Operation of a semi-automatic pistol is a finely tuned process. Rounds have to feed reliably from the magazine, and when fired, the brass is extracted from the chamber and ejected out of the gun. Ejecting spent cases seems simple and straightforward. As the slide moves rearward from the force of recoil, the ejector kicks the brass out of the gun to make way for the next round. Ideally, the brass ejects to the side and away from you.

However, sometimes ejection is not perfect. The case can hit the inside of the slide and bounce back into the ejection port, causing a malfunction. On occasion, the ejected case will angle straight up and come back toward the shooter. Hot brass flying towards your face (or down your shirt) will be followed by a strong, reflex action that is generally accompanied by harsh language.

My Smith & Wesson M&P45 2.0 compact pistol is an ejection problem child. It throws brass straight up and back, and it’s not just the occasional round, either. Most are thrown over me, but some—especially light loads—were hitting me. Some even head directly towards my face.

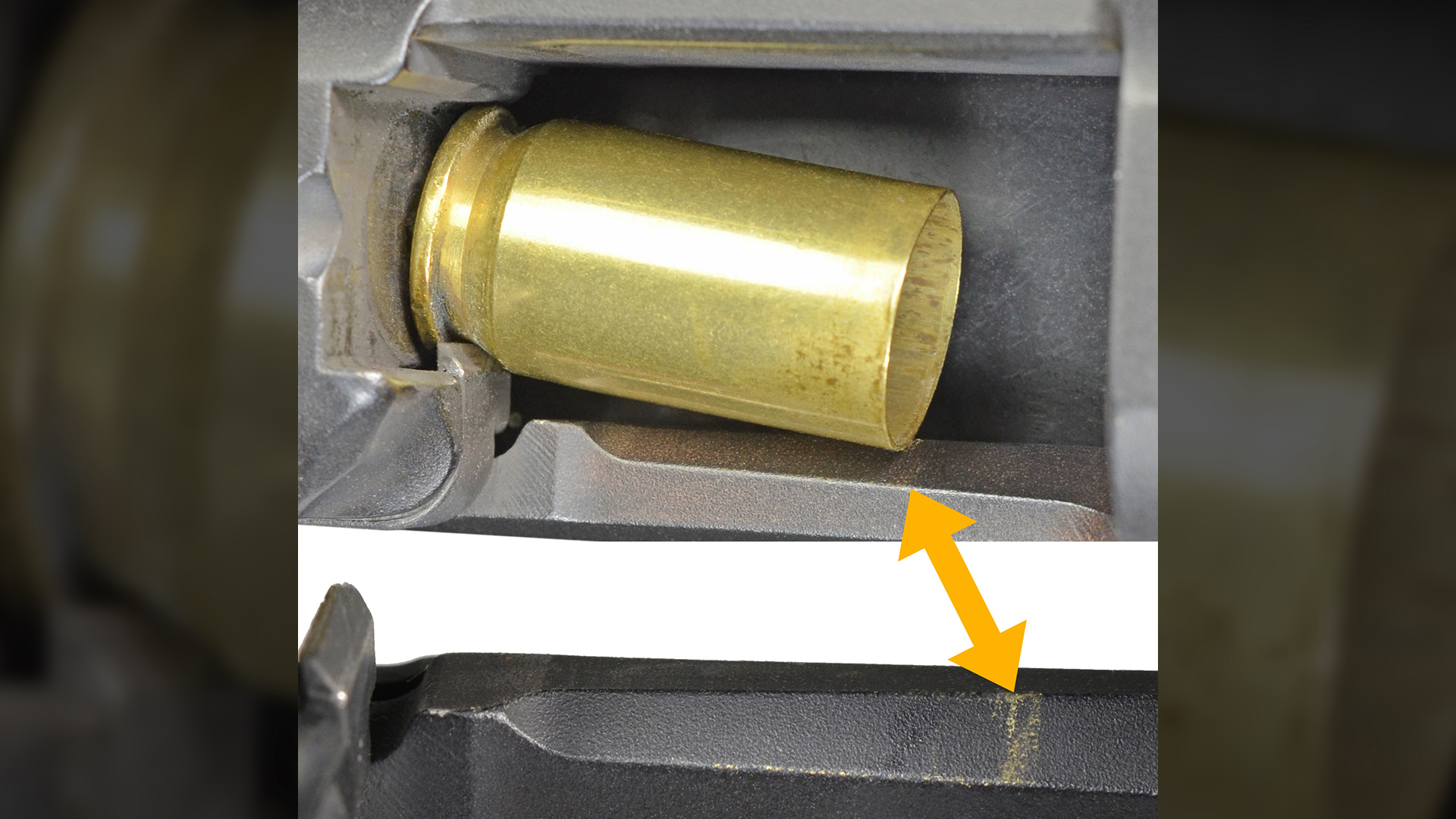

One might think the ejector was hitting the brass too low and close to the center. That could direct them straight back. But that wasn’t the case. In fact, the ejector was kicking them laterally, but at too low of an angle. The brass was hitting the inside of the lower edge of the ejection port, and this was causing them to bounce straight up. Evidence of this is a brass-colored mark on the ejection port wall.

