How well a suppressor works depends on who is testing it and what the shooter expects. A look at suppressor background, function and manufacturer claims can help when deciding on whether a suppressor is appropriate for your needs—and to avoid disappointment.

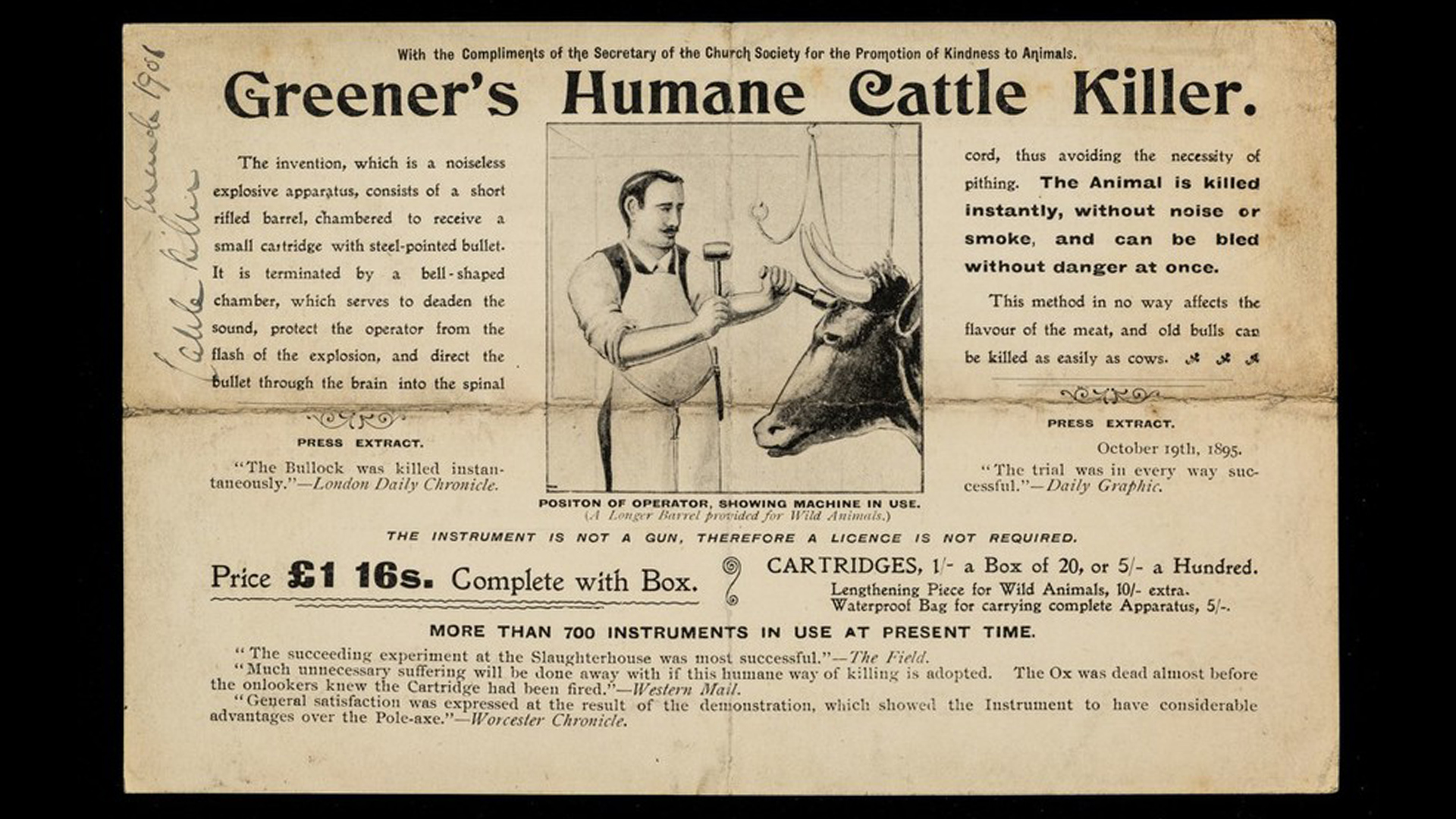

Few inventions spring up out of nowhere—they have precursors, just as the matchlock was a precursor to the M249 SAW and the Wright Flyer to the F-35. Today’s firearm suppressor is no exception, and it appears the first practical, commercially successful sort-of- suppressor dates to 1865 with the introduction of “Greener’s Humane Cattle-Killer” (note this date closely coincides with early successful metallic cartridges). The device was technically a kind of single-shot pistol, though you wouldn’t know it to look at it. In appearance, it was a straight tube with a bell-shaped chamber at the end. The “shooter” placed the bell end against the animal’s forehead and struck the back end of the tube with a mallet, which drove a firing pin forward to fire a cartridge, sending a .31 caliber bullet into the animal’s brain. A circa-1901 advertisement describes the instrument as “noiseless,” the bell end serving to “deaden the sound, protect the operator from the flash of the explosion and to direct the bullet through the brain into the spinal cord.”

