“Thus the serious work of the National Matches has gone on for nearly a decade; and thus it will go on for decades longer, establishing upon a firm foundation that essentially American tradition and intensely practical national bulwark—the art of straight shooting.”

—The American Rifleman, September 1924

The 1924 National Matches marked the 12th time that the event was held at Camp Perry and the sixth time that Lt. Col. Morton Mumma served in the capacity of Executive Officer. But that is where any sense of the familiar ended, for unlike prior National Match competitions, this year’s results bulletin was the most balanced to date. No one organization or service team dominated the field.

In a reversal of recent government practice, the funding of civilian and National Guard teams to attend the National Matches was reinstated in 1924, although some civilians had already made the decision not to attend by the time the announcement was made. The Secretary of War authorized the expenditure on August 9, less than a month before the start of the Small Arms Firing School, which included training on range operation. Lower civilian participation around this time might also be linked to lingering repercussions from when many state associations had gone dormant during World War I.

“The holding of the National Matches themselves is very largely due to the favorable sentiment which the National Rifle Association has succeeded in creating among the public in general and among Government officials and legislators toward rifle practice.”

—1924 National Match program

With the federal money that was provided, it was obvious that through enforcement of National Team Match elimination rules, the Congressional intent was to invest National Match funds on the propagation of new shooters. Under the 1924 ruling, at least 50 percent of service team members (Class A) had to be new to the National Match Rifle Team, while requirements for new shooters in the other classes were not as strict, and ROTC and Civilian Military Training Camps (CMC) shooters were exempt from the ruling altogether. And the policy whereby returning shooters were limited in the number of consecutive years they could compete helped ensure the turnover in team makeup that the government sought in order to direct its funds to a wider audience.

“… to permit lack of government funds to keep a team at home is a sad commentary on rifle sportsmanship.”

—The American Rifleman, October 1924

This year’s NRA matches were the largest to date despite concerns about an outbreak of smallpox. Subsequently, competitors were required to submit proof of vaccination as a precaution and anyone not able to do so was forced to leave camp or be treated on site. The American Rifleman also reported that “the vaccination of shooters in camp has its lighter side, and there were many limping to the firing line this year assuming the sitting position with groans and lamentations. During the first week of the camp, more than 400 shooters received treatment.”

Once the shooting got underway, shooters were offered a number of new events, the most novel being the Chemical Warfare Match, won by the Navy’s Lt. Van Rathbun. Other highlights included the steady increase of smallbore activity which, like the year before, took place on ranges in the center of camp with the longer events fired on the main 200-yard range. Until now it was not unusual for the .22-caliber game to be shot on makeshift ranges in order to accommodate other demands of the match program. But despite this nomadic existence, the number of entries mushroomed, so much so that a smallbore committee was appointed in 1924 to address the development of this popular sport. Not surprisingly, one of the committees first recommendations was to establish a permanent smallbore range. The committee also reviewed the issue of not squadding single-entry matches. The opinion was that, as smallbore entries increased, assigned relay times should be employed in the same manner that the service matches were conducted in order to maximize range capacity and eliminate the element of gauging shooting conditions. Much had been done in other areas to encourage more shooters to attend the smallbore matches, including print publicity and the addition of a special Smallbore Expert Rifle Marksmanship Medal Match, whereby a minimum qualifying score fired at one or more distances with metallic sights earned the shooter a medal that indicated the demonstrated level of proficiency.

Pistol competition continued to grow, and in 1924 the free pistol was introduced to the program in the slow-fire 50-yard matches. The popularity of handgun shooting was also evident in the police matches, where a new individual match and an exhibition on quick draw technique, or “snap shooting,” took place, in addition to a record 10 entries in the team event. A National Match course of fire change was also implemented this year when the 50-yard slow-fire stage, shot after the timed- and rapid-fire stages the previous two years, started off the competition this year, just as it did in 1920 when the National Trophy Team Pistol Match was introduced.

Among the NRA big-bore team events, the Herrick Trophy Match produced one of the program’s highlights when the Coast Artillery edged the Marine Corps by four points in a match that was decided on the last shot. And what was considered to be even more of a surprising finish took place in the Infantry Match, where the Oregon National Guard knocked the Infantry from the first place perch it had held since the match originated two years earlier.

