WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

Dry firing is one thing, but target shooting in one’s living room would certainly be considered alarming today. Yet in the past there were guns and ammunition specifically intended for the pursuit. The ammo is still around, and if you fancy to revive the sport, throwback parlor guns like this one can be had—but there are caveats.

Perhaps the best-known example of shooting in one’s parlor is the fictional Sherlock Holmes, who would practice with his revolver in his Baker Street apartment and which his landlady, Mrs. Hudson, apparently tolerated as not-especially-eccentric. Presented here is a “Flobert gun,” also known as a parlor gun, saloon gun and in America as a gallery gun. Such rifles and pistols were popular for indoor shooting until the early 20th century. In America, they continued on for a time as “gallery guns,” pump-action rifles firing .22 Short cartridges at fairs and carnivals.

Flobert Cartridges and Guns

Louis-Nicolas Flobert placed a lead ball atop a percussion cap in 1845 to make, arguably, the first successful self-contained metallic cartridge which, with due humility, he dubbed the 6 mm Flobert “Bulleted Breech Cap.” That same cartridge bears the American acronym .22 BB Cap and was followed by the somewhat more powerful conical breech cap, the .22 CB Cap, around 1888. All incarnations are sans powder, driving their lightweight 18-grain bullets with only the primer charge. Smith & Wesson soon picked up on Flobert’s idea to create, again just as arguably, the first commercially successful metallic cartridge, the .22 Short, in 1852.

Flobert also made guns for shooting his 6 mm Flobert cartridges indoors, hence “Flobert guns.” Other manufacturers followed suit but, of course, could not use Flobert’s name, so we have the alternate names of “saloon” and “parlor” guns. These were made as both rifles and pistols, mostly as single-shots. From introduction to discontinuance soon after World War I, parlor guns also fired other diminutive cartridges of 4.5 mm and 5 mm, as well as .22 CB Caps and .22 Shorts. Larger calibers, such as .32 Short and 9 mm are reported, but I speculate whether these are confused with “garden guns.” Many parlor guns were smoothbores, as are the European garden guns that typically shoot rimfire 9 mm shotshells for dealing with garden pests.

Art Nouveau and Straight Slots

Single-shot parlor rifles went through four basic metamorphoses. On Flobert’s original, the broad hammer acted as the breech block and had both firing pin and extractor machined on the hammer face. The second type had a separate extractor operated via a thumb piece. A third version finally sported a locking breech (akin to Remington’s rolling breech block) and a separate firing pin. The one presented here is the fourth incarnation, known as the Warnant type, identified by its vertically swinging breech block. The previous types continued in production even after development of the Warnant system, so the breech type doesn’t necessarily date any specific firearm.

An exceptionally petite rifle, this Flobert example bears a single identifying stamp, a Liege (Belgium) proof mark on the left side of the breech that dates its manufacture between 1853 and 1893. Weighing slightly more than four pounds and stretching only 38½ inches end-to-end, it is arguably less prone to knocking over lamps swinging about in one’s parlor than a full-size rifle. Measuring 23⅜ inches from muzzle to breech face, the octagon barrel’s rifling is only lightly engraved.

On the right- and left-hand sides of the stock at the action, the wood is raised in the style of muzzleloading rifles that would wear side plate and lock plate at these locations, giving the slim stock some beef where the most handling stress occurs. The abbreviated fore-arm stretches only eight inches forward of the art nouveau trigger guard. One can circle the dainty wrist with a thumb and forefinger with plenty of finger to spare. A steel plate caps the butt.

The Warnant-style breechblock pivots upward and pushes a simple sliding extractor backward upon opening. A single screw passing upward from the bottom of the breechblock retains the floating firing pin. The face of the firing pin is rounded rather than square, perhaps precluding sharp edges of a squared pin possibly puncturing a case rim, as the hammer mainspring is necessarily quite strong.

