WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

I like the .380 Auto cartridge and the mid-size pistols that shoot it—especially the Beretta Model 84. Not only does it look cool, it has a 13+1-round capacity, fits my hand well and points naturally.

That said, the Model 84 has snappy recoil, since it is a blowback-operated pistol, which have a reputation for having more felt recoil than similarly designed locked-breech guns. For example, while the Model 84 feels snappy, the Smith & Wesson M&P .380 Shield EZ, a locked-breech pistol of the same chambering, has a comparably pleasant and softer feeling recoil impulse.

My Beretta Model 81, chambered in .32 Auto, is just the Model 84 in a different cartridge. Also blowback-operated, the .32 Auto round has about half the recoil of the .380 Auto. As a result, the Model 81 is delightful to shoot. It’s easy to get .380 Auto recoil to feel like a .32 Auto if you handload.

Before I get to the load data, here’s the thing about blowback guns. It does not take much recoil force to make them cycle. You can load light .380 Auto rounds and the gun will still function. The gun can cycle, even if the load is so light that the bullet does not leave the barrel. I’ve experienced this personally and it is dangerous. The gun “fired,” that is, the slide cycled and loaded a fresh round from the magazine, but the bullet did not exit the barrel. Fortunately, I became aware of the stuck bullet before I tried to fire it again. It’s easy to see how a person could be fooled into thinking everything is normal because it cycled, but if you fire the gun with a bullet stuck in the barrel, it might explode. The gun could be damaged and you could be seriously injured. Be extremely careful in your load development.

Most .380 Auto ammunition has 90- to 102-grain bullets leaving the Model 84’s 3.8-inch barrel at between 900 to 1,000 f.p.s. A common bullet weight is 95 grains, and traveling at 950 f.p.s. from the 23.3-ounce Model 84 produces 1.77 foot-pounds of recoil (powder charge weight was excluded for these recoil calculations).

Ballistics of a .32 Auto run a 60- to 73-grain bullet between 900 to 1,000 f.p.s. A common bullet weight for .32 Auto is 71 grains, and traveling at 950 f.p.s. produces 0.99 foot-pounds of recoil in the same weight gun.

