Excerpt from the 2002 book NRA: An American Legend by Jeffrey L. Rodengen.

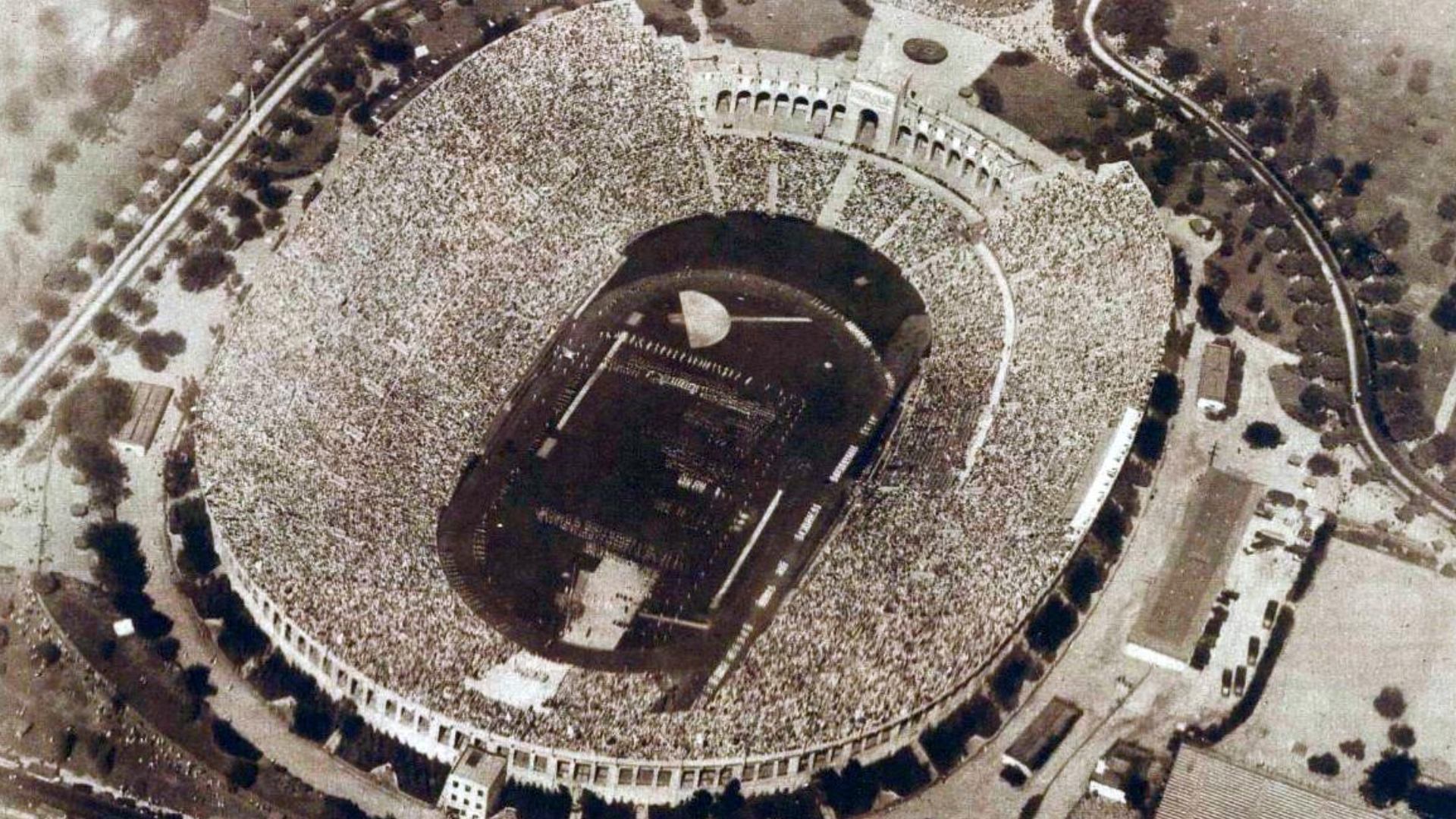

After the Olympic Games of 1924, the International Olympic Committee had eliminated all sports not of major spectator interest and those that it called "mass athletics." Among those events dropped under this ruling was shooting. The National Rifle Association and the International Shooting Union protested this decision and conducted an ongoing campaign to have rifle and pistol shooting reinstated, but their efforts remained unsuccessful until 1931, when the NRA Board of Directors appointed an Olympic Rifle Committee chaired by Milton Reckord and an Olympic Pistol Committee headed by Karl Frederick.

That same year, the International Olympic Committee ruled that it would bar from competition anyone who had accepted a cash prize or who had competed in a contest in which a cash prize had been offered. By the 1930s, cash prizes, though small, were still being issued for shooting competitions, and there was scarcely a single experienced target shooter in America or in the world who could meet the committee's standards. Both of NRA's Olympic committees were forced to draw upon unknown shooters of little competitive experience to build their teams.

The International Olympic Games Committee did not consult NRA's Olympic committees on the arrangements of the shooting match or on the construction of the shooting facilities. This slight was further complicated when the International Olympic Games Committee announced that the Sergeant of the Los Angeles Police Department would be "in charge of shooting" at the Olympic Games in Los Angeles—despite the same committee having invited NRA and the United States Revolver Association (USRA) to assume some charge of the shooting facilities.

The result was a fiasco. Although fine for police practice, the Los Angeles Police range was neither designed nor built for formal competitive shooting. When NRA's Olympic Rifle Committee reached Los Angeles, they found that the shooting house was several yards too near the 50-meter targets and out of parallel with the line of the targets. To attain 50 meters, the shooters had to press back against the rear wall so that men moving from one point to another did not interfere with those who were shooting. When the foreign teams arrived, most of them flatly refused to shoot until the range was rebuilt.

Although the Americans had bent over backwards to abide by the rules of amateurism, they soon found that their competitors had taken the rules more lightly. General Reckord and Karl Frederick had been associated with international shooting long enough to recognize men who had been shooting in international circles for years. Frederick had competed personally for cash prizes against a number of them. If they had protested, however, the entire shooting program would have been eliminated, so they decided to make the most of a bad situation.

The shooting events were a major disappointment. But at least to the shooting world, the events were better than no participation at all and they provided the basis on which future competition could be built.

Photo: Aerial shot of the 1932 Summer Olympics at the Los Angeles Coliseum. Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Public Domain.

Read more: Amsterdam 1928 Olympics: Another Games Without Shooting Events