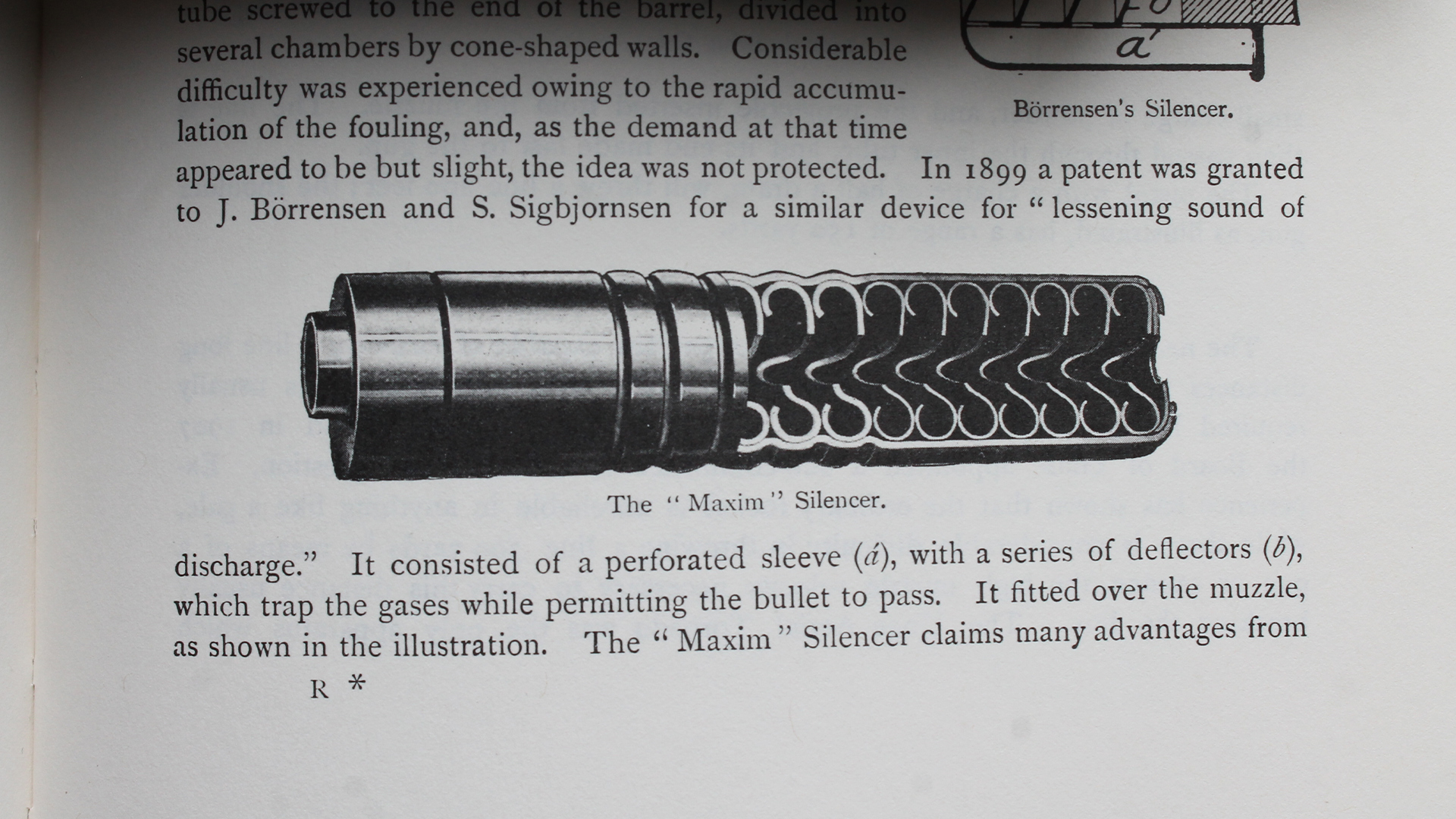

English gunmaker W. W. Greener wrote (“The Gun and its Development,” 1910, reprinted by NRA in 1995) that he experimented with developing a suppressor from the Cattle-Killer in the late 1800s, but the combination of fouling problems and low demand prompted him to abandon the project without seeking a patent. In 1899, J. Borrensen and S. Sigbjornsen received a patent for a device for “lessening the sound of discharge” of a firearm, which in appearance and function is much like a modern suppressor.

The earliest U.S. patent on a commercially successful device intended specifically to suppress the sound of a gunshot was awarded to Hiram Maxim for his “Maxim Silencer” in 1909. (This also appears to be why firearms suppressors are often referred to as “silencers,” although “Silencer” was the Maxim company’s own brand name for the suppressor. The British military referred to suppressors as “sound moderators.”) A print advertisement dating between 1909 and World War I extolling its suppressor notes in bold print, “The Maxim Silencer has been officially ADOPTED BY U.S.A. WAR DEPARTMENT.” Perhaps a bit disingenuous, the U.S. Army did dabble with suppressing its Model 1903 Springfield rifles, but abandoned the experiment about 1916.

In NRA’s October 1946 American Rifleman magazine, Maj. Gen. J.S. Hatcher reported, “Years ago, the Government experimented with silencers on the Springfield rifle and I happened to have a couple of these rifles with me when I was in charge of the Ordnance Depot and Machine Gun School in Harlingen, Texas, in 1916. The silencers reduced the recoil of the rifle considerably and completely silenced the report of the rifle itself. This fact served to call attention to the crack of the bullet, which had formerly been masked by the report. A weird effect was produced by firing one of these rifles along