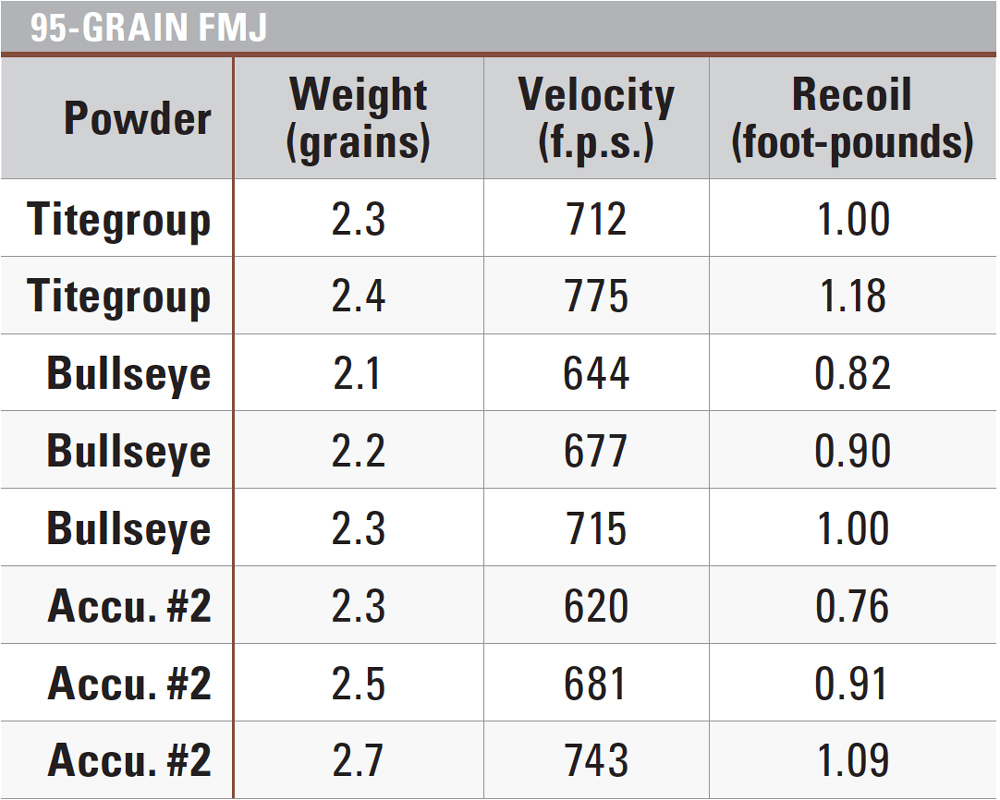

How much do you have to slow down a .380 Auto bullet to produce the same recoil as the .32 Auto? A 95-grain bullet at 710 f.p.s. will match the 0.99 foot-pounds of recoil. A 100-grain bullet—another common weight for handloading .380 ammunition—had to be slowed down to 675 f.p.s. to produce 0.99 foot-pounds of recoil.

Digging through loading manuals, I found all sorts of loads to try. In many cases, the starting loads produced the desired low velocities. My tests had important criteria in mind. First, I did not use loads below 600 f.p.s., as there’s no need to go below it for pleasant shooting .380 ammo. Also, below 600 f.p.s., some loads can produce erratic velocities, risking a stuck bullet.

Next, I watched for velocity extreme spreads. Some powders don’t work well with light loads. Wide extreme spreads might indicate inconsistent ignition which could result with a stuck bullet. For example, I tried several loads with Vihtavuori N320, but it had wide extreme spreads, so I didn’t consider it suitable for low-speed .380 rounds. (But it works well in full-powered .380 ammo.) I focused on fast-burning powders, since they are likely to reach higher pressure with light loads, which might help them burn more reliably to keep speeds more consistent.

Several powders produced light-shooting rounds with 95- and 100-grain bullets, including some in the low-600 f.p.s. range. Recoil from several light loads was below half the recoil (1.77/2 = 0.88 foot-pounds) of factory ammunition.

The Beretta Model 84 cycled reliably with everything I tried, even at sub-600 f.p.s. speeds. By comparison, my Smith & Wesson Shield EZ won’t cycle reliably with bullets in this weight range below 800 f.p.s.

An unexpected aspect—it’s easy to rack the slide on the Shield EZ pistol (a major selling point), while it can be difficult to rack the Model 84 slide. With this in mind, one might predict that light loads would be more likely to cycle the Shield EZ than the Model 84. But it’s actually the opposite, which speaks volumes about the difference between blowback and locked-breech guns.

Be aware that small changes in powder charge weight can produce large differences in velocity. The small case capacity of the .380 round is why. A 0.1-grain change of powder can result in a 50-f.p.s. speed difference. That’s why you need to develop your own loads. Using powders from different lot numbers might produce different speeds than I found, so start in the mid-range of published load data and work your way down. You don’t want a stuck bullet if your powder happens to produce lower speeds reported here. Add differences in components and chambers or barrels, and you can see why results can differ. Be cautious in your load development.

Testing was performed with Beretta Model 84 and Zenith Girsan MC14 blowback pistols. I don’t know how other blowback guns, such as a Bersa Thunder, Walther PP series, Hi-Point, etc., will function with these loads. Again, work down from mid-range loads to see what works best.

I was delighted to learn these low recoil loads cycled in my Taurus PT 738 .380 pistol. A micro-compact, locked-breech pistol, even the weakest loads in the table (2.3 grains of Accurate #2, 95-grain FMJ) cycled the Taurus reliably. The light recoiling load encouraged me to practice with the 10.2-ounce Taurus, which can be brutal with full-powered ammunition.

Light .380 Auto handloads can reduce recoil by half that of factory ammo, and still operate blowback pistols, such as the Beretta Model 84 and some micro-compact .380s. Try some to put the fun back into your range trip.