Here in the digital vastness of the future, afficionados have a facet of buying and selling firearms formerly not available to those whose frame of reference is pre-internet—the online auction. The internet expands our scope of possibilities far beyond offerings in local gun shops or catalogs. However, it isn’t all unicorns and rainbows, as basic economics is still at work.

An FFL dealer acquaintance of mine is occasionally tasked with selling online a collection—or perhaps more accurately, an accrual—of firearms. Someone may wish to pare down a collection, or to make room in a gun safe or to dispose of a deceased husband’s confusing conglomeration of guns. Very often, these accruals include firearms of little to no value, which brings up the aspect of internet economics. Case in point here is a pair of throwback .22 Long Rifle rifles.

Two-fer .22s

Utilitarian rather than classic collectibles, both .22s are in NRA Very Good to Excellent condition possessing values roughly in the $100 neighborhood. But each suffers a minor problem, which necessarily reduces their value further, as economics demands a lesser selling price to offset the cost of repairs to the buyer. The savvy online buyer will also consider into the final cost the shipping fee and fee paid to his or her local FFL for the transfer. Deducting the estimated repair cost, the FFL’s commission, the online auction house’s seller’s premium and the already low value of these .22s means the former owner would pocket maybe 20 to 30 bucks per rifle. Honestly, even without need of repair, the rifles were hardly worth the time and effort to put online.

Sometimes, hard capitalist economics comes out in our favor, especially when the seller’s major goal is to simply divest himself of stuff in which he’s lost interest. That’s why yard sales are so popular. Faced with the expectation of earning essentially an hour or two of minimum wage to photo, describe, upload, package and ship the rifles, the FFL, who’d asked my help in identifying some of the old rifles, instead accepted my offer of a $100 bill to hand-carry away the brace of .22s. Let’s see if they’re worth it.

Store brands

To an avid rifleman, the first .22 is decidedly pedestrian, a bolt-action J.C. Higgins Model 103.229 “store brand” made for Sears, Roebuck & Company. Store brand guns are the Rodney Dangerfields among firearms, getting no respect. Stores like Sears, Montgomery Ward, Western Auto and others commonly sold their own brand-name firearms up into the 1970s, when the practice ended. Many shooters don’t stop to consider that retail stores didn’t manufacture their own firearms, they were made by—big surprise—firearms manufacturers. Manufacturers of J.C. Higgins-branded firearms for Sears included Marlin, High Standard and Savage, but because these names aren’t stamped on the guns, they garner undeserved disdain from most shooters, regardless of their pedigree. Ignorance may be the major reason, but lacking snappy names and saddled with boring and forgettable model numbers like “103.229” doesn’t help. (As a side note, John Higgins was a bookkeeper who worked at Sears from 1898 to 1930 and eventually served as the company’s vice president. Sears later replaced the J.C. Higgins sporting goods brand name with that of baseball legend Ted Williams.)