a railroad track, past a row of telegraph poles. The air wave from the bullet produced a sharp report as each pole was passed and the succession of reports sounded much like a burst from a machine gun. When this action became well understood, it was apparent that silencers could never be fully effective on a high-powered rifle and the issuance of silencers with Springfields was discontinued.”

Aside from his interesting anecdote, Gen. Hatcher points out that, though a suppressor effectively quiets the report of the gunshot (despite his comment, the report could not have been “completely silenced”), it can do nothing about suppressing the sound of a supersonic bullet passing through the air.

CRACK-THUMP AND CLICK-CLACK

Firearm suppressors work on the same principle as the exhaust muffler on your car, which is unsurprising, as Hiram Maxim also developed mufflers for internal combustion engines. The loud noise of a gunshot is the sound created by the expanding, high-pressure gasses of the fired cartridge exiting the muzzle at supersonic speed. Multiple expansion chambers inside a suppressor give the gasses room to expand, cool and decelerate below supersonic speed before exiting the front of the suppressor behind the bullet. The expansion chambers, however, have little impact on velocity; any bullet traveling in excess of roughly 1,125 f.p.s. (varying slightly with altitude and air temperature) is supersonic, creating its own shock wave that we hear as a loud “crack.” High Power Rifle competition shooters pulling targets in the pits hear first the crack of the bullet passing overhead, followed by the “thump” of the rifle’s report from the 600-yard line. We hear “crack-thump” because the bullet, traveling much faster than the speed of sound, and with its attendant shock wave, arrives over the pits before the slowpoke speed-of-sound gunshot can get there.

