Service rifle competition, part of the National Matches, has evolved over time incorporating each new-series service arm as it has been adopted, from the Krag, to the Springfield, to the M1, the M14 and now, the M16. Progress to the contrary, each new rifle has been greeted, with some greater or lesser skepticism by enthusiastic users of the previous arm. And, each new rifle has eventually surpassed its predecessor in scores and performance.

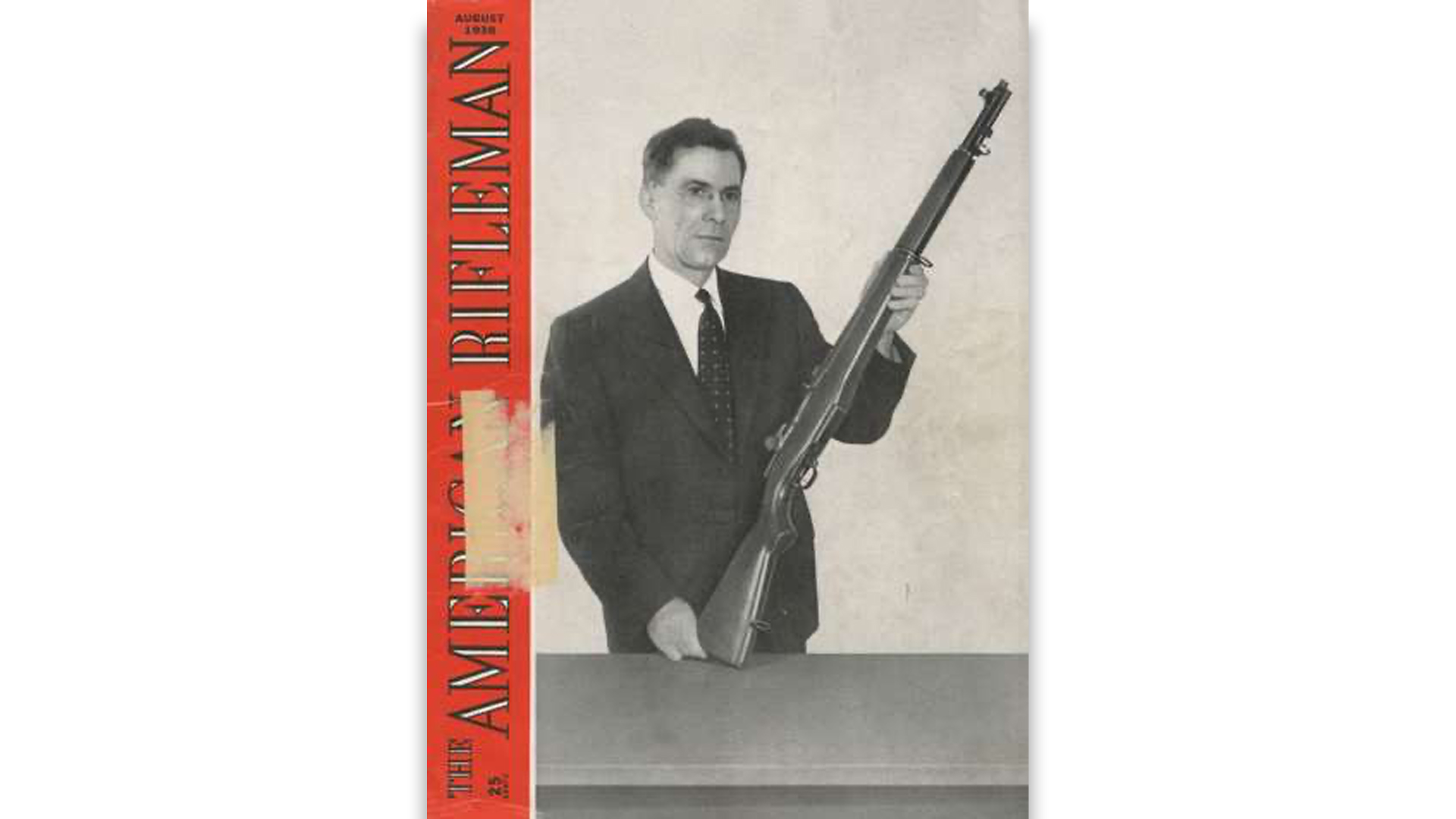

Thus it was, in 1940, the then-new U.S. Rifle, Cal. .30, M1 was introduced to civilians and to the competitive shooting world as part of the Small Arms Firing School (SAFS) conducted at the National Matches at Camp Perry, Ohio. Civilians at Camp Perry in 1940 could draw an M1 from the supply depot, learn about it in the school and then fire it in competition.