“There was more special equipment on the line at Camp Perry this year than ever, and many of those who did drift in with the idea that the Springfield ‘as issued’ was good enough for them, succumbed to the line of the ‘tailor made rifle.’”

—The American Rifleman, October 1924

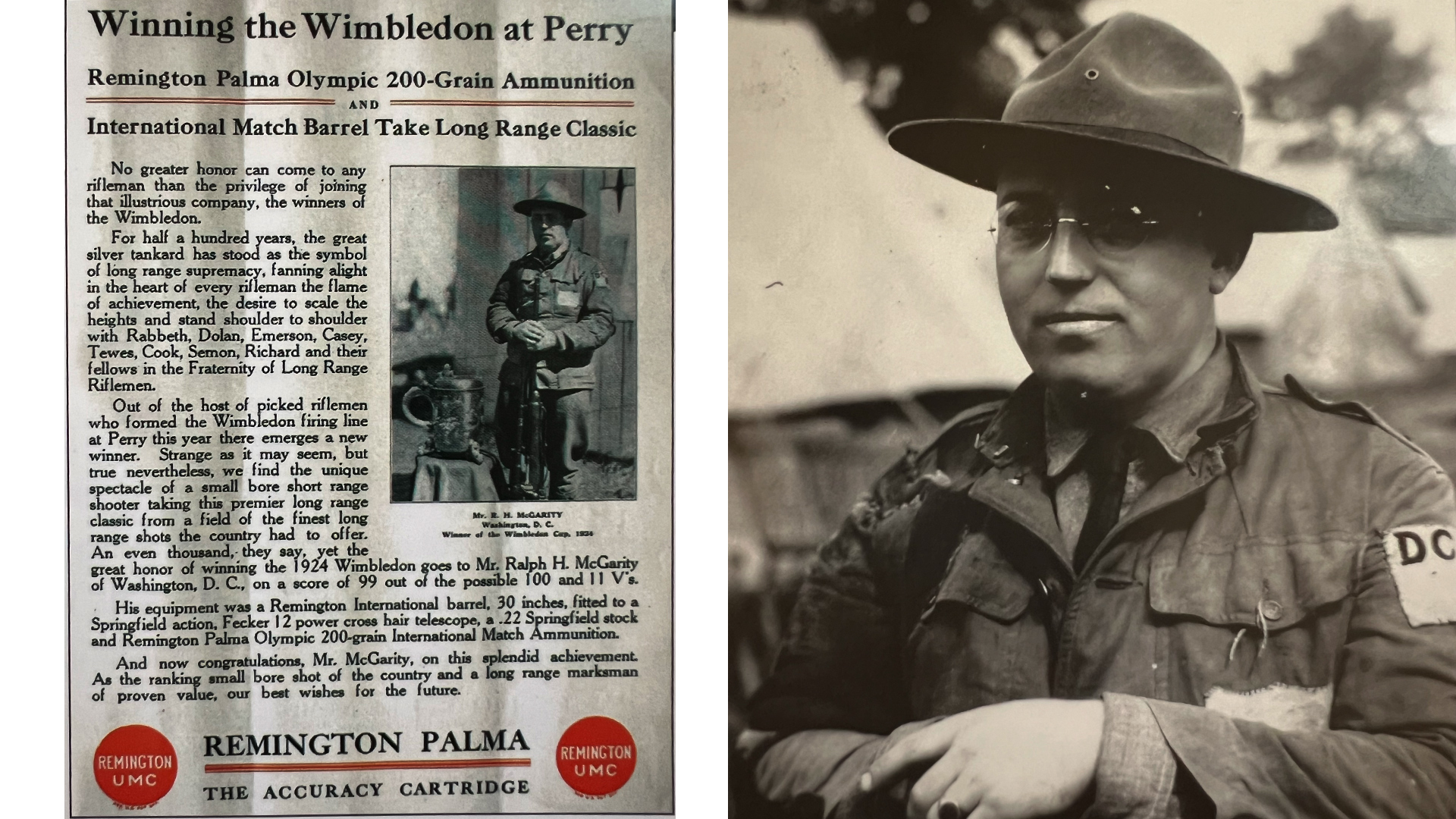

The popular Leech, President’s and Wimbledon Matches were won by Lt. Paul Martin of the Cavalry, Lt. Louis Jones of the Infantry and Ralph McGarity of Washington, D.C., respectively. The Leech and President’s Matches each fielded more than 1,000 shooters, while McGarity’s win was tops among the 999 entries in the Wimbledon and marked the first time since 1921 that a score less than 100 took the prize. Interestingly, McGarity won with a scoped rifle that he borrowed the night before—a 30-inch Remington International heavy barrel mounted in a .22-caliber Springfield stock of which he hacked half an inch off the butt. McGarity’s win followed an impressive accomplishment on the smallbore range a few days earlier, where the 1923 national smallbore champion recorded 125 consecutive bullseyes at 200 yards in a re-entry match—a performance that was permitted to continue beyond the cease fire call in order to finish the record run.

The 1924 national smallbore title went to Francis Parker of Illinois with a 247 out of a 250 possible after his long-range score served as the decisive tie-break over Lt. A.M. Siler of the Infantry. And the Dewar team, under the direction of Grosvenor Wotkyns, assembled in a driving rainstorm to do battle. As rain quickly filled the aperture sights, the decision to delay the competition was made, since several days remained until the match had to be fired. Since the program was conducted later in the year than usual, it was not until September 29, 1924, that the Dewar Match took place.

By that time the rain had stopped, but the temperature dropped considerably and shooters were faced with the possibility of snow as they faced a stiff, cold wind off Lake Erie. The match could not be postponed any longer and Wotkyns knew the key to success was good coaching. With only 10 coaches on hand, he opted to divide the team into two relays so each shooter had his own coach. The team fired U.S. equipment exclusively for the first time: 11 Winchester 52s, seven Springfields and two custom rifles built on Ballard and Martini actions. The result was a score of 7779, which was 23 points better than the British and meant the Dewar Trophy stayed in the United States for another year.

“Lake Erie weather gods are practical jokers ... three days of rain pelted on the camp … and the mercury shivered down in the thermometers to the lowest point possible without a freeze ... just as everybody was becoming resigned to the mud, the wet and the cold, the skies cleared and Camp Perry was at its best.”

