From the vault: Rising from humble roots south of the border, the evolution of high power silhouette competition rifles had almost come full circle by the early 21st century. As published in the June 2002 issue of Shooting Sports USA.

High Power Silhouette Rifles

Story by Scott Engen

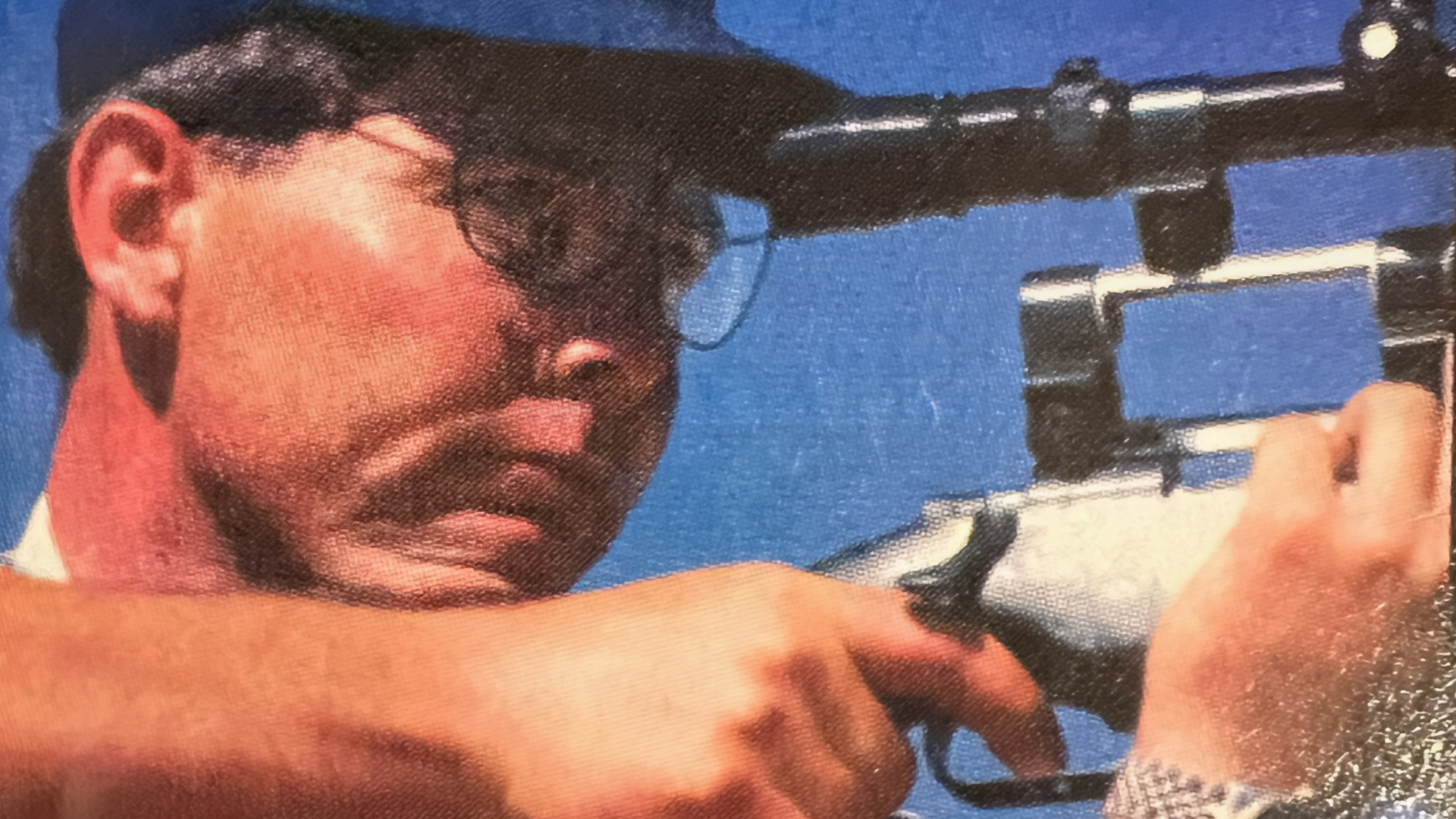

Photos by NRA Staff

Like fresh salsa and jalapeños, metallic silhouette high power rifle shooting is one of the hottest imports from old Mexico in the last half-century. Born of humble, rural roots with a “run-what-you-brung” attitude, succeeding decades have seen centerfire long-gun shooters push the technical envelope with regard to guns, cartridges, optics, mounts and ergonomics.

