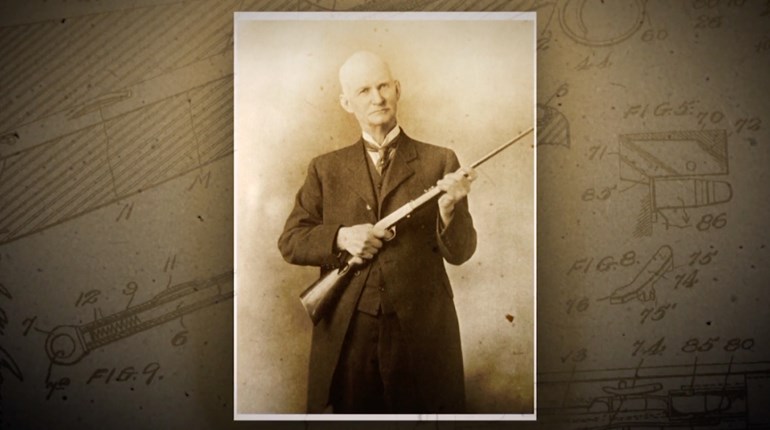

Serious competition rifles are not things of svelte and charming beauty, due to so many practical concessions toward precision shooting. However, in earlier days and at the fringe of entry level “crossover” guns there were exceptions, like the Winchester Model 69.

Every once in a while we handle a rifle that takes our breath away, as though we were the nerdy kid unbelievably receiving a kiss from the prom queen. The rifle presented here did just that. “Pristine” is the best word to describe its condition; someone spent two or three times its Blue Book value on restoration, a labor of love or sentiment, and now the rifle appears to be completely factory fresh and original. Remarkable, for an 80-year-old rimfire.

Depression concessions

Winchester introduced the Model 69 to fill the gap between its full-on target grade Model 52 and its cheaper “shooter” grade single-shot rimfires like the Model 68. It was probably a bit risky to introduce a new model during the Great Depression, but the 69 succeeded and evolved upward into later versions that earned heavier target barrels and Lyman target aperture rear sights.

And while we’re talking rear sights, let’s jump on that right now because the unusual rear sight on this Model 69 is an attention-getter. The Model 69 came standard with a barrel mounted buckhorn rear sight, but Winchester offered this receiver mounted sight as an option or as a kind of “alternate standard,” depending on the information source. Winchester employee Frederick L. Humeston filed a patent for the sight on February 20, 1934, which the U.S. government subsequently assigned to Winchester in September the following year. Unsurprisingly, it is generally referred to as “the Humeston rear sight.”

The sight is quite elegant for a collection of inexpensive stampings, a clever shot at squeezing some target grade accuracy from an adjustable sight lacking any precision machined parts. The sight consists of an aperture standing on a flat bar that pivots laterally on a central pin for windage adjustment. Rotating the horizontal thumbwheel below the aperture turns a threaded shaft (as on our AR-15 Service Rifles) that raises and lowers the back end of the entire stamped steel mount base, itself providing spring pressure. The wheel bears “0” through “5” marks between dimples that serve as stops. Neither the elevation nor windage marks appear to correspond to actual MOA adjustments, serving only as visual references, so it requires some extra trial-and-error rounds to zero the sight. More on that when we go to the range.

Petite minimalist

Winchester’s Model 69 hit the streets in March 1935. Our Model 69 here has a rebounding firing pin, a requirement for Canadian importation which Winchester incorporated in August 1935. In October 1937, Winchester began relieving the stock to make the takedown screw flush with the wood; this rifle doesn’t have that feature, placing its manufacture before then. Those two features, then, indicate Winchester made this particular rifle between August 1935 and October 1937.

The Model 69, like a great many of the older bolt action .22s, seems designed by a minimalist. The rifle is far less complicated than your fondest girlfriend, even the bolt internals being pretty intuitive. The bolt cocks on closing; a protruding cocking knob acts as the safety—pull and rotate on, pull and rotate off—with clear “SAFE” and “FIRE” legends deeply imprinted into the metal. The squared root of the bolt handle serves as the locking lug, all that’s necessary for the low pressure rimfire cartridges; on the downward stroke of the handle the “lug” rides over the rounded surface of the receiver slot, camming the bolt forward firmly into place. A pear-shaped bolt knob gives plenty of grasping surface without making it appear too large for the petite rifle.

