WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

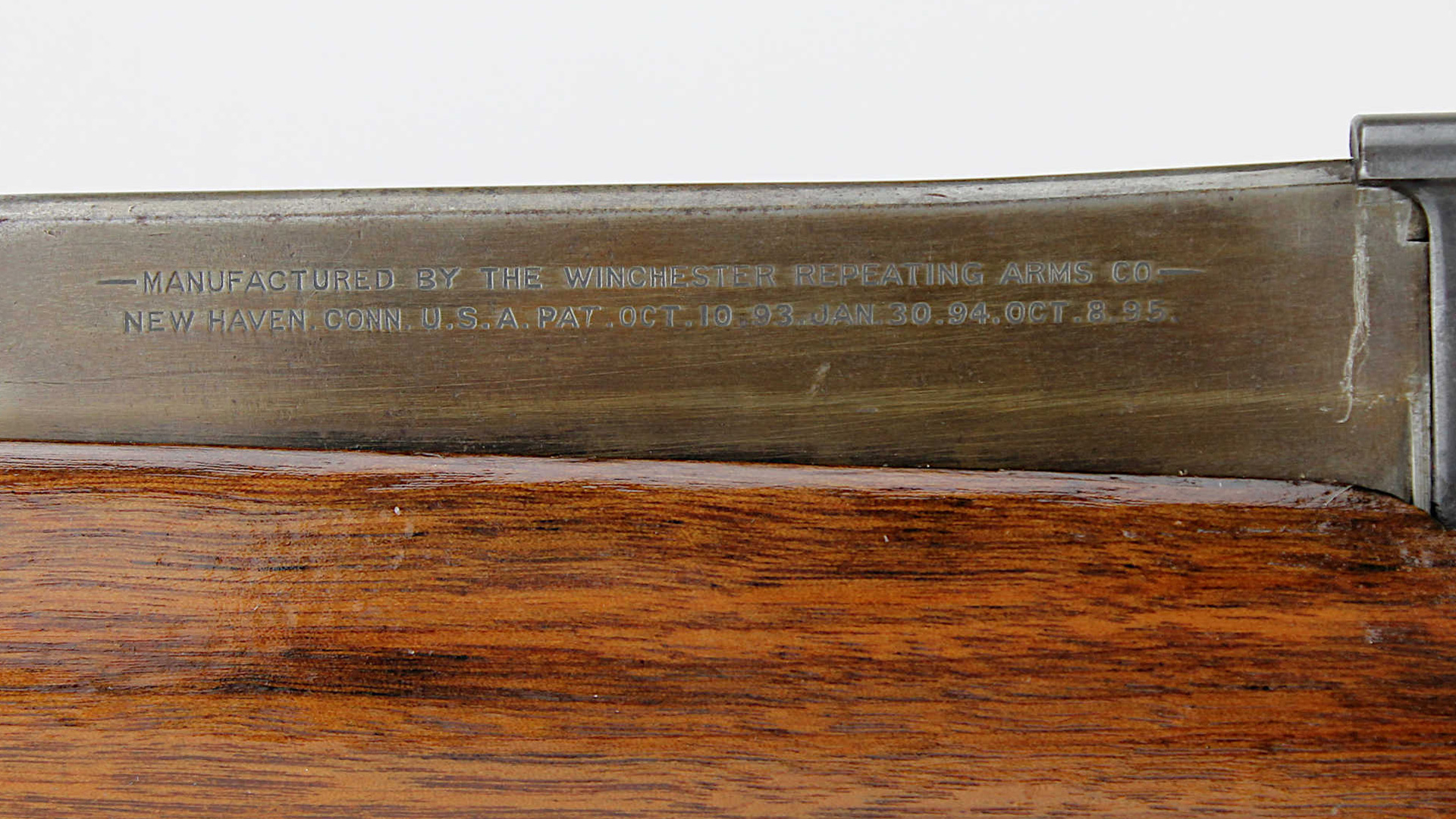

James Paris Lee, the same Lee associated with the famous Lee-Enfield rifle, designed the Lee Straight-Pull Rifle of 1895 to satisfy United States Navy requirements for a new small arm. Winchester manufactured only a small percentage of Model 1895 rifles for the civilian market, and even fewer Sporting Rifles for hunters.

After securing patent rights from James Paris Lee, Winchester manufactured 20,000 Model 1895 rifles. The U.S. Navy purchased 15,000 in two contracts, the first for 10,000 rifles (1896) and the second for 5,000 (1898). The Navy and Marine Corps employed the Model 1895 rifles in the Spanish-American War, the Philippine “insurrections” and the Chinese Boxer Rebellion at the turn of the 20th century, but was already transitioning to the U.S. Army’s .30-40 Krag-Jorgensen rifle by 1899 after higher-ups decided all services should have the same small arms and ammunition. Still, several U.S. Navy ships had Model 1895 rifles aboard as late as the 1920s, and the Washington Navy Yard still listed some in inventory into the 1950s.

