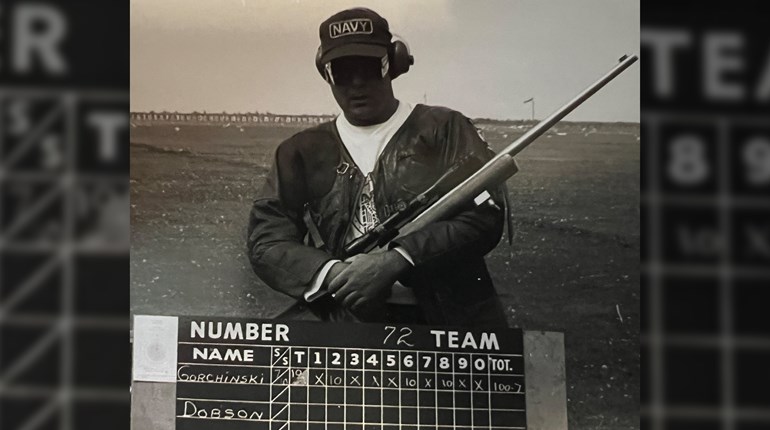

Not so long ago, determining bullet velocity was still guesswork for the home hobbyist. Then in 1948, a U.S. Navy Commander introduced handloaders to a remarkable free tool for accurately estimating muzzle velocity. All that’s needed is a ruler.

