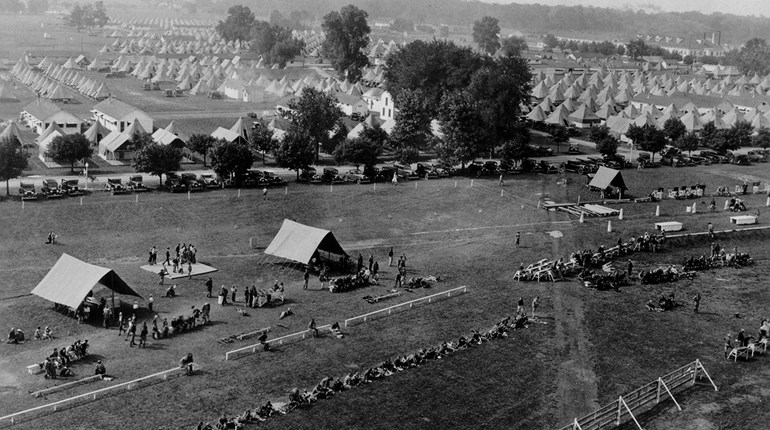

Above: George Farr and his ’03 Springfield pose in front of his Camp Perry tent in the competitor bivouac area.

It was 1921. Warren G. Harding was President; WWI was barely three years in the past and the Emergency Quota Act had recently been enacted limiting the number of immigrants admitted into the United States. On September 9 of that year, a 62-year-old man dressed in a khaki shirt and dungarees strode up to the firing line, rifle in hand. It was George Farr’s first time at Camp Perry and perhaps things were not going as well as he would have liked. The 1903 Springfield service rifle he had drawn the day prior had problems holding its zero and now he was preparing to fire from the 1000-yard line with a replacement gun he had never shot before at that distance.

Fellow shooters on the line may also have wondered about this tall Washington State resident’s choice of spotting scope. Farr had fashioned a crude monocular by cutting a pair of French opera glasses in half. But many of the other competitors were too tired to speculate. After all, it was 4:30 pm, the last relay of the day and the light was starting to fade. Farr loaded his rifle with a clip of five rounds and began to fire. His choice of ammunition was government issue, loaded at Frankford Arsenal and fitted with tin-plated projectiles to limit barrel fouling. More experienced shooters on either side of Farr were using commercial Remington match ammunition like the master shooters of the day, including Marine SGT John Adkins, who had just won the Wimbledon Cup with this ammo. Farr’s first sighting shot was high in the three ring and probably a few bystanders were surprised that this tyro, a man who shifted repeatedly in his prone firing position between shots, had even managed to get on paper.

Farr loaded his rifle with a clip of five rounds and began to fire. His choice of ammunition was government issue, loaded at Frankford Arsenal and fitted with tin-plated projectiles to limit barrel fouling. More experienced shooters on either side of Farr were using commercial Remington match ammunition like the master shooters of the day, including Marine SGT John Adkins, who had just won the Wimbledon Cup with this ammo. Farr’s first sighting shot was high in the three ring and probably a few bystanders were surprised that this tyro, a man who shifted repeatedly in his prone firing position between shots, had even managed to get on paper.

But Farr continued to shoot at the 36-inch bullseye, firing his second sighter, followed by twenty rounds for record. With a sight adjustment in response to his first sighter, the next twenty-one shots had all been bullseyes. Being new to competition procedures, Farr gathered his equipment and prepared to depart the firing line. One of the range officers quickly stopped him and explained that match rules called for a shooter to continue firing until they missed the “black” (bullseye or 5-ring) of the target. Farr was happy to comply and to continue shooting, but first he would need more of his tin-plated ammunition, spurned by the other shooters. He patiently waited while more ammunition was retrieved. Time passed and the relentless sun dipped even lower.

A new supply of ammunition having been found, Farr began firing again in a race against the twilight. From time-to-time, he’d pause as his target was pulled for scoring, only to snap back into readiness as the carrier and target returned. The string of bullseyes continued with 30, 40, then 50, and now 60 consecutive 5’s being carefully recorded on Farr’s scorecard. A crowd had gathered, but the growing darkness made the difference. Farr’s 71st shot for record went out of the black. Counting his second sighter, he had fired an incredible string of 71 consecutive bullseyes, all with government-issue ammunition and a rifle he had just picked out of an Army ordnance rack that day.

Admiring shooters surrounded George on all sides and it wasn’t long before someone suggested that the rifle and its shooter deserved to stay together. A collection taken up from fellow competitors representing several state teams made it possible for Farr to purchase that rifle. A silver plate for the left side of the rifle was engraved to commemorate the event. But the story doesn’t end there.

The next year, the Civilian Team Trophy was re-designated as the Farr Trophy. George Farr’s record string on the old target system was never beaten.

Ninety years later, the Farr family wanted to have this rifle displayed in the National Firearms Museum and made a donation of the rifle and the monocular that Farr had used back in 1921. The items now rest quietly in the Camp Perry exhibit. Close by is the silver silhouette of the Farr Trophy, together again.