The recent plethora of subsonic ammo offerings is a direct result of so many states now permitting the use of suppressors for hunting, thus skyrocketing the suppressor’s popularity. Being subsonic, the bullet doesn’t “crack,” and when fired through a suppressor, there’s no thunderous gunshot report, either. The combination of a suppressor and subsonic .22 Long Rifle ammunition often results in the shooter clearly hearing the “click-clack” cycling of a semi-automatic action. In a suppressed bolt-action .22 LR rifle, I hear the click of the firing pin striking the cartridge. An added benefit is that a suppressor can also tame recoil and reduce muzzle flash. But as Gen. Hatcher implied, subsonic bullets aren’t an option in typical combat scenarios, as bullets must have high velocity to penetrate personnel and unarmored equipment, even at extended ranges where bullet velocity drops significantly.

STANDARD RATINGS

Sound intensity is measured in decibels (dB or dBA) with a decibel meter, so a suppressor’s effectiveness at suppressing the sound of a gunshot can be objectively evaluated. However, the different manufacturers measure suppressor performance using their own methods, and differing methods will produce different results, even with the same suppressor. Effectively comparing one suppressor’s design effectiveness to another requires identical methodology—that is, the same equipment and procedures must be used for testing both suppressors. Once methodology is agreed upon, then we can establish universal standards for rating suppressor performance.