It’s a Marlin

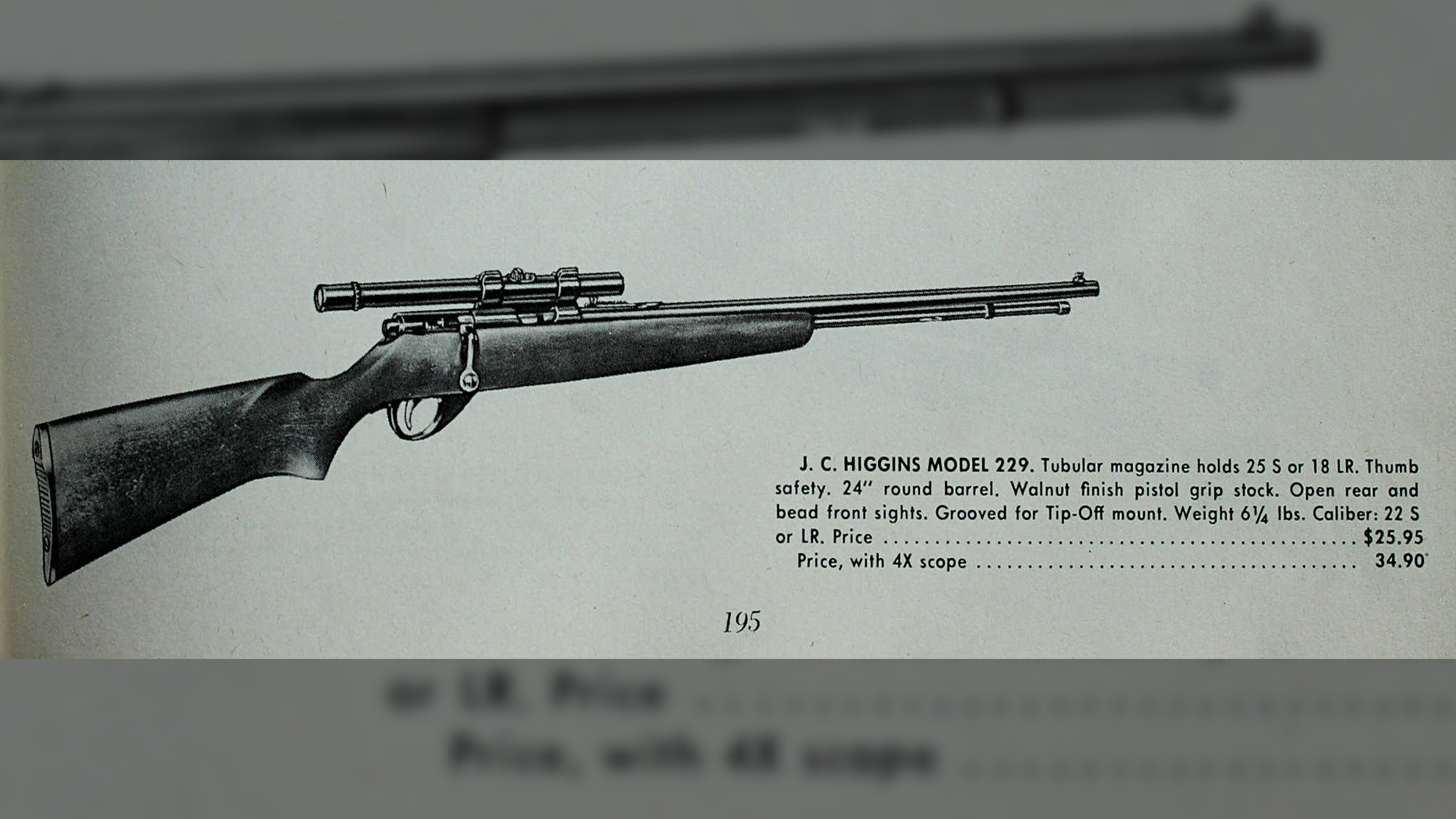

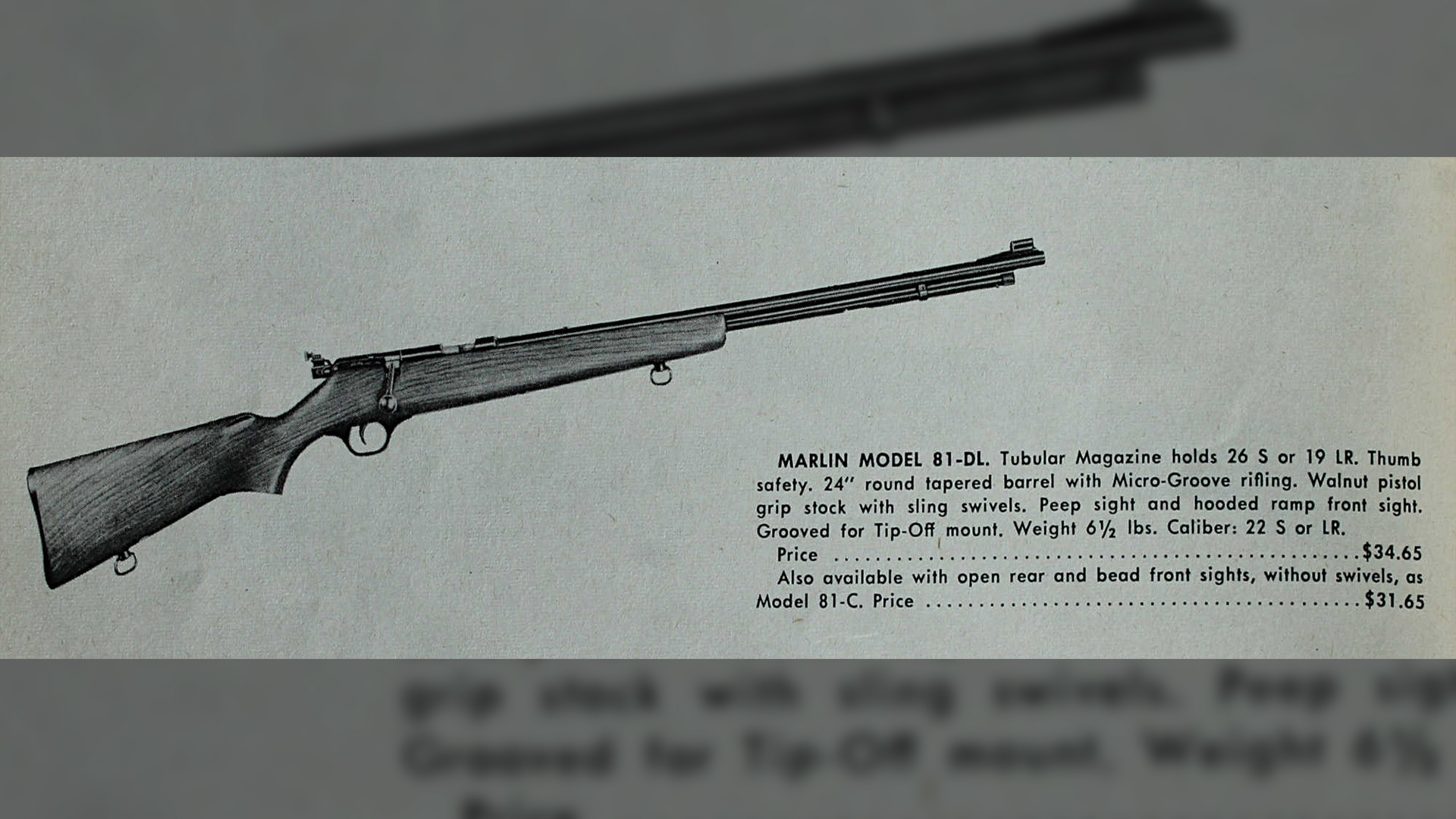

Gun Digest of 1957 lists a “J.C. Higgins Model 229;” judging from the illustration and description, it is obviously the Model 103.229. List price was $25.95, which would be about $285 in 2023 dollars. The J.C. Higgins Model 103.229 also lives a double life as a Marlin Model 81; the 1957 Gun Digest lists the Marlin Model 81-DL, with “peep sight” and sling swivels installed, for $34.65. The J.C. Higgins version has a different plastic trigger guard with a distinctive “shark fin” shape at the front and a plastic butt plate lacking a Marlin logo. The Model 81 morphed through four different bolt knob styles, which is why the receivers of the two rifles in the Gun Digest images here don’t appear identical.

With a 13-inch length of pull and overall length of 41 inches, this is an adult-size .22. Marlin (or Sears) elected to go with Marlin’s patented Micro Groove rifling in the Model 103.229’s 22-inch barrel, same as found in the Marlin Model 81. Marlin cataloged these barrels as, “Special Analysis Ordnance Steel.” This rifle’s magazine can hold .25 Short, .20 Long or .18 Long Rifle cartridges. The wood stock on this Model 103.229 has slightly more figure than a paint stirring stick; it is well-proportioned, with drop and comb suitable for either the iron sights or low mounting of a scope.

Bluing is quite good quality and still strong at nearly 100 percent. The bolt handle is bent and slightly swept backward. Marlin gussied-up the bolt handle and trigger for Sears with chrome plating. Grooves in the receiver top accept tip-off/claw mount rings.

