"The volunteer force, without which NRA could not carry on the matches, contained many veterans of the 1968 and 1969 Perry seasons."

—American Rifleman, October, 1970

Some 400 strong, they converged on Camp Perry from California, Vermont and points in between.

Teenagers were there. So were housewives in their fifties and men up in their seventies.

Student, bank president, plumber, carpenter, retired colonel, and police officer—name an occupational group and you could find a representative at the matches.

These volunteers with their willing hands were wherever their services were needed—on the range or in the motor pool, swabbing floors, punching typewriters, running messages, fixing short circuits, or scanning Lake Erie to keep boats from straying into the impact zone.

Old Army man Frank Tillotson had headed up the carpenter shop with the Post Engineers at Fort Niagara, NY, for decades. He plied those skills at Perry. Craggy-chinned, blue eyes twinkling behind steel rims, Frank said he hadn't done any serious shooting until he was in his sixties.

"Bought me an A-3; went on the range one day with it and made 19 bulls and one four at 600 yards."

Frank admitted to being "seventy-five-and-a-half" and groused, "They ought to have a match for us old fellows over 75."

Like all other volunteers, Frank drew five dollars a day expense money at Perry. Like many of the volunteers he turned the check right back to the NRA—just as he did when he volunteered his services for the 1968 matches.

Nineteen-year-old Mike Ring, a walking showcase for his father's tattoo artistry, was honorably discharged on July 23 after two years in the Marines. Instead of making a beeline for his home in Colorado Springs, CO, Mike headed straight for Camp Perry for month-long service with a youthful mop-pail-and-broom brigade. Reporting to the NRA's Col. John K. Lee, Jr., USA (Ret), "Lee's Lost Legion" kept volunteers' quarters spotless and handled such miscellaneous assignments as scrounging a latch for a door or, in one instance, searching nearby Port Clinton for some moustache wax. Apparently it was good duty. Brian Pinkey, 16, of Tulsa, OK, back for his second year as a Perry volunteer, described it simply as "wonderful."

No volunteer at Perry fit easily into an "average" type and none less so than Bill "Big Red" Alexander, 60-year-old ex-teamster, ex-soldier of fortune, retired master sergeant, and a gunsmith in his North Canton, OH, home.

Admitting to a hearty loathing for the press, Bill was cagey about giving his reasons for leaving his gun business to contribute a month of his time, the use of his white Cadillac, and his own gas and oil expenses to the Perry motor pool.

A frown and a grinding of vocal gears:

"I was mad."

"At whom?"

Bill growled the name of a nationally known political figure.

"Come on, the real reason."

Much flexing of the Irish mug and inner mutterings and rumblings, then:

"I had nothing better to do."

Finally, grudgingly: "All right, all right, I came because I wanted to help out."

"Big Red's" better half also helped out. A retired WAC first sergeant, now a policewoman, Mrs. Mary Alexander established a special trophy, a .22 pistol, which was awarded to this year's Woman's Pistol Champion, Gertrude P. Schlernitzauer. Mrs. Alexander has invested her GI life insurance to perpetuate the award annually.

A fifty-ish widow and grandmother from Detroit, Mrs. Bernice McLonis charmed all who met her as she hustled through many household duties at the camp. She had volunteered "to do anything," and according to Col. Lee, left an indelible stamp on the premises. "She did the first real window washing job in the history of Camp Perry," he chuckled.

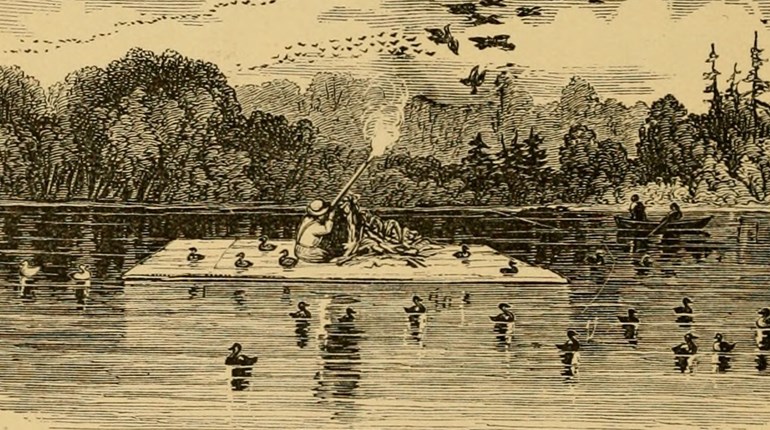

Nut-brown George Pinneo, 69, spent his days on the Perry watch tower maintaining contact with the boats patrolling the perimeter of the Lake Erie beaten zone. Pinneo had plied the trades of carpenter, builder, and lumberman in his native California and, in his watch tower assignment, swore he had "the best job at Perry." Had he been a competitive shooter? Pinneo shook his head. "I'm just a volunteer to help them put on the show. I'm a hunter."

Would he be back at Perry in 1970? The big man's tanned face was all grin. "I'll be back next year if I'm able. I know I'll be willing."

Coming to Perry was almost reflex action for Edgar Amos, 65. An NRA Life Member since 1929—"It's been so long it only cost me $50"—Ed first saw Perry in 1924 as a competitive shooter. Since then, "I've been coming back for years and years and years."

A retired electrician, Ed was "bumming around the country" by station wagon when he learned that volunteers were needed at Perry. Coming through Cincinnati, he ran into an old union buddy who offered him a job at $6.60 an hour. Ed passed it up, to work as electrical troubleshooter at Perry for $5 a day. He plans to go back to Perry early next summer "to find trouble before it happens."

Like Ed Amos, many volunteers had either shot competitively or had previous experience in the operation of shooting matches. But there were many like Joe Eichmeyer of Dayton, OH, Frank Tillotson's helper in the miscellaneous carpentry department. Joe, a hunter, finds competitive shooting "too dedicated a sport for me."

Why, then, did he spend his vacation working at Perry?

Joe suddenly suffered from the shyness which afflicted so many of the volunteers when this question was put to them. He shrugged, grinned sheepishly, finally got it out.

"I just thought I'd come out and try to help out a little bit," he said.

Those "little bits"—all those hardworking volunteers—more than 400 of them, added up to a lot. If you asked NRA Executive Director Louis F. Lucas, he'd tell you they made the 1969 NRA National Rifle and Pistol Championships possible.