This is a story of hardware evolution and adaptation, of shooters and gunsmiths pushing the envelope on the rules, and seeing the rulebook react by closing off some avenues of equipment development. It’s about where high power silhouette rifles came from, where they are now and where many experts in the field see them headed.

CROSSING THE BORDER

When the high power metallic silhouette game began to trickle northward in the 1960s, both rules and rifles were still pretty flexible. Most shooters dusted off their trusty deer or elk rifle, made sure the rings were tight and the scope was zeroed and they had enough ammunition to finish the match. The traditional .30-caliber bolt gun was the rule rather than the exception on the firing line.

Jack Hill of Placenta, California, was there from the beginning.

“I shot my first U.S. Nationals in 1974, back when we only had three animals, with no pigs,” Hill reminisced. “I used my deer rifle—a sporterized 1903-A3 Springfield in .30-06, topped with a 4X Lyman Alaskan scope.”

After the 1974 match, the pace of changes in equipment began to accelerate. Hill recounted that Roy Dunlap and Earl Hines, both well-known competition gunsmiths of the day, proposed that the equipment for the silhouette game move from traditional sporter rifles toward match rifles with thumbhole stocks and heavier barrels.

The open-class rifle rules called for a rig weighing less than 10 pounds, two ounces. The Remington 700 Varmint Special, usually chambered in .308 Winchester, quickly became the standard by which most other silhouette guns were measured. Affordable and accurate right out of the box with a trigger that could be easily tuned by a competent gunsmith to the user’s taste, the Remington 700 series still holds the lion’s share of the ram-slamming market after almost three decades of competition.

Much of the initial success of the Remington 700 Varmint Special in the silhouette game must be attributed to the factory .308 Win. chambering. By the mid 1970s, many years of development and millions of dollars had already been spent by both government and private industry to wring the maximum accuracy out of the mid-length .30-caliber case for both combat and competition applications. The .308 Win. round certainly had the retained energy to reliably topple the car-door-sized rams all the way out at 500 meters, and the recoil level was manageable for most shooters.

Excellent match bullets were readily available from companies like Sierra, Hornady and others, and match-grade factory and military cases were plentiful. Combined with military surplus powder like the original BL-C being sold mail order by the bushel basket at bargain basement prices, and the .308 Win. quickly became the ram-ringer’s cartridge of choice.

As in most sports, the rulebook tends to dictate the hardware. Two classes of high power silhouette equipment quickly became established, an open class for heavy guns and another for the lighter sporter-weight rigs. Each class developed a following, with substantial crossover from one class to another. More recently, additional classes for guns like the military service rifle have been announced, with varying degrees of shooter acceptance. In addition, entire classes of competition rifle activity for smallbore, cowboy lever-action, blackpowder cartridge and even handguns have spun off into their own events, with their own dedicated followings.

The rapidly growing sport attracted many new shooters in the late 1970s and early 1980s. One was Teresa Everheart, at the time a teenager who would go on to shoot in every U.S. National Championship from 1980 to the present, winning several national titles along the way.

“I started in 1980 with a Remington Varmint rifle in 7 mm-08 and a Weaver T-16 scope,” recalled Everheart. “Quickly I started begging to shoot the .308 because the 7 mm hunting bullets weren’t rolling over the rams as well as a heavy .30-caliber match bullet would. After a while, I moved on to a chin gun in .243 Winchester.”

The evolution of the “chin gun” stock is an interesting side story in the evolution of high power silhouette rifle design. While the exact origins of this stock design concept are somewhat murky, many have credited Don Brook, an Olympic rifle shooter from Australia, with one of the first introductions of a workable model of his own manufacture, which he used successfully in international rifle competition in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

The chin gun design uses a very high comb on the buttstock, which puts the shooter’s head in an upright position. The “weld,” or point of contact between head and rifle stock, then moves from under the shooter’s cheek to a point under their lower jaw. Naturally, the gun’s optical axis needed to be raised as well, so the scope became attached to the rifle by way of an extended base and mount, or by using a series of interlocking scope rings and metal tubes. While highly adjustable, some such mounts had a distinctly “Rube Goldberg” flavor, and the entire chin gun concept was abandoned a few years back by the NRA Rules Committee in favor of more traditional stock designs.

The move down the bore-size scale is another interesting trend. Adventurous silhouette shooters soon moved down a notch from the .308 Win. to one of the several 7 mm wildcats that were based on the .308 case, or to one of the stubby-cased 7BR variants. Reductions in felt recoil, along with major improvements in bullet design and propellant technology, promised the 7 mm crowd a competitive edge, be it real or imagined.

