WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

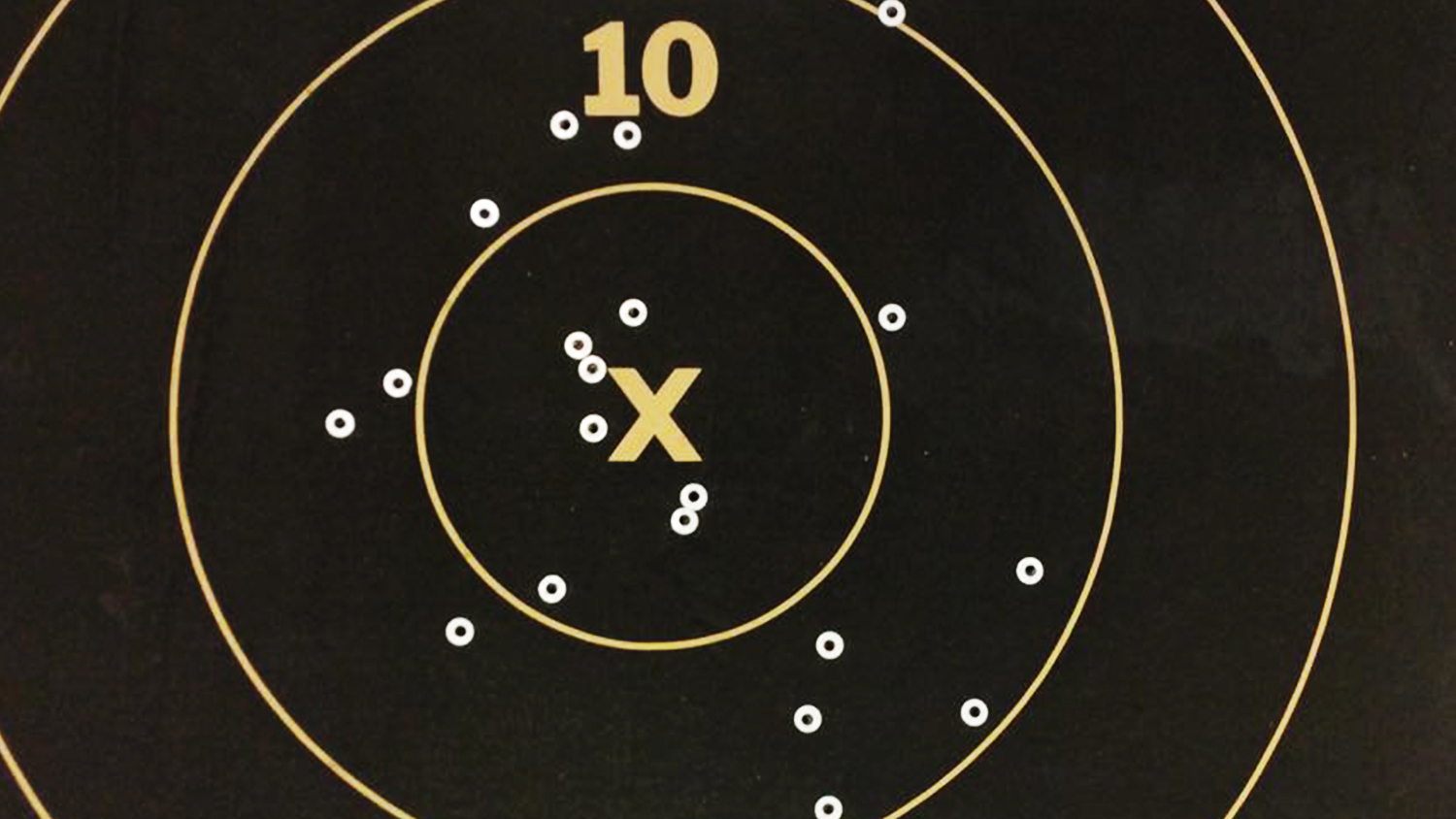

Above: A record “clean” (perfect score) fired at the Inter-Service matches using a U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit Custom Firearms Shop-'smithed National Match M16A2 at 1000 yards with our handloads.

In this article, rather than discussing specific handloading techniques, we'd like to discuss integration of your handloading regimen into your overall plan of training (and winning!). There are many specialized techniques intended to enhance accuracy, and it can be tempting to dive in full force in order to have the maximum chance of shooting a top score.

However, a careful analysis of your goals may guide your handloading practices—and these may change as your goals and skills change. For example, one of our staff was once asked at a match by an earnest young man if he should turn case necks for his un-accurized DCM M1 Garand. The rifle was capable of holding about four MOA, and couldn't exploit this advanced technique. Moreover, the shooter was new to competition and still in the Marksman class.

Obviously, this gentleman's needs would have been better served, time-wise, by copious dry-firing and practice with adequately-accurate ammo, expeditiously produced (plus a rifle re-build). Is the primary goal to add points to one's score? If so, then depending on one's skill level and rifle capabilities, more points may likely be earned through quality practice and making lots of *good* ammo, rather than by spending lots of time trying to make world-class ammo (and not practicing).

A realistic assessment of the efficient use of your limited time resources may mean that practicing more often, or dry-firing in the evenings, may be far more beneficial that spending those hours at the loading bench, super-tuning your ammo. When your ammo can no longer keep up with your skills, however, then it may be time to consider refinements. Very accurate ammo for High Power purposes can be produced efficiently on good equipment with good technique.

What are your thoughts and experiences along these lines? Let us know at [email protected]

In closing, one of our staff once saw a relatively new shooter score a 450 out of 500 on the 100-yard reduced course. He was shooting an unmodified SKS with copper-washed, steel-core Chinese surplus ammo! His sole concession to accuracy was an inexpensive, after-market peep sight mounted to his receiver! Given the small size of the 600-yard reduced 10-ring (1.7", if I recall correctly), and the fact that 20 out of 50 shots were fired at that tiny 10-ring, this was *definitely* a shooter who could have made good use of a better rifle and ammo. He practically drew a round of applause when his score was totaled.

A reader asked how one knows when to anneal case necks to remove work-hardening. First, there are many recommended methods of annealing out there, and not all of them work, so some good research is needed before starting on this venture. Second, frequency of annealing varies with one's needs, and there is no hard-and-fast rule.

Several National Championship-level Black Powder Cartridge Rifle competitors anneal their straight-wall Sharps cases after every firing! A person whose dies over-work the case neck, sizing down several thousandths too small and then expanding up several thousandths, will likely need to anneal sooner than the bolt-gunner with a tight neck chamber that allows brass to expand only .001"-.002" upon firing. For normal High Power competition purposes, a happy medium might be to anneal every third or even fifth firing. Annealing makes neck tension (and therefore, bullet seating) very uniform. If you start to see variances in neck tension, it may well be time to anneal that lot of brass.

SSUSA thanks the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit for allowing the reprint of this article.