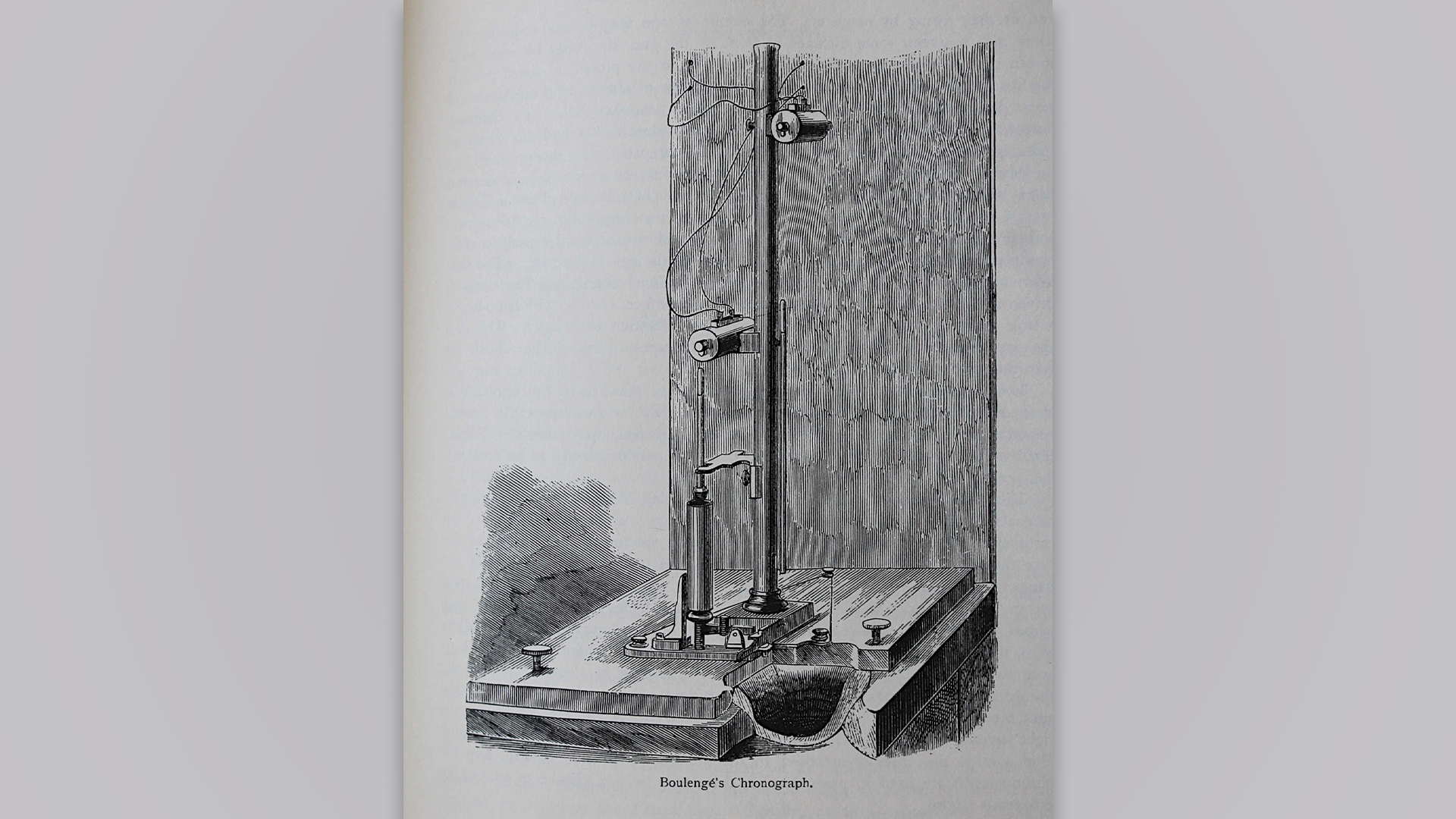

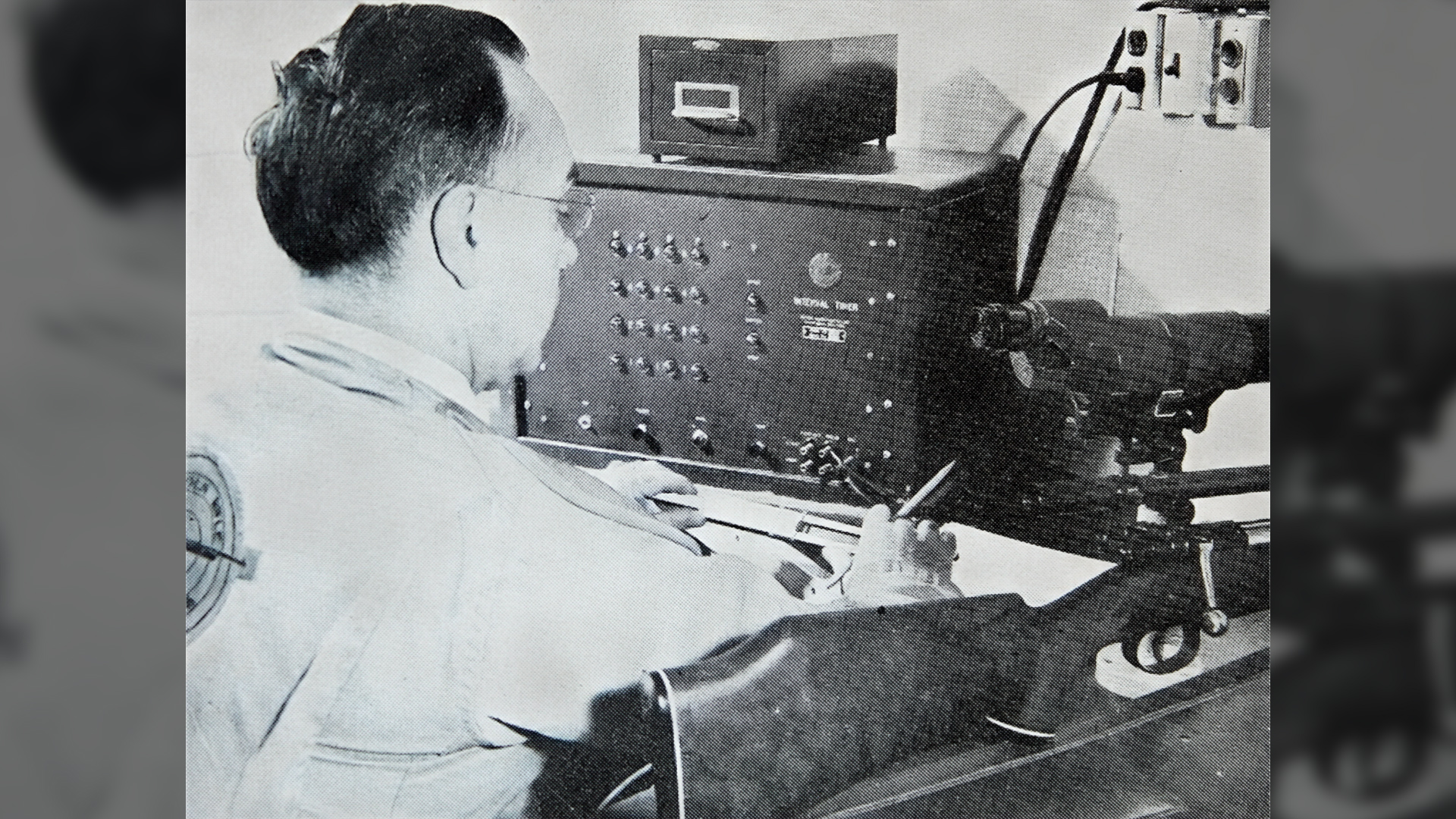

In the days before electronic chronographs, handloaders had no method for directly measuring bullet velocities. For the 200 years preceding the introduction of the somewhat cumbersome, vacuum tube-based Potter Electronic Chronograph in the 1950s, scientists, engineers and educated dabblers concocted all manner of mechanical devices, from pendulums recording the distance of rifle recoil, to shooting a bullet through a rolling paper in the quest to resolve bullet velocity. There were also attempts at utilizing theoretical mathematics, and perhaps surprisingly, it is one of the last that still works quite well.

