical office. So some of the shooters were not happy about the final U.S. system, which put six targets on a single frame. The left target was for sighting shots, with the others for record shots. After each series of five record shots, firing was stopped while the shot holes were covered with transparent tape. During the match, one of the foreign shooters apparently got confused and fired a shot on the wrong target. Other than this, the table and fixed target system worked reasonably well and the matches went off satisfactorily.

With 14 firing points, the rifle match was fired in two relays. Early in the first string, one of the volatile, likable Hungarians, Tony Lemberkovits, was so intent on holding for a 10 that he forgot to look for his target number and put his 10 on a target of the shooter next to him. He immediately recognized his mistake and called the range officials, who verified the fact. According to the rules, this shot had to be scored a miss—which lost Lemberkovits the Olympic Championship.

With all the scores in, Gustavo Huet of Mexico and Bertil Ronnmark of Sweden were tied for first, both with 294x300, calling for a shoot-off. While Zoltan Soos-Ruszka (Hungary) and Mario Zorzi (Italy) both had 293, Soos-Ruszka outranked the Italian according to the rules. With four competitors having scores of 292, it was necessary to shoot off to determine fifth and sixth places. With so many ties, it is obvious that the competition was tough. In fact, there was only a 13-point spread from top score to bottom score.

In settling the ties, Ronnmark came out on top as the Olympic Champion. One of his teammates, Gustaf Anderson, easily won fifth place in the shoot-off by turning in the high score of the match, 296. Another teammate, Karl Larsson, also had 292 in the match. Later, Larson became Secretary-General of the International Shooting Union and the UIT owes much of its success to him.

Of the Americans, Bill Harding, student at Stanford at the time, made the best showing. An unaccountable wide 8 hurt badly and held him to a 292.

The other American shooters were well down in the list. Big, red-headed Schumaker had a 288 while Rom Stanifer had 287. Incidentally, Stanifer shot a fine Model 52 Winchester rifle that belonged to my mother Blanche Crossman, the first woman to shoot on a U.S. International Team. Early in the practice sessions it became evident that the rifle Stanifer had brought with him, a Springfield, just was not capable of shooting up with the other rifles, so the switch was made.

Harding and Schumaker also used American rifles and ammunition, as did second-place winner Huet. While he used a Winchester Model 52 rifle and Winchester Five-Star ammunition, the other winners used German ammunition, with Ronnmark and Anderson using Danish rifles, and Soos-Ruszka and Zorzi using German rifles.

Although squeezed a little for space when the rifle shooters moved down off the roof, the pistol shooters were able to get in plenty of practice. Under the capable hands of Jones and Frank, the Americans were shooting very well, with Roberts and Carr turning in a number of possible scores clear down to the 3-second time limit, while Tippins was close on their heels.

The day of the pistol match started out bright and clear, as typical of the Southern California weather at that time of year. But it soon turned gloomy for the Americans. Tippins, showing his lack of tough match experience, dropped his first two shots off the silhouette, then settled down and ran his next 16 straight. But it was too late, and Tippins, along with two of the Spanish team and all three of the Brazilians, had to drop out of contention after the 8-second stage. One-third of the 18 starters fell by the wayside at this point, shooting one or more misses out of the 18 shots.

Of the 12 shooters who went into the 6-second stage, Tom Carr was the only one to shoot a miss.

The last American hope, Roberts, shot one miss and was eliminated.At the end of the six shots in four seconds, six shooters still had perfect scores, three from Italy, and one each from Germany, Spain and Mexico. The last American hope, Roberts, shot one miss and was eliminated. The 3-second time limit dropped three more shooters, leaving only Domenico Matteucci and Renzo Morigi of Italy, along with Heinrich Hax of Germany.

Now came the crucial 2-second stage, which was to be shot repeatedly until one shooter was left. Mind you, the shooters stood with his gun pointed down at a 45-degree angle. When the targets turned, he raised his pistol, aimed and fired a shot at the first silhouette, swung over 30 inches to the next silhouette, aimed and fired a shot and repeated this for six shots—all in two seconds.

The German Hax was the first shooter in this stage. The crowd held its breath as he rattled off six shots in that unbelievably short two seconds, to be released in a cheer when it was announced that he had made four hits. The pleasant, balding policeman, Morigi, was the second man up. It was obvious to all that he had used all his time, as his last shot hit the target while it was turning, giving him a "skidder" that nearly cut the target in half. The crowd went wild when the scorers, working their way down the targets one by one, announced "hit," "hit" until they got up to five—the sixth hit was plainly visible to all!

Morigi's teammate, Matteucci could have slowed down a bit and gone for five hits and second place, but he played it tough all the way, trying for first. He made only three hits and had to be content with third place. But it was a great performance by all three competitors and they deserved their medals.

Many of the foreign shooters arrived with German Walther and Spanish Star pistols. But after watching the Americans shooting the .22 Colt Woodsman pistol, there was a rush to the nearest gun store and practically everyone ended up shooting the Colt. It was usually doctored by taping a heavy weight under the barrel to steady the gun and cut recoil. Since no refires were allowed for malfunctions of any kind, everyone was careful to baby his pistol and to examine his ammunition carefully. Often a bit of extra lubricant was added to the bullet to, hopefully, insure proper functioning.

And so, after many trials and tribulations and despite the many handicaps, the 1932 Olympic shooting events were finally and successfully concluded. Although it was never possible to correct the mistakes of the Organizing Committee, it was possible to conduct the matches. The contrast between the shooting events and the other events was all the greater because of the great job done by the Organizing Committee in planning most of the other events.

Aside from a couple of routine protests, which were readily settled by the Jury, the matches were fired without any real problems. Both shooters and officials left with the feeling that the best possible had been done, considering the circumstances.

Since most of the other events of the 1932 Games were planned on a grandiose scale and organized magnificently, it was just too bad that the shooting events were such a fiasco. It was made worse by the fact that in Southern California there were many fine ranges and many experienced, capable shooters who could have assisted in the early planning.

But with all its faults, 1932 was a big improvement over 1928. There were shooting events in the Olympics! And they have been an important part of the program ever since.

Photo: The Los Angeles 1932 Summer Olympic Games official poster. Photo courtesy of Olympic.org.

Read more: London 1908 Olympics: The U.S. Team Almost Missed The Games