It is safe to say that a high degree of the “show me” spirit prevailed among civilian riflemen and military team members as well. The M1 rifle debuted at Camp Perry in 1939, just for purposes of a demonstration, and was not overwhelmingly accepted by those who first saw and shot it. Thus, the Army had good cause to worry about acceptance of its proud new rifle. As it began to enter service, the M1 developed several bugs, all of which required some sort of fix and which, taken together, made a statement more or less condemnatory of the Ordnance Corps selection process. (The M16 went through a similar rough introductory period, marked by misunderstanding of its capabilities and limitations. In the case of the M16, its premature introduction into combat cost lives, something that did not occur where the M1 was concerned.) Thus, it was that the Army was anxious for its new rifle’s introduction to the target range to be a successful one.

To begin with, the M1 was not the Model 1903 Springfield, and in the conservative world of riflemen that was important. The “03” was sleek, the product of craftsmen who put their hearts and hands into their work. The M1 was club-like by comparison and made by machine (the fact notwithstanding that the same “craftsmen” operated the machines. The “03” was the most accurate military rifle available. Experts had already called the accuracy of the M1 into question. The “03” was the rifle that won World War I and it was the rifle on which most high power rifle shooters of 1940 had learned their craft. The M1 was new and unproven.

The controversy surrounding the relative merits of the M1 and another self-loading military rifle developed by Melvin M. Johnson was also well known. Johnson’s contention was not that the M1 was inferior to his invention. He questioned the ability of American industry to produce John Garand’s design.

NRA’s then-Vice President, Maj. Gen. Milton Reckord—the Adjutant General of Maryland and a member of the National Board for the. Promotion of Rifle Practice, and The American Rifleman technical department chief, Fred Ness, had misgivings about the serviceability of the M1. Ness wrote a scathing critique of the M1 (sufficiently uncomplimentary to cause Charles Askins, Jr., to resign his NRA Life Membership in protest) that appeared in the May 1940 issue of The American Rifleman. Ness was not the only critical scribe. Walter McCallum, military correspondent for the Washington Star newspaper, questioned both the rifle’s effectiveness and the government's capacity to mass produce it. Both the Associated Press and Time magazine published articles critical of the M1.

Rumors (untrue) circulated that M2 Ball ammunition (a return to essentially World War I ammunition performance levels) was required because the M1 rifle would not stand up to the enhanced performance of more recently developed ammunition.

Both Ness and Reckord fell for this one. In fact, John Garand designed the M1 to operate using the more powerful ammunition that was standard issue after 1927. The M2 cartridge was loaded initially at the request of National Guard organizations that were losing places to shoot because the newer ammunition would shoot past the safety zones of most rifle ranges. (That, for what it’s worth, is what caused the closing of the old range up on District Heights —in Anacostia—where the D.C. National Guard used to train.)

Target shooters who fired the M1 as part of the 1939 Advanced Marksmanship School at Camp Perry complained about the oversize rear sight aperture.

Gen. Milton Reckord questioned both the utility and the durability of the gas takeoff system used to operate the M1’s self-loading mechanism.

One of the problems that plagued early M1s was the relatively fragile muzzle cap that diverted gas to operate the action. This weakness showed up in the earliest troop experience with the new rifle when bayonet training resulted in disabled rifles. A solution was devised and a modification of the gas system put into production beginning in October 1939. Rifles at Camp Perry in 1939 had the old “gas trap” system. Rifles having the now-familiar gas cylinder and ported barrel began to reach users in May 1940, and must have been sent to Camp Perry for the 1940 National Matches.

A second mechanical problem was worse. Solving it, or at least overcoming its immediate consequences, needed drastic measures.

The M1 rifle and its eight-shot, en bloc ammunition clip were designed so that ammunition makers did not have to worry, when inserting cartridges into the clips, whether the top cartridge was on the left or right side of the clip. But, in practice, if the top round was on the right, the seventh round would fail to chamber, instead stubbing the bullet point against the receiver at the rear of the barrel. Soldiers, equipped with the M1, simply made sure that ammunition was clipped with the top cartridge on the left, but for Camp Perry this would not provide the whole solution. Springfield Armory sent Gen. Julian Hatcher’s brother, James Hatcher, to Camp Perry to make sure that everything went well. Hatcher developed a modified magazine part that would only accept a clip with the top round on the left. Then he had the armory fabricate a supply of these parts and installed them in the rifles sent for demonstration. Finally, he and a detail of soldiers examined every clip of ammunition sent for M1 rifle use, and made sure that all of them had the top round loaded correctly. The 1939 demonstration went off without a hitch, and by 1940 the cause of the problem had been found and solved.

