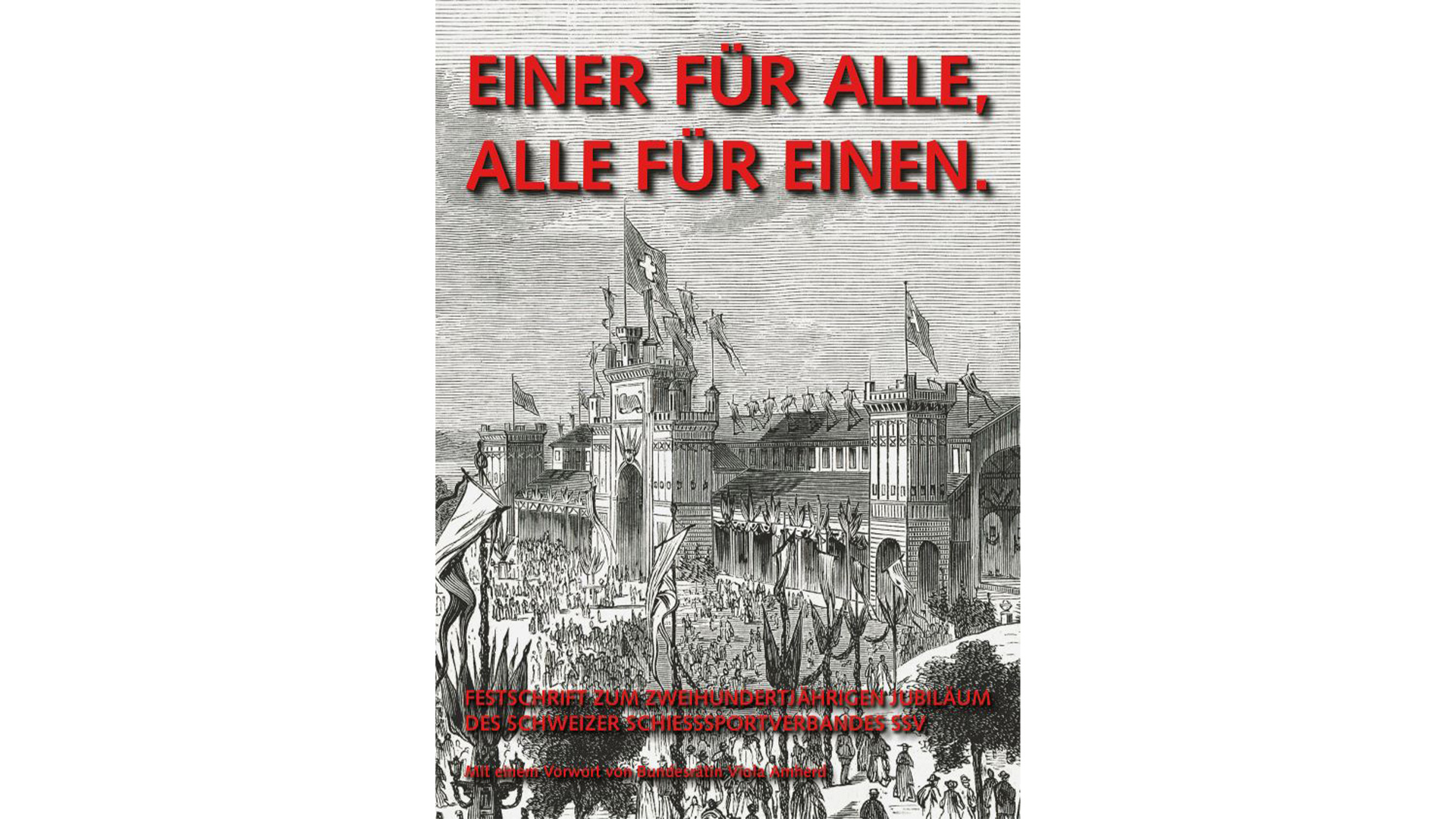

Luginbühl, Hans, ed., Einer Für Alle, Alle Für Einen. Festschrift Zum Zweihundertjährigen Jubiläum Des Schweizer Schiesssport- verbandes SSV (Effingerhof, Schweiz: Verlag Merker, 2022), CHF 69.00, hardcover, 860 pages, 978-3-85648-161-2.

In English, this title is translated as “One For All, All For One. A Commemorative for the Bicentenary of the Swiss Shooting Association SSV.” This tome does much more than celebrate the 200th anniversary of Switzerland’s marksmanship society. Given the central role of the SSV in the political, military and social life of the country, this work is also an interactive history, indeed a reference work, for those same years. This review pinpoints some of the highlights of the volume.

The book has a forward by Bundesrätin (Federal Councillor) Viola Amherd, who heads the Federal Department of Defense, Civil Protection and Sport. Six distinguished historians contribute to the tome, the most prolific is Jürg Stüssi-Lauterburg, an old friend and colleague of mine. Regula Berger, who until 2022 headed the Schützen Museum in Bern which some readers may have visited, is another contributor.