An unusual spring steel “cartridge guide spring” above the chamber mouth engages a sloping slot cut into the top of the bolt. Its function appears to be to exert counterpressure downward on the bolt against the upward pressure exerted on the bolt by the spring-loaded cartridge guide and lifter that might otherwise cause the bolt face to strike the top of the receiver upon closing.

A chunk of the plastic butt plate is broken off this rifle—not necessarily a deal-killer, but certainly reducing the rifle’s value. A more serious problem is that the inner magazine tube was stuck immobile, eventually requiring cushioned pliers to forcibly remove it. Examination traced the fault to the outer magazine tube, which was slightly bent where it passed under the receiver. I removed the outer mag tube, and careful work with a metal rod and a hammer got it back into proper alignment. The rifle functions now and is a pleasant enough $50 plinker.

Economical deal

When checking gun values online, asking prices mean little because a great many are ignorantly or deliberately overinflated—it is the “Sold” price that renders the accurate picture. Some internet surfing turned up a few J.C. Higgins Model 103.229s that have sold online for $66 to $125; by comparison, one asking price was $475. A $35 shipping fee and $25 FFL transfer fee would add another $60 to the rifle’s real cost to a buyer. Paying a gunsmith for repairing the magazine tube and replacing the butt plate might add another $60 to $120, so fees and repairs would have exceeded the real value of this particular rifle.

The second rifle in the two-fer-a-hundred-bucks deal is a different matter, as some post-purchase research showed I scored more than expected. That’s the next chapter in Internet Economics 101 .22, which you can read next month in Part Two.