“That mouse gun can’t shoot at 600 yards.” Such was our common dismissal of the M16 rifle back in the 1980s when our Navy shooting team was competing with Crane-built, double-lugged government M14s. It was true back then, and yet today the M14 has gone the way of the dodo and the M16/AR-15 rules the roost. How did the mouse gun pull off the coup? Rifling twist rate.

The earliest known rifling in a firearm barrel dates back more than 500 years, and possibly started as a few grooves cut straight down a barrel as an experiment to reduce black powder fouling in martial arms. Then someone discovered that twisting those grooves down the bore improved a rifle’s accuracy by imparting spin to the lead round ball. Further experiments found balls of different diameter demonstrated optimum accuracy when spun at different speeds. That speed is determined by projectile velocity and the rifling’s twist rate, an expression of how many inches of barrel is needed for the rifling to complete one 360-degree twist. We still use that expression today, such as 1:10, meaning one complete 360-degree twist per 10 inches of barrel, and verbalized as, “One in 10 twist.”

Twist rates were a trial-and-error matter until British mathematician Alfred Greenhill devised a formula in 1879 to accurately (for the time) predetermine it for elongated artillery projectiles, subsequently applying it to small arms bullets. In today’s digital info future, shooters can easily use Berger Bullets’ free (and more precise) online twist rate calculator to match optimum bullet weight to their barrel’s twist rate.

TWISTED FOR BATTLE

Casual shooters seldom consider rifling twist rate, because they don’t have to: firearm manufacturers typically rifle barrels with the proper twist rate for the heaviest bullets factory loaded in a specific cartridge. There is concern that a too-fast twist can “overstabilize” a lighter bullet or cause it to spin off its jacket, so more ammunition and bullet manufacturers are now including recommended twist rates on their packaging.

When the U.S. Army adopted Eugene Stoner’s AR-15 as its M16 battle rifle, the 5.56 mm NATO M193 loading was a 55-grain full metal jacket bullet stabilized with a 1:12-inch twist. Therein lay the yardage limitation of the M16 “mouse gun” as far as High Power Rifle competition was concerned, as 55-grain bullets are so susceptible to drifting in the wind at 600 yards that they couldn’t compete with the 173-grain bullets of the M14’s 7.62 mm NATO M118 Special Ball.

In 1967, the U.S. Army officially adopted the M16A1 (although the XM16E1 went to war in Vietnam in 1965, first with the U.S. Air Force), and immediately the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit began experimenting with accurizing the battle rifle for High Power Rifle competition. The U.S. Navy, too, experimented with the M16A1, at one point replacing the clumsy carry handle rear sight with a Redfield Olympic aperture sight.

Despite heavy barrels, lighter triggers, better sights, barrel weights, longer buttstocks and other improvements to the basic rifle, it was also obvious to everyone that 55-grain bullets were never going to cut the mustard at 600 yards. Heavier experimental bullets of 68 and 77 grains made an appearance, necessitating an increase in rifling twist rates—in the latter case, to 1:8. However, it wasn’t until 1983, after considerable experimental work by the U.S. Marine Corps to extend the effective range of the M16A1, that the resultant M16A2 got a 1:7-inch twist to accommodate the 62-grain bullets of 5.56 mm NATO M855 ammunition.

NO LIGHTWEIGHTS

It was that faster twist that finally made the M16/AR-15 competitive at 600 yards. As it so happens, that 1:7-inch twist also works across the competition board with the heavier 69-, 75-, 77- and 80-grain 5.56 mm NATO/.223 Remington bullets we shoot in High Power Service Rifles today. In a somewhat odd bit of logic, I have a handloader buddy loathe to “waste” 80-grain bullets at 200 and 300 yards, reserving them for 600-yard work and instead utilizing 69-grain bullets at closer range. For him, the 1:7-inch twist works at both the light and heavy end (though he must develop two different loads and keep the ammo clearly differentiated). Another shooter friend splits the difference, buying factory loaded 77-grain match ammo, and the 1:7-inch twist suits him, as well. Individual manufacturers have their own recommendations for matching their bullets and ammo to twist rates, and precision .223 caliber barrels can be had with twist rates as fast as 1:6.5-inch for those who want them for a comfortable margin in shooting .223 bullets weighing 90 grains.