The outstanding Swiss record in international shooting competitions from 1897 onward is detailed in chapter 1. Chapters 2 through 9 describe the birth and development of the SSV shooting Organization from 1824 through 2021, each chapter devoted to specific periods of the growth of the Swiss Confederation. The roots of the rifle clubs go much further back, for instance that for Lucerne to the year 1354 and that for Geneva to 1474. But after centuries of protecting her independence by defeating some of the great armies of Europe, Switzerland was conquered by Napoleon in 1798 and did not regain her full independence until recognized as such by the Congress of Vienna in 1815. As patriotic feelings grew along with the need to establish a true armed neutrality, in 1822 Aarau rifle champion Carl Ludwig Schmid-Guiot initiated the concept of a Confederation-wide shooting association.

Chapter 2 covers 1824, when the association was actually launched, through 1849, in the aftermath of the Sonderbund War. From the beginning, the Schützenverein was tied into the military organization. The officers of the cantonal armed forces held a meeting in Langenthal that helped spark its growth in an organized manner (visit the Hotel Bären in that town today and see a magnificent mural in the hall where they met). Promotion of rifle shooting country-wide enhanced a militia force of all able-bodied men. The slogan “one for all, all for one,” originated at the Lausanne Federal Free Shooting Championships in 1836.

Chapter 3 details the development of the shooting societies in the context of the growth of the Federal Republic during 1850- 1874. Mutual participation in matches help heal divisions between the Catholic and Protestant cantons following the Sonderbund War, which unified the country while being threatened by the European governments that repressed the 1848 revolutions. Volunteer sharpshooters were organized who could defend the Confederation at a moment’s notice. A standard caliber for rifles was adopted in 1850 for marksmen who were part of the organized militia forces. The year 1872 saw the founding of the country-wide Feldschiessen, which was then and remains today the largest shooting festival in the world.

The last quarter of the 19th century through before World War I is covered in Chapter 4. The bond between the citizen and militia service was cemented by the Constitution of 1874, under which every Swiss man had the obligation to perform military service and would be given arms without charge. Regulations required the arms to be kept at home to facilitate instant mobilization. Every soldier was required to shoot a certain minimum score in the annual Obligatorische (obligatory shooting). The SSV worked hand-in-hand with the military department to promote marksmanship skills. When the German Kaiser visited to observe Swiss military maneuvers in 1912, an image of the Kaiser with a Swiss soldier entitled “in the land of the best shooters” went viral with the following dialogue:

"Also ihr seid 100000 solche Schützen; wenn nun aber 200000 Preußen kämen?"

"Dä schüsset mer grad no ä mol, Mayestät!"

("You are 100,000 fine shooters, just like you. What if I send in 200,000 Prussians?"

"Then we will shoot twice, Your Majesty!")

Fortunately, the Swiss managed to avoid the Great War through their armed neutrality, but the next period—1914 to 1939, the subject of Chapter 5—brought her up to the brink of the next war. Led by General Ulrich Wille in World War I, the Swiss militia army was mobilized to protect the borders and to prepare for attack. The SSV continued to hold matches and functioned essentially as a reserve militia. The war over, marksmanship blossomed as the one hundredth anniversary of the SSV was celebrated in 1924 with the unveiling of the Aarauer Schützendenkmal (Shooting Monument in Aarau). When the Nazis came to power in Germany in 1933, Federal Councillor Rudolf Minger, head of the military department and a strong supporter of the SSV, facilitated measures to protect the country from the German threat. The Eidgenössische Schützenfest in 1939 in Luzern would be the last of the great shooting festivals for the duration of the war. When Hitler launched World War II, Henri Guisan became head of the Swiss army, whose armed citizens would be a strong dissuasive force against invasion.

“Und Steht Der Teufel Selbst Vor’m Haus, Hier Beisst Er Einen Zahn Sich Aus” (“Should the devil himself stand in front of our house, he must withdraw with the loss of a tooth”—an old saying meaning if Satan threatens, he will lose a tooth if he attempts to crack open the fortress). The title of Chapter 6, that message was posted in a sign at the Fortress Furggels, the largest underground fortress built in Switzerland during World War II, underneath the village of St. Margrethenberg. From the fall of France in 1940 to the end of the war in 1945, the Aktivdienst (active service) generation held fast against planned Nazi invasions from the north, east and west, and Fascist invasion from the south. In addition to the troops mobilized at the borders and in the Alpine Réduit, the SSV-trained Ortswehren (local defense), consisting of 100,000 old men and boys, guarded against saboteurs and parachutists and formed a cadre of armed resistance. This was not a time for matches—most men were on duty, and ammunition was in short supply—but a time for being on constant alert. While completely encircled by the Axis, the Swiss held firm. Winston Churchill said near the end of the war: “Of all the neutrals, Switzerland has the greatest right to distinction.”