The next logical step down the ladder was to one of the 6 mm class cartridges like the .243 Win., 6 mm Remington or one of the squatty 6 mm wildcats. Houston, Texas, gunsmith William Zander, a national-class competitor with well more than a decade of experience in the game, recalls the effect of the switch to the 6 mms. “The scores went up dramatically, often from 26 or 27 animals to 35 or 36 almost overnight,” Zander said.

However attractive the instant improvement in raw score was, it was here that simple physics collided headlong with competitive innovation. First, the little 6 mm pills, even those on the heavy end of the scale, just didn’t retain enough energy to reliably dump a ram at 500 meters. Assuming a low or off-center hit, throw in a little forward slope to the target rail, add a little headwind to help hold the critter upright and then add a few extra pounds of sticky gumbo mud on a rainy day, and many competitors would watch in dismay as a ram could be rung soundly yet refuse to fall, thus scoring as a miss.

Terminal ballistics aside, another major problem was all that burning powder trying to get through a little 6 mm hole in the barrel. Throat erosion was found to be severe, and a barrel’s useful accuracy life was therefore quite limited. Many shooters were getting only 1,000 rounds out of a brand new, mega-buck 6 mm match barrel and some reported that the drop-off in accuracy was both pronounced and sudden, sometimes occurring right in the middle of a match.

Just like a shooter adjusts sights for windage, having made a bold correction in one direction, fires a shot and observes the result, and then takes a couple of clicks back to center, so too has the ideal bore-size debate stabilized, at least for the moment. Today, the most popular bore size in high power silhouette looks to be the 6.5 mms. Many shooters are settling on the .260 Remington, a popular 6.5 mm-08 wildcat legitimized through gunwriter Jim Carmichael’s cooperative efforts with the folks at Remington.

Others are favoring the venerable 6.5x55 Swedish, a military service cartridge that has long been a staple of European and Scandinavian shooters, with a near-legendary reputation for hard-hitting accuracy and wind-bucking ability. Good 6.5 mm match bullets are readily available and barrel life is reported by many to be twice that or more than the 6 mms, which is nothing but gravy for any shooter, regardless of budget.

Stock materials have also seen an evolution. A solid chunk of walnut has yielded the right of way to resin-impregnated laminated hardwood, fiberglass and even exotic synthetics like carbon fiber. Zander said that even here, working with the latest stock materials, some drawbacks have been observed.

“Some of the exotics like carbon fiber are tough to machine,” he said. “The carbon-fiber dust is conductive, and when it gets into machine-tool motors, it tends to arc and burn them up. Most shooters are moving to some sort of synthetic like a McMillian or H-S in order to keep the stock stable in the rain or in changes in humidity. Most of the silhouette guns today are pillar-bedded with some type of metal-filled epoxy like Devcon or Brownells, often with the stainless steel powder added.”

Since you can’t hit what you can’t see, silhouette scopes have undergone changes, too. Long gone is the humble 4X Lyman Alaskan of several decades ago.

“The Weaver T-series was a great leap forward,” Hill recalled. “It was very repeatable. Now Leupold and Burris are showing up in large numbers. For high power silhouette you need a scope with enough elevation to go from the chickens out to the rams in one revolution or less which is about nine to 12 minutes of adjustment. If you have to go beyond one turn of adjustment, you tend to get lost as to where you are. Most shooters are using around 20X magnification, especially out here in the West with the wind and mirage. If you’re back East with less wind you can go up to 30X or more.”

So, within about a quarter-century we’ve come full circle, from traditional sporters to standard varmint rifles and heavy-barreled thumbholes, to exotic “chin guns” and back to an off-hand-stocked varmint rifle. Where does high power silhouette hardware go from here?

Both Zander and Everheart see the best direction for the sport moving toward something that resembles an across-the-course NRA match rifle, barreled in some 6.5 mm or 7 mm mid-range cartridge.

“In order to get more shooters and activity in high power silhouette, we need to get some crossover offhand shooters from the NRA high power ranks,” Everheart said.

“I’d like to see the NRA rules allow for more interchangeability of guns between the two sports,” Zander added. By contrast, Hill feels the current trend toward .22 and 6 mm NRA match rifles will tend to exclude them from double duty in the high power silhouette game.

Learn more about high power silhouette at the NRA Competitive Shooting Division website.