The year was 1921. The place—Lyon, France. The occasion was the nineteenth World Shooting Championships at 300 meters. Until then, the U.S. team had never fired on a baffled, enclosed safety range, but they were firing on one now and they weren’t enjoying it. On August 9, the five-man Swiss team had defeated the U.S. in the standing match (40 shots per man) by 47 points. The next day, the Swiss had beaten the U.S. kneeling score by 18, leaving the USA trailing the Swiss by 65 points going into the last day’s shooting. The last day would entail 40 shots in the prone position.

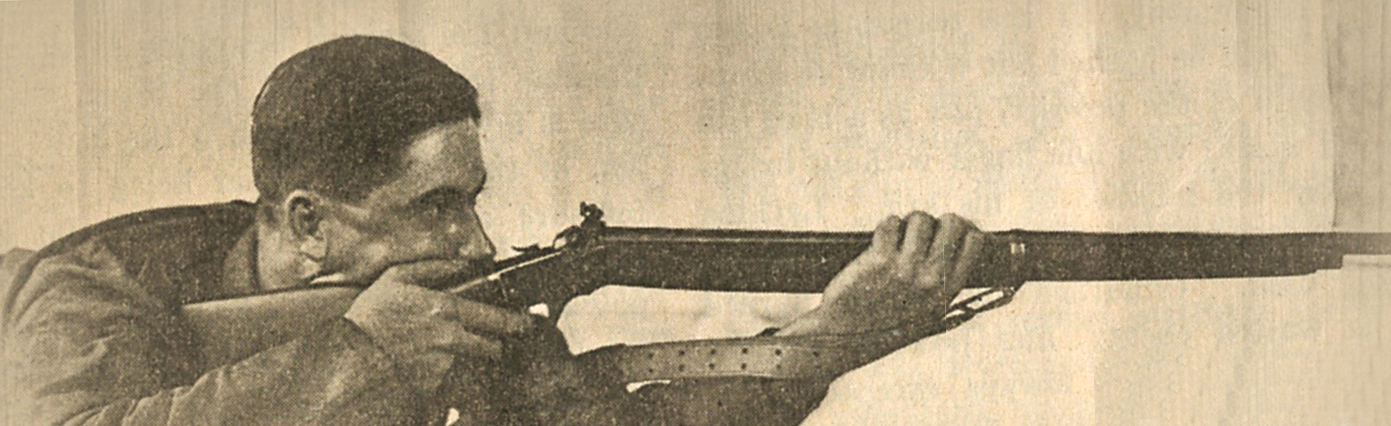

All the news was not bad though. A 23-year-old civilian from Washington, D.C., named Walter Stokes had won both the standing and kneeling World Championships, in both cases defeating the Swiss hard-holder—Hartman.

The scores counted for both team and individual World Championships under the rules of the International Shooting Union (now known as the International Shooting Sport Federation, ISSF). Nevertheless, the outlook for the Yanks was grim. Unappreciated by the Europeans was that the Americans had secret weapons, passed on and approved as legal by the match officials. These “secret weapons” were the rifle sling, aperture rear sights and, as it turned out, Walter Stokes.

The use of the rifle sling as an aid to shooting (rather than as a carrying device) was arguably invented by, and certainly promoted by then Lt. Townsend Whelen in his 1906 book Suggestions to Military Riflemen. Strange as it may seem, neither the sling (as support) nor aperture sights were commonly used in European rifle competition in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Although we expected that our equipment (slings and sights) would be deemed legal on match day, we had a “hole card”: each rifle was drilled and tapped to mount the Model 1902 Krag rear sight, which is an open sight, adjustable for windage and elevation.

The ten rifles (in three different stock configurations) had been assembled in a “hurry-up” basis by Springfield Armory and issued to the team, which took them to the nearby Wakefield range for a few familiarization rounds. It is astonishing, today, that the team would be issued their match rifles just days before departure, but they were all familiar with the Model 1903 Springfield and these match guns were, basically, carefully fitted and “gussied-up” M1903s.

Because of time constraints, the team itself was not selected by a try-out, but by “…an arbitrary selection of team personnel from the ranks of the best shots available…” (Arms and the Man, LXVII (24) August 1, 1921). The team included the legendary Morris Fischer as well as Lt. Cdr. Carl Osburn, USN, who would ultimately accumulate eleven Olympic medals in shooting—more than anyone else, in the years 1912-1924.

When the prone match got under way on August 11, 1921, the advantages of slings and aperture sights quickly became apparent. Shot by shot the U.S. team gained on the Swiss. By noon, the Americans had erased the 65-point deficit and taken a two-point lead. When the match was over, USA was ahead by 82 points in the aggregate of the five individual three position scores. We had beaten the Swiss in prone shooting by 147 points, almost 30 points per man, and had defeated the Europeans at their own game. To make it worse, the Americans had shot the top three prone scores. We were unequivocally World Champions at 300 meters. The Swiss were understandably annoyed. In the preceding eighteen World Championships, they had won seventeen, losing only to the French at Turin, Italy in 1898. There was some serious grousing and grumbling about “special technical equipment” used by the U.S. team, but everything had been pronounced legal and approved. Grumbling notwithstanding, the precedent had been established, and the utility of the newfangled gear had been demonstrated.

To add some very important frosting to the cake, Walter Stokes had also won the prone match, thus becoming a four-fold World Champion (standing, kneeling, prone and aggregate) at 300 meters. His scores were respectively, 326, 357, 372 and 1,055. Only the great Swiss marksman Konrad Staheli had won all four 300 meter World Championships in one year (in Rome, in 1911) and no one from any nation has done it since.

Since 1990, the ISSF no longer awards World Championships in each of the three positions. Therefore Stokes’s feat, under present rules, cannot be repeated. Slings and aperture rear sights quickly became invariable features of international rifle shooting and, I think it is fair to say, changed the sport forever.

Walter Stokes continued shooting internationally and nationally, winning, among much else, the 300 meter three position world title again in 1922. He remained an active competitor into the 1930s and maintained a medical practice as a psychiatrist in Washington, D.C., until 1963. But that is another story.