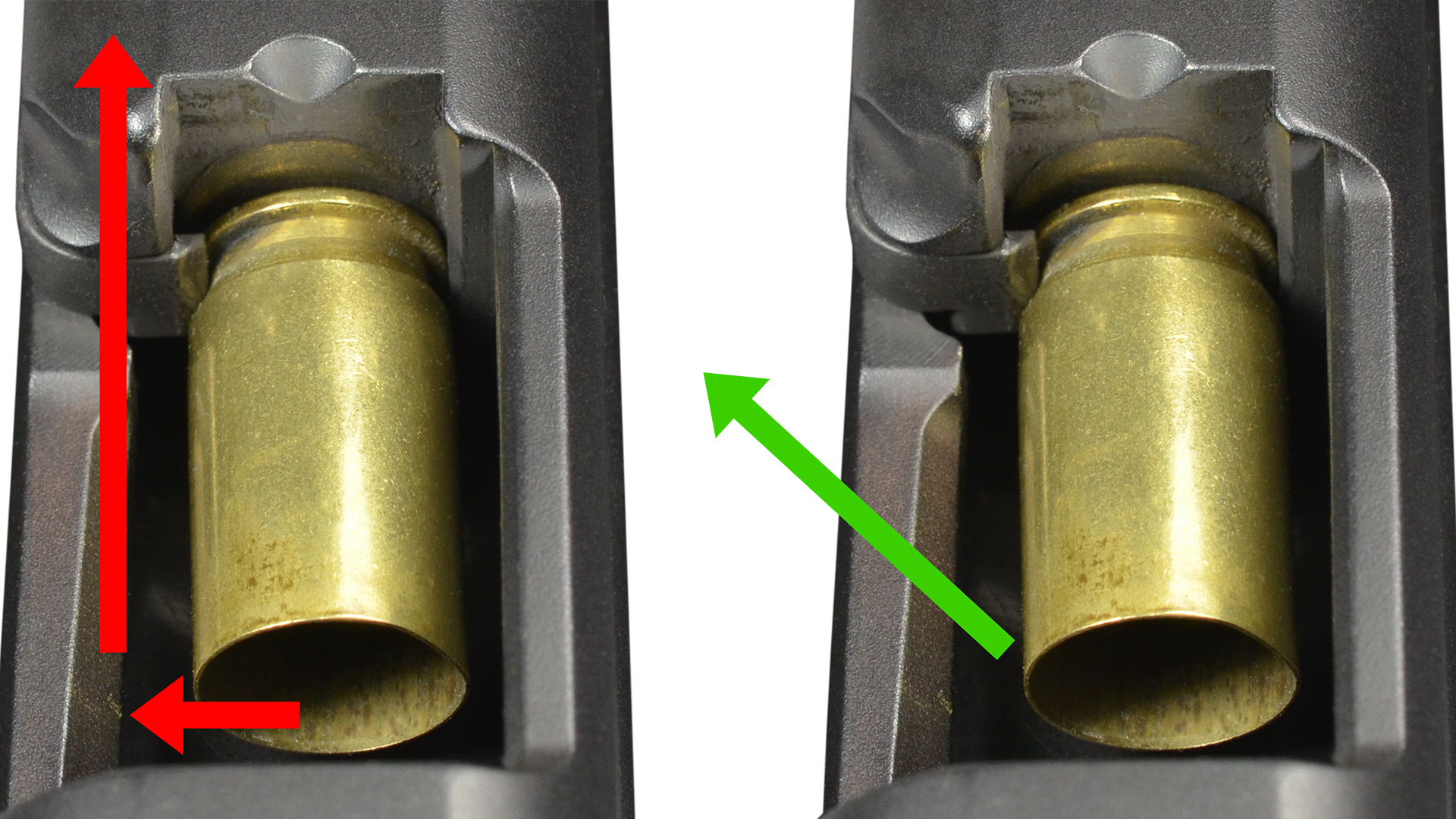

How do you make the brass eject at a higher angle to avoid the slide wall? One way is to make the ejector contact the brass at a lower point. This will cause the brass to be angled upward more, and lateral trajectory at this higher angle means that it won’t hit the inside wall of the ejection port.