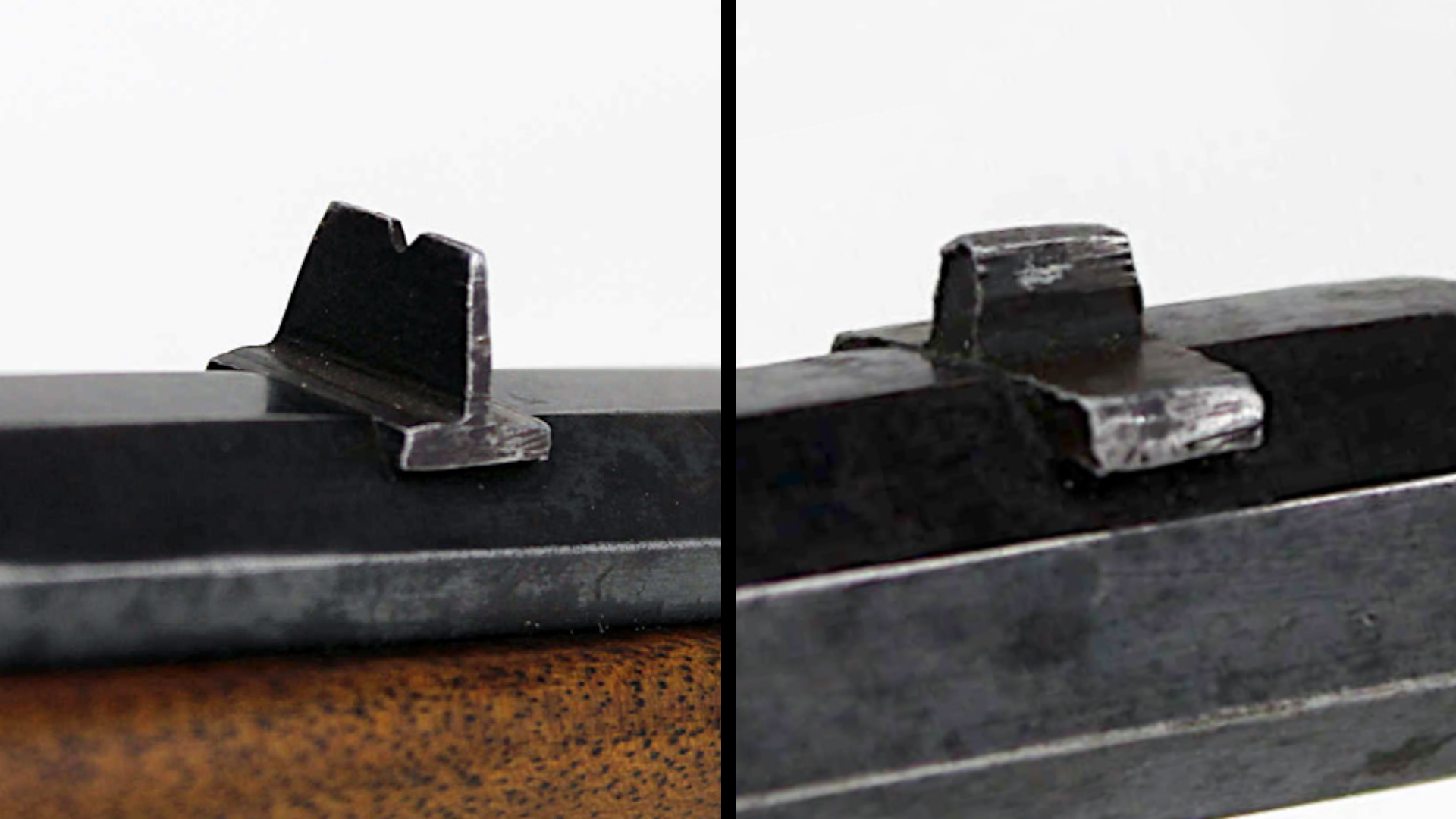

Three features serve to hold the breechblock closed. The first is that strong mainspring. Secondly, the flat hammer face is fully as wide as the breechblock, providing plenty of surface area to hold against it. Third, the bottom of the hammer face is recessed to fit over a ledge extending back from the breechblock. Upon firing, the wide hammer falling into place to strike the firing pin also acts simultaneously to hold the action closed, assisted by the strong hammer mainspring. Given the low pressures of 6 mm Flobert/.22 BB caps, it works adequately. The hammer thumbpiece is offset to the right so that it does not interfere with seeing the sights. The rear sight is a fixed notch, the front a simple fixed square, both dovetailed into the barrel.

This Flobert rifle came to me with the breechblock screw pivots and thumb latch missing; the owner was shooting it with only a single ungainly Phillips head screw keeping the breechblock loosely acquainted with the barrel. I fitted two new filister head gun screws for breechblock pivots; lacking a suitable thumb piece for the breechblock, I simply fitted another screw to match the other two.

Shoot, Don’t Shoot

Unsurprisingly, the owner had said that he experienced ruptured cases and gas and particles blown back into his face when shooting .22 Long Rifle cartridges in the rifle. A loose locking block aside, these weak actions intended for 6 mm Flobert/.22 BB Cap are not suitable for the more powerful cartridge—even though the .22 Long Rifle may chamber in them—it is absolutely an unsafe practice. Note that SAAMI maximum average pressure for the .22 Long Rifle is 24,000 p.s.i., and for the .22 Short is 21,000 p.s.i. Both these cartridges use smokeless powder, whereas the .22 BB Cap and 6 mm Flobert utilize only the priming to drive bullets.

I found no SAAMI or CIP pressure parameters listed for these latter powder-less cartridges, but certainly the pressures are a mere fraction of the smokeless powder cartridges. That would essentially make the .22 Long Rifle the equivalent of a multiple proof load in parlor guns intended for the 6 mm Flobert/.22 BB Cap. If the latter two cartridges are unavailable, the modern powder-less, primer-driven Aguila .22 Colibri with a 20-grain bullet generates similarly low pressure and may be safe in an individual rifle if it will chamber. The .22 Colibri is loaded onto a .22 Long case with a sedate bullet velocity of about 350 f.p.s.

The .22 Long Rifle cartridge physically fits this parlor gun because it lacks a chamber as such, being simply a straight bore running from breech face to muzzle. A dedicated chamber isn’t physically necessary as the rimfire 6 mm Flobert and .22 BB Cap cartridges headspace on the rims and bullets are the same diameter as the cases. Unfortunately, this leads the unknowledgeable today to assume that, because a rimfire .22 Long Rifle cartridge may similarly chamber, the parlor gun must be chambered for .22 Long Rifle. It’s a potentially hazardous assumption.

Think twice before shooting a parlor gun. While a few are of good quality and may still be fired safely with the proper ammunition, it appears the majority were manufactured as cheaply as possible from “malleable iron” or other soft metals; given the materials and their wear, many are certainly unsafe to shoot at all. Exacerbating the safety issue, a great many parlor guns are not stamped with the cartridge intended to be fired in them. The safest course of action is to hang parlor guns on the wall; if you think yours may be eligible as a shooter, have it checked by a knowledgeable gunsmith and use only the appropriate ammunition in it.

However, before shooting one in your living room, you may first want to check with your landlady.