This quest for replication likely resulted from an odd sequence of events. In 1924, the 300-meter World Championships were held in Rheims, France, just a few days before the Olympics. The U.S. was determined to show that our “win” and record scores in the previous year’s World Championship at Camp Perry, were no accident; only the U.S. team showed up (for more background see “The Roaring Twenties”, SSUSA, February 2015). Team selection and training were devoted to that end, with the Olympic matches being distinctly a secondary concern. The Olympics included, in addition to the smallbore event, running deer (in which the U.S. claimed no expertise) and long-range prone. We knew long-range, so having a smallbore rifle that replicated the larger caliber rifles would provide a bumpless transition between centerfire and smallbore.

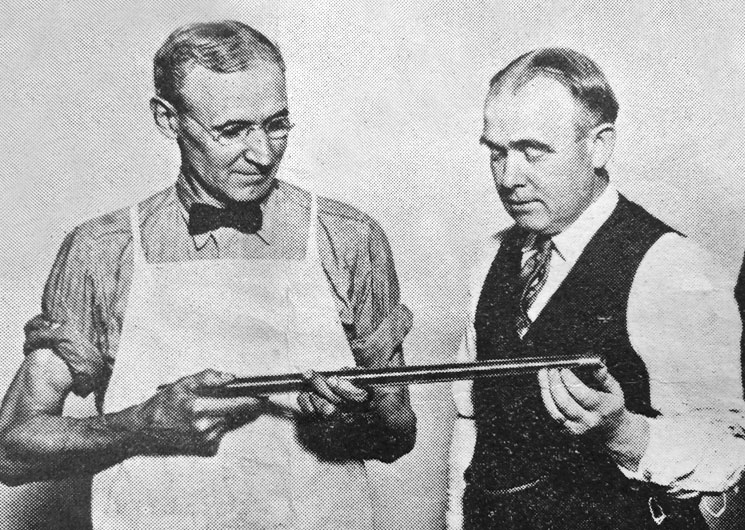

The rifle that resulted from these efforts is one of the rarest of competition rifles—a unique specimen of the gun maker’s art, a data point in the development of smallbore match rifles and ammunition that allows comparison with the performance of modern equipment and shooters.

To decrease lock time, the firing pin’s travel was reduced by one half. Although Wotkyns noted that “…in the standard weapon shortly to appear, this reduced striker time will not be attempted…”

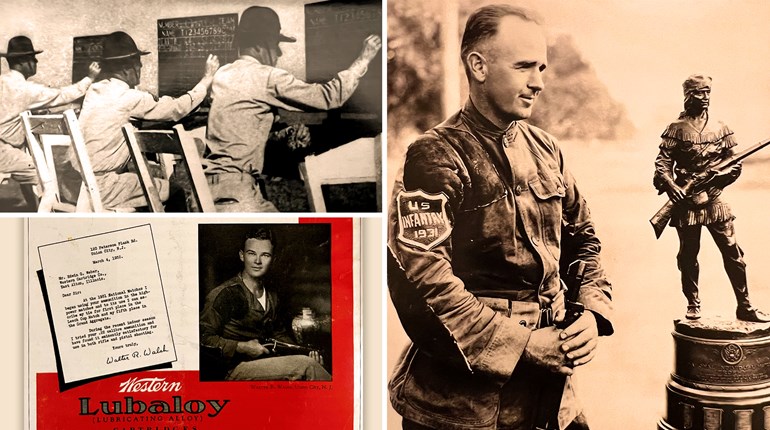

Wotkyns described the stocks as “having a rather full, high comb, extenuated (sic) pistol grip and fore-end of beaver tailed section.” All 12 rifles were designed and built at Springfield Armory in Massachusetts in 15 days.

As their contribution to the partnership, the Marine Small Arms Arsenal and Armory in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, under the direction of Major L.W.T. Waller, USMC, made the “international” accessories: set triggers, palm rests, hook buttplates and adjustable sling swivels. Wotkyns noted that the triggers were “the invention of a Marine,” presumably Frank Rimkunas, but at least one surviving rifle has an apparently original equipment trigger by G.A.Woody.

The effort to replicate the centerfire rifles was successful. William Brophy, in his magisterial book, The Springfield 1903 Rifles, asserts that “When this rifle is side by side with its caliber .30 big brother, it is difficult to tell which one is which.”

Springfield Armory’s test comprised five 10 shot machine rest groups (also combined into a 50 shot composite) fired at 50 yards. Of the 600 shots fired through the 12 rifles, 599 were within the one-inch 10-ring of the then 50-yard NRA smallbore target (the present 50-yard target, having a 0.89-inch 10-ring, was not adopted until 1927). The illustrated groups (essentially full size in the 1924 Rifleman article) are cited as “average results” of the tests; ammunition is not identified except as being “NRA of U.S. manufacture.”

The Olympic match would be a 40 shot standing competition fired with metallic sights at 50 meters on a target having a 10-ring 50 mm (1.97 inches) in diameter and, on that target, these rifles (officially called “Rifle, U.S., Caliber .22, Model 1924, International Match”) do the job for which they were designed. Still, I doubt that many of today’s smallbore shooters would be satisfied with the precision shown by these groups. Nowadays, they strive for a rifle and ammunition combination that, at 50 yards, will give a half-inch (or less) group with a tight, round center. All of these groups, centered in a scoring overlay, are “clean” on the current NRA 50-yard target, and probably give a good sense of the rifle and ammunition capabilities available in the 1920s.

It would be revealing to test these 12 rifles with the best modern ammunition. One of these rifles was sold at auction over a decade ago; the auction catalog photographs show the barrel drilled and tapped for scope blocks so the test should be easy to do—with or without a machine rest. I believe the rifle sold in the mid-twenty thousand dollar range so the test is unlikely to be made.

“... there is about to be, placed in the hands of the organized rifleman in this country, a smallbore weapon fully capable of scoring the highest possible if held truly and well, provided suitable ammunition is available”.

But it was not to be; no commercial version of these rifles was ever produced. Perhaps the smallbore community of the day was not ready for a 14 pound rifle however good it was; perhaps it would have cost too much—an earlier Rifleman article (June 1924) cited a cost of “dangerously near a cool one hundred dollars,” to produce each rifle. A standard Winchester 52 of the day cost about $50 and weighed about eight and a half pounds. These 12 rifles probably illustrate the best in smallbore rifles and ammunition in the mid-1920s, and testify to the willingness of the American shooting community to provide the best possible equipment for our international team.

In the 1924 Olympics, as it turned out, 17-year-old U.S. shooter Marcus Dinwiddie, of Washington, D.C., shot a 396 in the smallbore match; it looked as though his score would stand up for the gold, but M. De Lisle of France came through with a 398, leaving Dinwiddie the silver. Our four shooters in the event averaged 391—a score that equaled the former Olympic record set in 1920.