—The American Rifleman, October 1924

Lt. Col. George Shaw was named DCM Director this year and according to the War Department’s organizational structure, also assumed Executive Officer duties of the National Board. Among the Board events this year, the National Rifle Team Match did not disappoint. Rather, it injected a sense of hope into the minds of those who may otherwise have thought that results in the service category were all but predetermined.

As reported in The American Rifleman, “Each year when the giants of rifledom join issue to decide the National Match Championship there is the ever-present possibility—far-fetched and seldom realized—that a dark horse team will finish in the fore. That is what happened at Camp Perry on October 2, when the Army Engineers nosed out the Marines ... And all the more credit is due to the Engineers because to all intents and purposes it is a new outfit. This is the first year it has been independently from under the wing of its foster father the Cavalry.”

In addition to the presentation of the National, Hilton and Soldier of Marathon trophies this year in the rifle team match, the fourth, unnamed trophy returned after a three-year hiatus when a class for Organized Reserve shooters was added to all four National Match events.

In the National Pistol Team Match, the Infantry finished first among the 23 entries, only 20 of which actually fired. Nevertheless, the turnout was much larger than expected and match officials telegraphed headquarters for more medals to accommodate the expanded field.

In the individual Board events, Marine Capt. William Ashurst won the rifle title and Lt. Raymond Vermette of the Infantry earned the pistol title. Both posted high overall scores in a year that marked the first time awards were presented in regular service, National Guard, Organized Reserve and civilian categories. The 1924 National Matches also marked the first time that trophies were awarded to both individual winners, as previous prize policies involved the presentation of gold medals to the top 12 scorers.

“No rifleman’s education is complete without National Match experience, and no rifleman has attended the matches at Camp Perry without immediately starting to lay plans for his return the following year.”

—1924 National Match program

1924 National Matches Fact

The date June 7, 1924, was earmarked “National Rifle Day” on ranges across the country which were open to the public. As a special promotion, some cities offered financing of one junior to the National Matches.