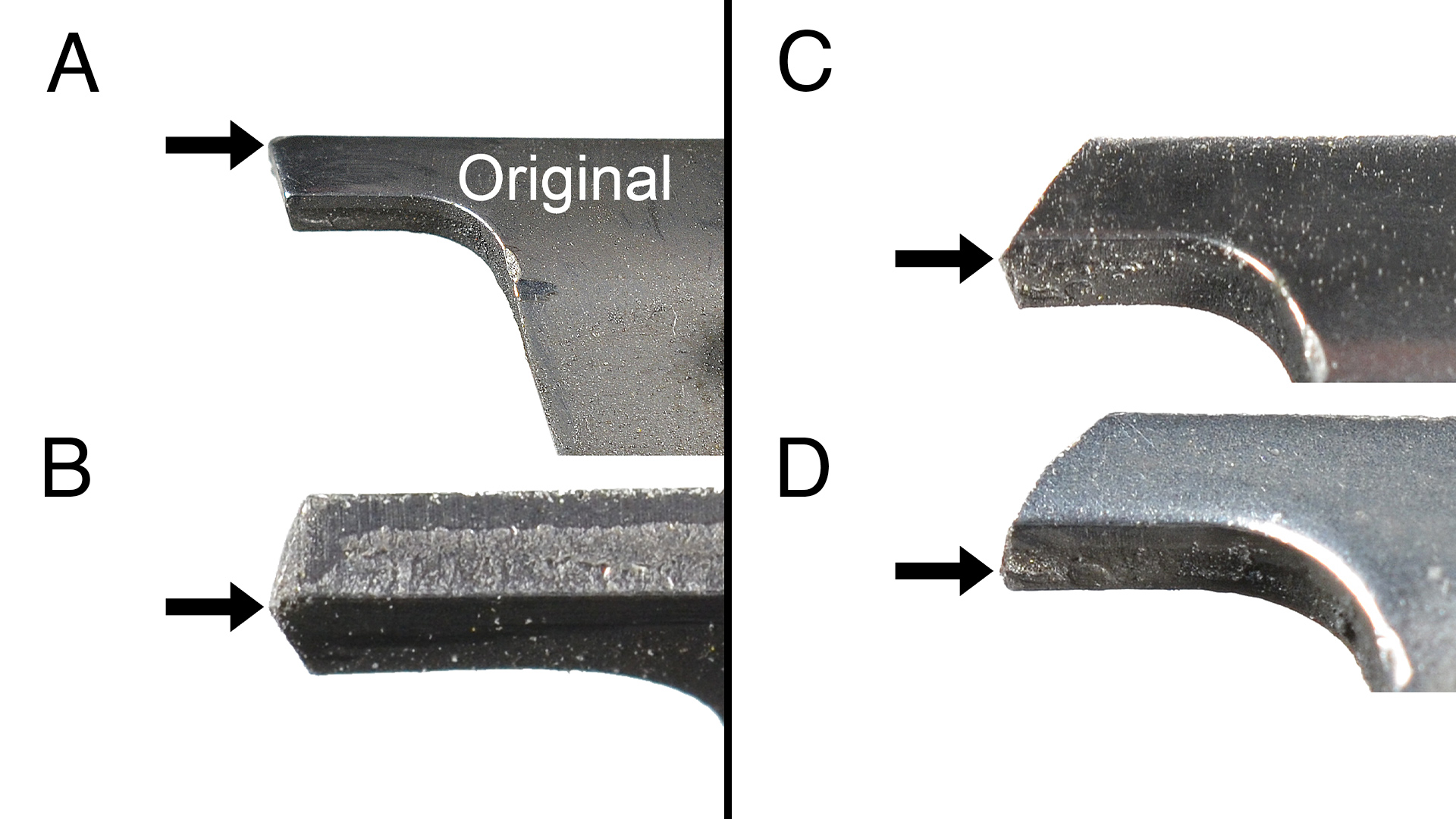

The contact point of my M&P45 2.0’s ejector nose was at the top of the ejector. This means I can move the contact point lower by beveling the top of the ejector nose.

I used a diamond file to lower the ejector’s contact point. I first cut down about halfway of the ejector nose height, moving the contact point near the middle of the ejector nose. This resulted in about 80 percent of the cases ejecting correctly to the right. But some were still being launched straight up over me. Examination of the inside of the ejection port wall showed there was still a brass mark, additional evidence that some brass was still being deflected straight up.

Next, I lowered the contact point even more, down to about 75 percent of the original ejector height. Thirty-nine of 40 rounds (97.5 percent) ejected right. This showed improvement, but the goal is 100 percent.

My third cut lowered the contact point to about 90 percent of its original height, which fixed the problem. Right ejection was 100 percent out of 180 rounds fired—ejection perfection.

Given how close the 75 percent cut was to ejection perfection, I probably didn’t need to move the contact point all the way down to 90 percent and could have achieved my goal at 80 to 85 percent. Nevertheless, ejection is perfect in its present state.

This example demonstrates how moving the contact point on the ejector can change how the spent cases are ejected from the gun. Moving the contact point lower on the case will force brass to eject at a higher angle in a way they don’t hit the slide wall, and eject at the proper angle to the right—away from the shooter.

If your pistol is tossing brass back at you, look for the brass-colored mark on the inside wall of your ejection port. If it’s there, this is a sign the brass is being deflected off the ejection port wall. You might be able to fix it yourself, or maybe talk with a competent gunsmith. A little file work can do wonders for changing ejection angle.