.223 TWIST RATES

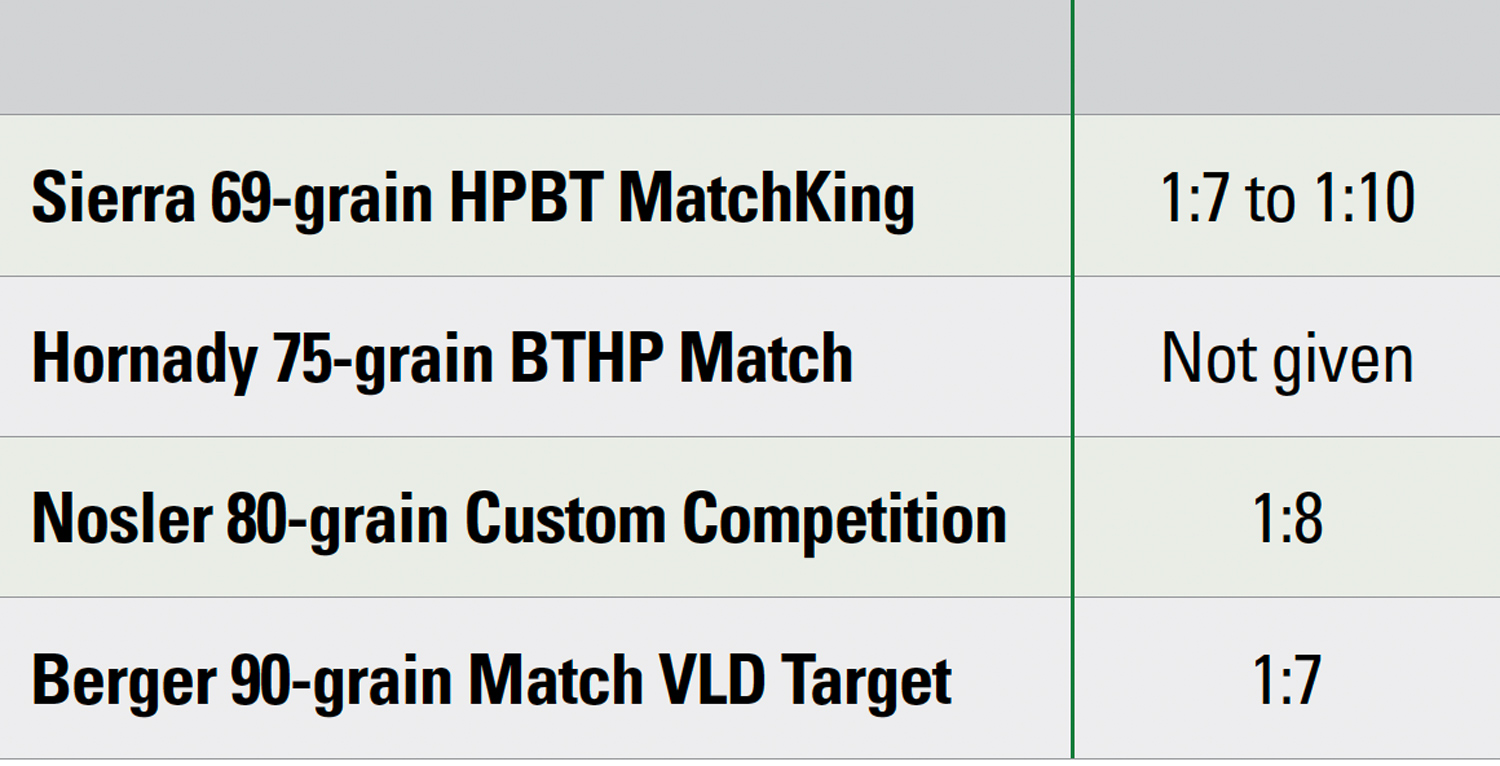

Here are manufacturer recommended twist rates for selected .223-inch bullets.

Might these faster twists deform or spin the jackets off of lighter bullets intended for 1:10-inch or 1:12-inch twists? Yes, but for the Service Rifle competition shooter, the practical answer is, “Who cares? I don’t shoot those lightweight bullets.” The same applies to any concerns or opinions regarding overstabilization due to a too-fast twist.

Every general issue U.S. battle rifle since the M1903 Springfield has been developed for precision shooting following President Theodore Roosevelt’s establishment of the Director of Civilian Marksmanship and national marksmanship competition in 1907. Though Stoner’s “mouse gun” had its share of teething problems, a change in twist rate changed it into the mouse that roared.