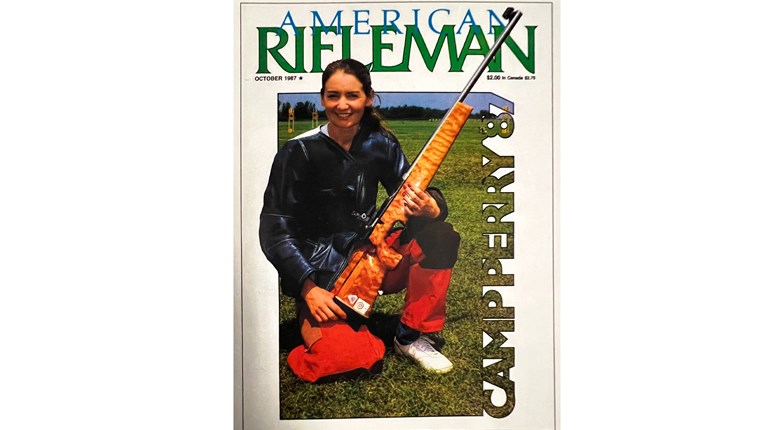

The Cold War from 1946-1970 is the subject of Chapter 7. In 1946, more than 460,000 competitors shot rifle matches. Soviet aggression in Eastern Europe continued the serious and civic purposes of the SSV shooting programs. These years saw an increase in participation of women in shooting. As throughout the book, presidents of the SSV and their contributions are described.

SSV membership in 1971 amounted to 500,000, falling to 200,000 by 1999, as noted in Chapter 8. The fall of the Berlin Wall and the dissolution of the Soviet Union greatly eased tensions to the extent that required military service also fell in this period. Symbolic of the times was the initiative brought by the Group for a Switzerland Without an Army, which was voted down in 1993. The Eidgenössische Schützenfest in Thun in 1995 fielded 72,241 participants (yours truly being one). The world was changing.

“The shooting tradition embodies one of the basic values of our country,” according to Bundesrat Ueli Maurer, a member of the Federal Council, where he served as President twice. His tenure is described in Chapter 9, which covers the years 2000-2021. In 2011, the Swiss rejected the Waffendiktat initiative that would have banned soldiers from keeping their military weapons at home, but in 2019 voted in favor of a Schengen-induced referendum that imposed European Union restrictions on firearms. While Covid caused the cancellation of the Federal Shooting Festival in Lucerne in 2020, it was held the following year. Life has returned to normal, in the shooting world as elsewhere.

While the entire book is well illustrated, Chapter 10—on the Schützen Museum in Bern—is lavish. After a print of the Federal Shoot in Bern in 1885—the year when the concept of the museum originated—the reader is treated to color photographs of trophies, medals, paintings, historic posters and glass art. The stairway walls are filled with scores of small arms, showing the historical development from crossbows and matchlocks to flintlocks and modern cartridge rifles.

The great hall upstairs houses the collection. (My only regret is that the two large paintings of bears enjoying a shooting festival is not included.) The museum’s building, completed in 1939, is located behind the Bernese Historical Museum, and its outer facade features an enormous painting of soldiers, citizens, and youngsters with rifles and the national flag.

The “Haus der Schützen” is a beautiful mansion owned by a foundation with that name located at Lidostrasse 6 on the Lake of Lucerne. Built in 1918, it was acquired by the foundation in 1960. It hosts SSV functions and houses administrative offices. Its history, which unfortunately has included periodic flooding from the lake, is described in Chapter 11.

Chapter 12 traces the evolution of Swiss arms from 1824 to today. Cantonal arms gave way to standardized federal arms in 1847 and thereafter. When first issued in 1869, the Swiss Vetterli rifle was the most modern military design in the world—it held twelve metallic cartridges in its tubular magazine at a time when most armies still used single-shot rifles requiring a manual reload after each shot. The 1889/96 and 1911 Schmidt-Ruben bolt-actions came next, using the 7.5 mm cartridge with smokeless powder.

That was replaced by the Karabiner 1931, which was issued until 1958. The age of the Sturmgewehr (assault rifle) arrived with the heavy Model 1957 and then the lighter Model 1990, today’s service rifle. These last three models are in wide use in competitions today, along with the SIG 210 pistol, the most accurate 9 mm pistol in the world.

As the Schweizer Schiesssportverbandes enters its third century under the leadership of its current president, Luca Filippini, it will surely face dramatic challenges as elements of popular culture discourage patriotism and marksmanship, European Union diktats demand civilian disarmament, and terrorism and unprovoked aggression threaten peace and freedom.

Stephen P. Halbrook, Attorney at Law, is author of "Target Switzerland" and "The Swiss and the Nazis." Go to stephenhalbrook.com.