“Germany was too busy trying to cut itself a piece of Poland to fire for a trophy (RWS) it had presented to bring about closer relations between that country, England and America.”

—The American Rifleman, October 1939

The euphoria that thousands of competitors experienced upon crossing the Camp Perry threshold for the 1939 edition of the National Matches was offset by the sobering news midway through this year’s program that Adolf Hitler’s German forces invaded Poland. Belying the seriousness of it all was a simple “Not Reported” entry in the score area of the results bulletin for Germany in the international smallbore RWS Match.

Ironically, the record entries and scores in 1939 served somewhat as a prophetic fulfillment from an earlier generation’s establishment of the National Matches for military preparedness. Reports of the conflict overseas prompted The American Rifleman to report that, “It was nice to know that, come what might, America boasted the best marksmen in the world and that there you were, surrounded by some 4,000 of them. The feeling of security was clinched when the U.S. Marine team of eight in the Herrick Match rammed 160 straight shots into the five-ring at 1,000 yards, one of the greatest shooting feats in history.”

Although U.S. involvement in World War II was not immediate, National Guardsmen and reservists who competed at the 1939 National Matches were among the many called to active duty based on President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s declaration of a limited national emergency.

The NRA’s installation of smallbore and pistol classifications this year was a popular response to the growing number of competitors in both sports nationwide and it was welcomed as a standardized system whereby regional winners could advance and attend the National Matches at the NRA’s expense.

“No effort will be made to incorporate .30 caliber rifle shooting in the program at this time,” reported The American Rifleman, “because of the fact that the selection of National Match Rifle Teams in state competitions and the payment of the expenses of such teams to the National Matches out of War Department funds has already solved many of the problems which the new program attempts to solve in the case of small bore rifle and pistol shooters.” And so, for the first time in National Match history, top performers in smallbore and pistol received NRA subsidies and results bulletins included breakouts for Master, Expert, Sharpshooter, Marksman and Tyro.