The trigger system consists of only four parts, the trigger, sear, spring and retaining pin. Pull length is 13½ inches, and the trigger breaks at about 4½ pounds, good enough for plinking, hunting and entry level club target competition. The firing pin leaves deep indents on cartridge rims, indicating a healthy spring and plenty of pin protrusion, and ejection is positive.

The slender barrel measures 24⅞ inches from muzzle to breech face; the balance point is precisely at the takedown screw, making it a natural one-handed carry rifle. The bead-on-a-blade front sight is a ramp dovetailed into the barrel; that ramp does much to maintain the little rifle’s streamlining, a simple aesthetic point that many other rimfire rifle designers have failed to emulate. Sight radius is 27½ inches, comparing favorably to my Remington 513-T Matchmaster full-on competition rifle with a 32-inch sight radius, and certainly a positive factor in the 69’s accuracy.

A bore tour courtesy of a Lyman Borecam showed that, for this Model 69, beauty runs more than skin deep. The bore and chamber are like-new, without any evidence that the chamber has felt the fouling touch of a .22 Long or Short—or having fired any cartridge at all.

The rifle retains its original magazine with Winchester markings and a “69.” I understand the Model 69 shares the same magazine with the Models 52, 57 and 69A, but I haven’t actually tried one mag in all four guns to satisfy myself on that point. But if you’re needing a mag for one of these rifles, perhaps that multiplicity opens a few more doors for you.

There’s a wee bit of figure in the oil finished American walnut stock, and it appears to be “flame-grained” to present a somewhat tiger stripe appearance (and is a possible restoration addition, as I’m not aware Winchester did that). The buttplate fit is perfect, without gaps, overhang or “proud wood.” The Winchester logo on the composite buttplate is crisp and clear. The wood is not inlet for the stamped metal trigger guard and mag well guard, cost-saving measures that don’t detract from the rifle’s clean lines. The fore end is full, without finger grooves, and the stock has a definite pistol grip to aid in prone competitive shooting. Additionally, there is no competition rail or sling swivels, another cost-cutter.

Squirrel groups

Range day was a windless and sunny, cool autumn day a mile high in the Arizona mountains, perfect for launching ultralight .22LR bullets in a straight line. I shot from sandbag rests on a concrete bench at my gun club range, testing a variety of ammo; some groups pushed an inch and a half while others came in under an inch.

Like a hungry Depression-era kid, the little rifle isn’t a picky eater, digesting 60-grain Aguila subsonics as readily as 40-grain match and 36-grain hunting ammo. It did show a preference for Remington’s 36-grain Golden Bullet HVHP load, but every ammo offering grouped into squirrel head size groups at squirrel distance (25 yards) with the iron sights. Humeston’s rear sight windage is dead-on centered with the bore and the Golden Bullet at this distance.

With that kind of precision, we can see why the Model 69 succeeded at the range and in the field.

A winner

In November of 1937, the Model 69 morphed into the 69A. A cock-on-opening bolt, side lever safety, straight taper barrel and (somewhat) adjustable trigger differentiate the 69A from the 69. As mentioned, the 69’s precision soon warranted mounting target barrels and sights. A sightless variant intended for scopes, the Model 697, appeared in 1937 but flopped and disappeared four years later—possibly because a scope was too much added cost for shooters at that time.

Winchester built 355,363 Models 69, 69A and 697 from 1935 until discontinuing the 69A in 1963. The bulk were certainly the 69As, but how many purely Model 69s they made, I wasn’t able to ascertain. Winchester did not serial number these models; before the Gun Control Act of 1968, there was no requirement to do so, of course, but it sure would have helped us determine quantities and ages more precisely today if they had.

There are few affordable pristine examples of old-school hunt/competition crossover rifles, those that display pride of craftsmanship in the cut of their steel and wood, that please the critical eye and still perform as their makers intended at day one. I’m fortunate this one came into my hands.

And that is how an 80-year-old prom queen took my breath away.