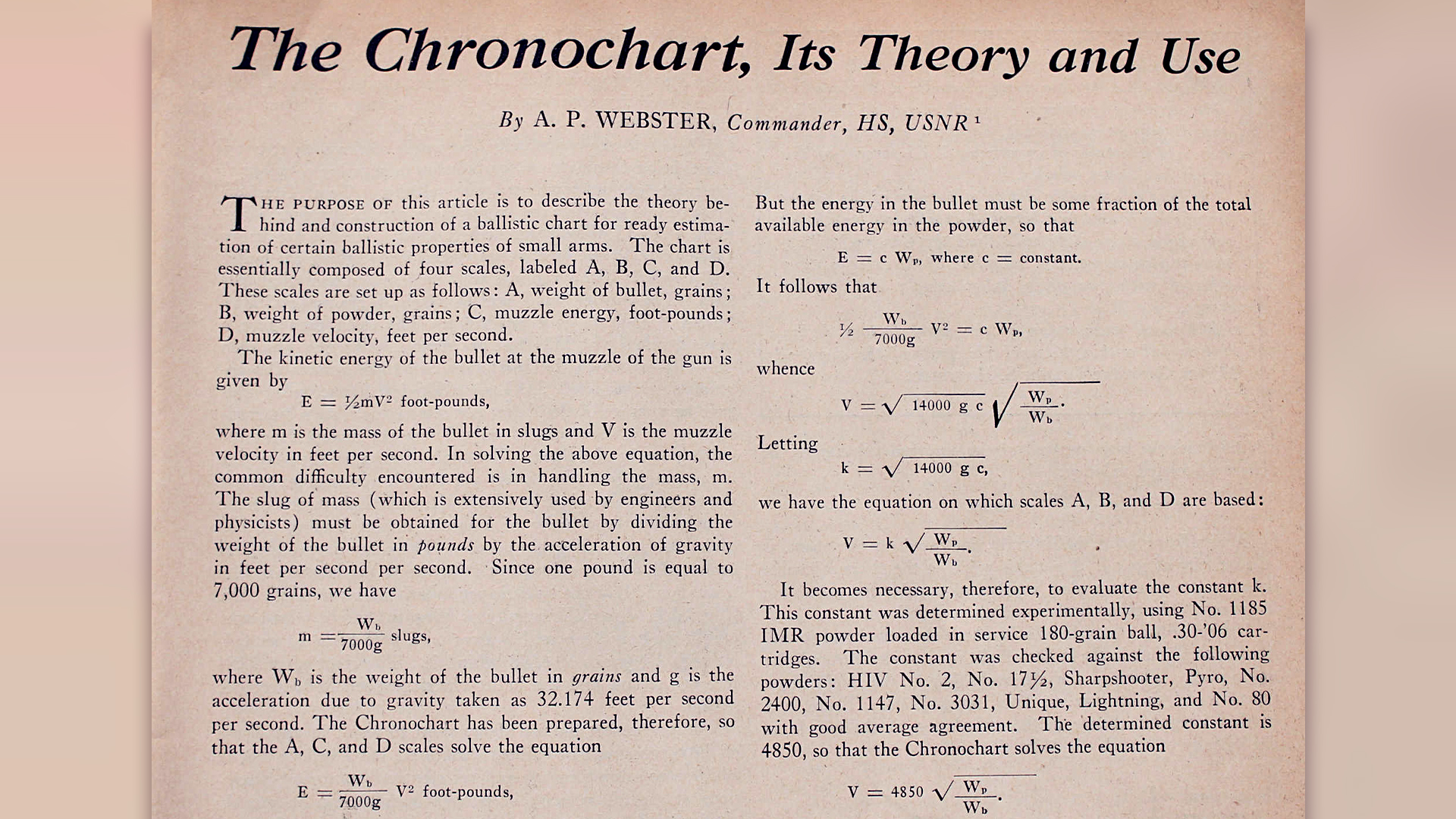

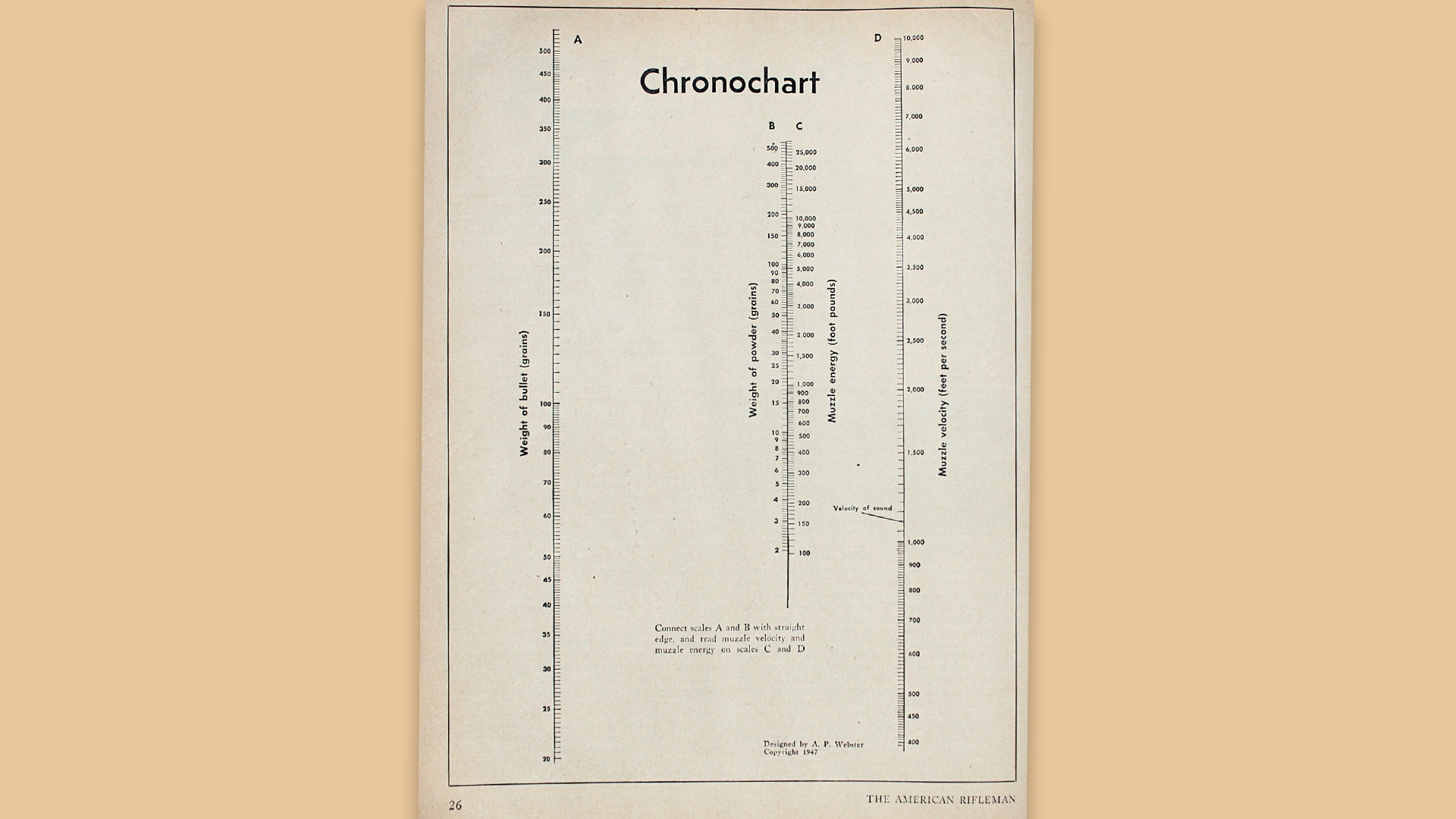

Webster’s Chronochart

In the May 1948 issue of NRA’s American Rifleman, Commander A.P. Webster (USNR) introduced his Chronochart, a simple vertical linear graph printed on the magazine page to estimate muzzle velocities and muzzle energies. The Chronochart has four vertical graphs listing bullet weight, powder charge, muzzle energy and muzzle velocity. The far left graph shows bullet weights from 20 to 600 grains. The second, center line is actually two graphs, reading powder charge weight on its left side, and muzzle energy on its right side. The fourth graph on the far right resolves muzzle velocity.

The quester simply inputs bullet weight and powder charge weight to resolve muzzle energy and muzzle velocity. To do so, he or she lays a ruler or other straight edge starting at the bullet weight on the left, and intersects the powder charge weight on the second graph with the straight edge. The straight edge continues to the right to indicate muzzle energy and muzzle velocity on the next two graphs.

Precision Estimates

To see how well it works, I checked it against some of my own handloads. One for 5.56 mm NATO Service Rifle competition is a 69-grain Sierra MatchKing bullet and 24½ grains of Reloader 15, which I chronographed at 2,740 f.p.s. I laid a straight edge to intersect those bullet and powder values on the Chronochart, which came up with an almost perfect 2,800 f.p.s. For my .30-’06 Sprg. M1903A4 Vintage Military Sniper Rifle, a 175-grain MatchKing over 46 grains of IMR 4895 chronographed at 2,550 f.p.s., the Chronochart hit it exactly on the nose at 2,550 f.p.s. It was a bit off—but on the conservative side—with a .204 Ruger handload (32-grain Nosler BT Varmint over 26 grains of Vihtavuori N135), which I chronographed at 4,019 f.p.s. and the Chronochart predicted to be 4,400 f.p.s.