Winchester also made about 4,300 military rifles for commercial sales. While all are uncommon enough today, the shorter civilian Sporting Rifle version presented here is quite a rarity, perhaps only 1,563 making it to dealer shelves before Winchester ceased production in 1902.

Smallest military caliber

A new, high velocity cartridge came with the Navy’s new rifle. The 1896 Navy manual, “The United States Navy Rifle, Calibre 6 Millimeters, Model 1895” describes the “standard Navy ball cartridge” as a 135-grain hardened lead bullet with a cupro-nickeled steel jacket, driven at 2,460 f.p.s. by a 33.2-grain charge of “Troisdorf smokeless powder.” The manual describes bullet performance in the parlance of the times: “With this velocity a penetration of 62 inches in pine at five feet from the muzzle is obtained. The penetration in steel boiler plate is about 7/16 inch at the muzzle and 3/8 inch at 100 feet.” Apparently, however, bullet weight was reduced to 112 grains and velocity upped to 2,550 f.p.s. by the time the manual was published.

This 6 mm cartridge would be the smallest diameter bullet used in any nation’s general-issue military rifle until the advent of the 5.56 mm NATO round nearly 70 years later. Universally called the 6 mm Lee Navy, the rifles were stamped with the original cartridge designation, “.236 USN.” The “.236” certainly refers to the bore diameter, not the groove diameter, which is cut to accommodate .244-inch/6 mm bullets.

Cam-Action Rifle

Possessed of a unique operation, the Lee Straight-Pull action is generally called a “bolt action” because it has a manually operated bolt with a handle, but the bolt does not rotate in the classic manner, nor is it technically a straight-pull like the Swiss Schmidt-Rubin bolt actions such as the K31 that automatically rotate their bolts when pulled straight backward. Nor does the Lee Straight-Pull have locking lugs in the expected sense. Instead, the square bolt works on a camming action; pulling backward on the bolt handle (actually called a “cam lever”) causes it to cam upward before it can move backward.

For bolt locking, a fly engages the bolt to keep it locked until the trigger is released. A shoulder on the bolt bears against a recoil shoulder on the receiver to take the thrust of the fired cartridge; the geometry of these shoulders is such that bolt thrust is angled slightly downward, which aids in keeping the bolt locked on firing.

Controls on the left side of the receiver are the bolt stop, bolt release and a firing pin block. The bolt stop is disabled by pulling it outward away from the receiver and pushing it down to allow withdrawing the bolt from the action. Pushing the bolt release down unlocks the cocked bolt; this is the only way to open the action when it is cocked, other than pulling and releasing the trigger. The firing pin block serves as a safety, locking the firing pin when the action is cocked and the firing pin block is raised to the up position. The trigger and sear can still move when the firing pin block is engaged.

Though the Lee Straight-Pull is intended to be loaded with a five-round clip that drops out the open bottom of the receiver after loading the magazine, the magazine can be loaded with individual rounds without the clip. Typical of the era, the Sporting Rifle’s front sight is a silver blade pinned to a short ramp, the rear sight a semi-buckhorn dovetailed into the barrel and adjusted with a sliding, serrated elevator. The Winchester-logoed pistol grip cap is either gutta percha or hard rubber; the butt plate is steel. The stock sports a slight Schnabel and finger grooves; forearm and pistol grip are quite slim. All that milled steel gives the Sporting Rifle a heft of just more than seven pounds.

Ironic Ammo

This Sporting Rifle came into my possession with a serious problem: the cocked bolt would not open without first pulling the trigger, making it impossible to withdraw an unfired cartridge from the chamber. I learned the June 1982 issue of NRA’s American Rifleman magazine has an “exploded view” of and disassembly instructions for the Lee Straight-Pull Rifle, of which a friend sent me a copy. Upon disassembly, I discovered a broken bolt release to be the cause of the malfunction. An online search eventually turned up an original for replacement.

Ammunition for the Lee Straight-Pull Rifle is strictly a custom-die handloading proposition. In a twist of irony, the present .220 Swift cartridge is based on the obsolete 6 mm Lee Navy/.236 USN case and can be used to remake its parent, though necks will be short and case rims may need to be turned down to suit a specific rifle. Load data is hard to come by, but according to P. O. Ackley’s 1962 “Handbook for Shooters and Reloaders,” 32.5 grains of IMR 4064 under a 112-grain bullet will closely duplicate the original Navy load at 2540 f.p.s.

A period Winchester catalog lists both the Lee Straight-Pull Sporting Rifle and military “musket” at $32.00, which equates to about $1,160 today. Though rarer than the military rifles, Sporting Rifles in NRA Very Good condition are selling in the $2,000 neighborhood while military rifles with United States Navy markings fetch about $400-$600 more.