In the course of the 1940 National Matches, four contests were fired using the M1. All were devised to point up the advantage of the M1’s self-loading action and eight-shot magazine capacity. The first was 16 shots, fired sitting or kneeling from standing (sitting rapid fire) in 60 seconds at 200 yards range. The second was 16 shots prone rapid fire from 300 yards, within 80 seconds. The standard “A” target was used for both the rapid-fire matches—a 12-inch diameter black aiming bull, valued at five points without the customary tie-breaking “V” ring. The third contest was known as the Instructors’ Match, or the Surprise Fire Event. Surprise Fire was a 16-shot match, fired standing, at targets that were raised from the pits for a short interval, then pulled back down. Two shots were to be fired at each exposure. Distance was 200 yards. For the Surprise Fire match, the “B” target was used. Normally shot at from 500 and 600 yards, the “B” target had a 20-inch diameter, five-point bullseye and a 12-inch V-ring.

Civilians won two of these three matches. C.L. Swett, of the Nevada team, fired an 80-point possible score in the sitting rapid-fire match. Swett’s was the only clean score posted. Sgt. Steve Disco of the Marines and Sgt. Robert Brown of the Infantry posted the second and third place scores.

At 300 yards, the U.S. Army’s Infantry Branch team members took the honors, though it needed a tie-breaking shoot-off to decide the matter. Cpl. Carl Byas racked up a 77 in the match and bested shoot-off efforts by second place winner George Johnson, of the Massachusetts civilian team and another Infantryman, Sgt. Wadie Giacobbe, who finished third.

Surprise Fire went to civilians. A.D. Siedschlew of South Dakota topped the field with a 74-6V. Wallie Burnham of Montana carded a second place 74-4V. In addition, William S. Brophy of the New York civilian team took third at 71-6V.

The final event, reserved especially for the M1, was a 10-person team match, slow fire prone at 600 yards range. The course of fire is listed in both the program and in match reports as being for eight shots per firing member. However, the winning score was such that each firing member must have fired 10 shots. It took the U.S. Marine Reserve team a 467 to eclipse the regular Marines’ second place effort (by a point) and the 461 scored by the third place North Dakota civilian team. Noteworthy are the facts that a reserve component team beat a regular team in the first team match ever fired with the M1; that one of the reserve team members was First Lt. Emmet O. “Doc” Swanson, NRA’s president in 1948, and that another Marine, Col. Walter R. Walsh (then a Marine Reserve, First Lt.) shot on that team and remembers well his introduction to the M1, and the victory over the regular Marines.

The sum and substance is that the Army must have been pleased with the results of the M1’s National Matches debut.

Changing the gas system apparently took care of objections concerning the rifle’s tendency to change zero as it got warm (as is shown by scores in the 600-yard team match), as well as reservations about durability. They changed the rear sight, too, in that 1939-1940 time frame, going to a locking bar to hold the elevation adjustment in place. The seventh round jam was solved when someone noticed that production engineers had adopted a shortcut that changed John Garand’s original magazine design. Doing away with the shortcut did away with the problem.

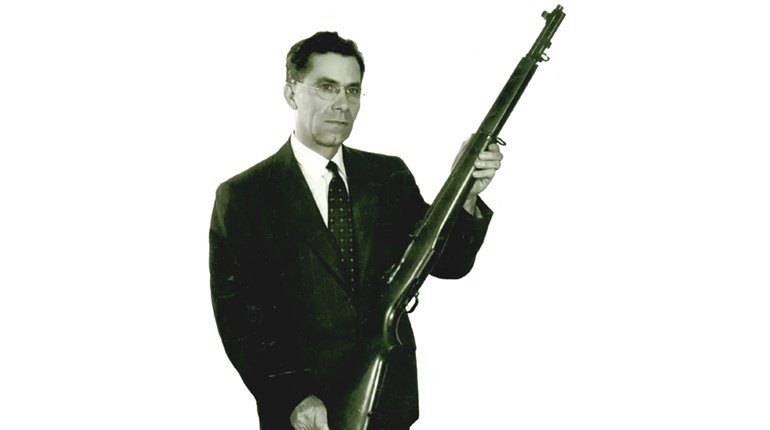

It is interesting to note that no one ever really credited John Garand’s ability as a tool designer. He developed the M1 as part (the end result) of a combination of tooling and design techniques. When the “experts” did things the way Garand set them up, his rifle worked just fine. Whenever anyone tried to improve on his procedures, things went awry. The same is true of the capacity to make lots and lots of M1s, quickly. Relatively unhurried (before Pearl Harbor), Springfield Armory took its time building its production rate to approximately 600 rifles per day (against an initial order for 240,000) in January 1941. By September 1943, under wartime conditions, Springfield got the production rate up to 100,000 rifles per month—4,000 per day. And they used the tooling and production flow plans drawn up by John C. Garand to reach those levels.