How about a faster powder and a slower bullet? A .455 Webley, 260-grain bullet and four grains of W-231 clocked at 529 f.p.s., which the Chronochart indicated would be 71 f.p.s. faster at 600 f.p.s.

Key Constant

One of the keys to the Chronochart’s accuracy (or accurate estimation) is in Webster’s use of a mathematical constant based on one grain of any particular powder producing about 165 foot-pounds of energy. Webster determined that constant by experiments with IMR 1185 (used in some service ammunition) and checked against other powders of the day available to handloaders (among which only IMR 3031 and Unique are still around). Because not all powders—especially today’s many newer powders, 80 years later—produce exactly 165 foot-pounds of energy per grain, the Chronochart cannot be absolutely precise across the board.

Precise? Well, define “precise” when it comes to predicting bullet velocities in 1948. The Chronochart is certainly far more precise than “ballpark,” and precise enough for the home hobbyist lacking an 18th century pendulum setup or today’s selection of affordable electronic chronographs. And Webster didn’t claim precision, only that his Chronochart delivered useful estimates.

“I do not expect the use of my chart to result in any disuse of the [laboratory] chronograph or ballistic pendulum,” Webster humbly concluded his article. “I feel that the chart can be a useful tool to all shooters, and if carefully used, it has a definite application where the experimenter desires to estimate the velocities of various loadings.”

Though more of a curiosity today, given our access to direct measurement, Webster’s Chronochart, indeed, still delivers useful estimates.