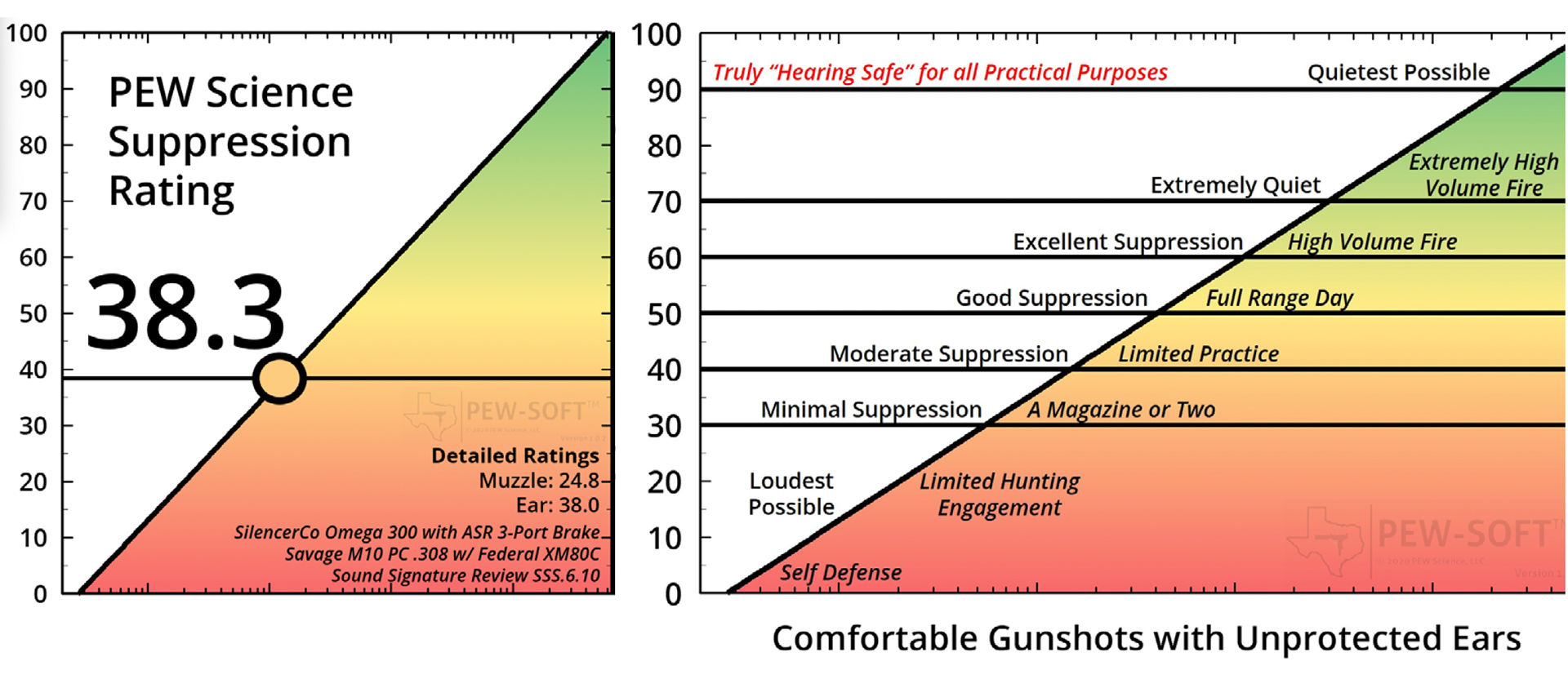

Somewhat like what SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute) does for cartridges and chambers, independent laboratory PEW Science is doing for suppressors. Standardizing test protocols for suppressors means manufacturers are all on the same page and buyers are comparing apples to apples in suppressor noise reduction performance. In the past I have participated in suppressor evaluations where we placed a decibel meter near the muzzle of the firearm and another near the shooter’s ear. PEW Science does basically the same thing, but goes much further than simply recording a decibel reading. PEW Science gets down into measuring sound speed in microseconds and pressure waves in micropascals with sophisticated detection equipment and software that render extremely detailed resolution. PEW Science places microphones in standardized positions, and all environmental conditions (especially with concern to reflecting sound waves) are taken into account.

PEW Science then objectively assigns a Suppressor Rating that runs from zero (loudest) to 100 (quietest). Ratings are assigned to a specific firearm and suppressor combination. The Suppressor Rating allows the buyer to shop for a suppressor based on his own needs; manufacturers can benefit from improved customer satisfaction, using the independent laboratory data toward improved designs, testing new designs and comparing their own suppressor’s performance against others’ suppressors.

SILENT JACKHAMMER

In the end, the question is, “How well does a suppressor suppress the sound of a gunshot?” Variables beyond the suppressor’s design include the type of ammunition, the firearm and barrel length, so there is no single inclusive answer for any individual suppressor. Typically, however, manufacturers claim a reduction of 20 to 40 decibels. Unsuppressed centerfire gunshots are in the 140-decibel range; a 40-decibel reduction puts that into about the same category as a jackhammer. Part of the reason a person perceives the suppressed firearm as quieter than a jackhammer is due to the extremely short duration of the sound of the gunshot compared to the continuous noise of the jackhammer.

And yes, using a suppressor intended for a large caliber rifle on a smaller caliber rifle—say, a suppressor designed for a .30 caliber rifle mounted on a .223 Remington rifle—will work, but some effectiveness may be lost. Subjectively, in my admittedly limited experience shooting suppressed firearms from .22 LR to .338 Lapua Magnum, virtually all suppressed centerfire firearms will still produce some level of obvious noise, even with subsonic ammunition, that can readily be heard many yards away. Only one firearm I’ve used, the aforementioned integrally suppressed .22 LR bolt-action rifle with subsonic ammunition, could qualify as being “silenced,” unheard by someone in the next room.

Which points up the fact that, “suppressor” is the more proper vernacular, rather than “silencer,” unless one cares to rate a jackhammer as “silent.”