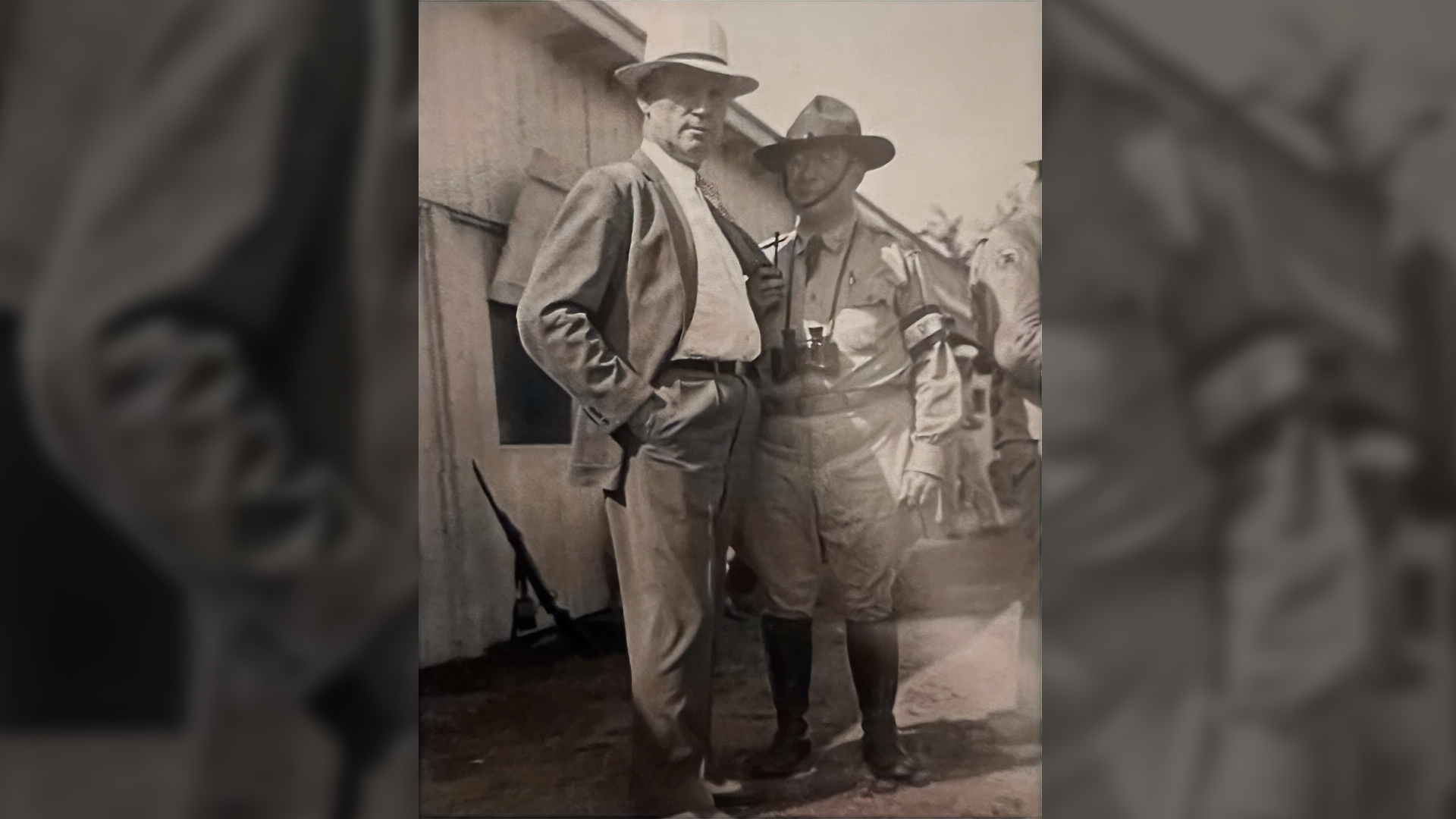

Col. Oliver Wood was appointed Executive Officer this year and oversaw a number of milestones and notable occurrences as his popular predecessor, Col. F.C. Endicott, was named the new Director of Civilian Marksmanship and Executive Officer of the National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice. In addition to the aforementioned classification system that was employed this year, the expanded pistol program featured the first NRA Grand Aggregate, based on eight center-fire and .22 caliber matches—the same number of events that now also comprised the Critchfield national smallbore aggregate.

In big bore, the M1 Garand made its debut at Camp Perry, although on a restricted, instructional basis only. The rifles were not used in competition.

Handgun highlights included wins by Emmett Jones of the Los Angeles Police Team for the inaugural Grand Aggregate title and in the NRA’s All-Around Pistol Match, introduced in 1935 as the first NRA three-gun championship aggregate for national honors. Jones outscored Detroit police competitors Harry Reeves and Alfred Hemming who finished second and third, respectively, both times. Percy Chapman of the U.S. Treasury Team claimed the National Individual Pistol title in the 100-man field, while the Marine Corps claimed the team event over 29 other squads. In its third year of competition, the International Pistol Match was won convincingly by the 10-man U.S. team over Canada, Great Britain and Cuba. Captained by Marvin Driver, the Americans were led by the high-scoring trio of Jones, Charles Askins and Walter Walsh.

The performance by Marines was strong as the perfect Herrick score and other individual scores would attest, but it was not a typical year for the Leathernecks. More often than not, the Herrick Match was a good indicator of who would win the national trophy, but this year the pattern did not hold true, as the Infantry defended both its team and individual rifle titles and laid claim to a record Leech Cup score by way of Cpl. Barger and his 105-19V. In fact, the Marine team finished third behind the Cavalry in the National Rifle Match. Individually, however, Marine Pvt. Alfred Wolters not only won the Wimbledon with a perfect score, but did so by firing a record-shattering 27 Vs, eight more than the previous mark. And in the President’s Match that featured a record 2,032 entries, Sgt. Thomas Jones earned the win, despite his own protest that his seventh shot at 1,000 yards was a four, not the five that he received. His protest was not allowed and surprisingly, marked the second time for such an occurrence in the 1939 high power program. In the Navy Cup Match, North Dakota civilian John Aiken challenged his own score to get a 95 instead of the 96 he received. But similar to Jones, Aitken received the trophy when his protest did not stand up.

And on the subject of protests, the shooter who challenged his own score the year before in smallbore and removed himself from contention for national honors earned victory outright in 1939. Ironically, Vere Hamer found himself pitted against Bill Woodring again this year for national smallbore laurels and unseated the three-time champion in a Critchfield Aggregate that this year carried a 3200 possible score with a greater emphasis on 50- and 100-yard shooting as the Dewar course continued to gain popularity.

Present day attention to the Dewar Match is not nearly what it was during the years between the wars, when it was not uncommon for shooters to bypass matches required for the Critchfield Aggregate. The Dewar held such a grip that entries in the Dewar Preliminary sometimes doubled those for national title contests. So important was the Dewar to the smallbore community that gaining membership was the high point of the program. And while competition today is still strong for positions on the team, it is more a function of one’s place in the tournament after the first two days and less of a concentrated effort.