We have many tools to assist us in handloading consistent precision ammo―scales, trimmers, neck turners, reamers, chamferers, primer pocket uniformers, flash hole bevelers, comparators, collet dies and more―but annealing has been an imprecise practice, if we bothered to do it at all. From New Zealand we now have the AMP, an acronym for “Annealing Made Perfect,” referring to both the machine and the company that makes it, who are changing annealing from home-brewing to near rocket science.

Heat and hassle

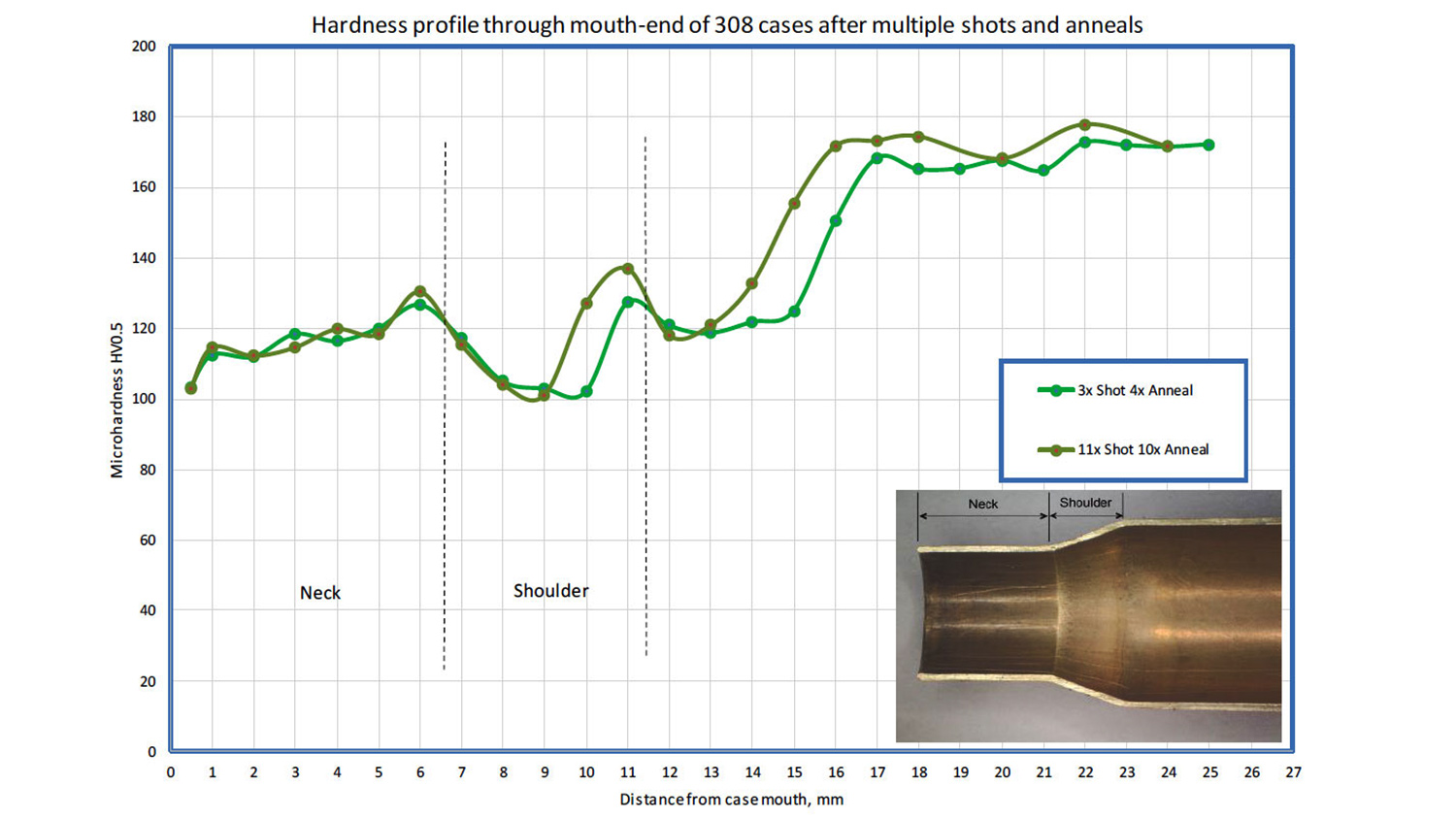

Looking at a brand new factory case we can usually see a blue-tinged discoloration in the neck/shoulder area. This is caused by the factory heating the brass in that area after forming the case in order to soften it so that it can expand upon firing to seal the front of the firearm’s chamber. When we repeatedly shoot and resize cartridge cases, the brass in the neck/shoulder area becomes “work hardened” from flexing back and forth under those stressors and eventually fails as a crack or split in the neck or shoulder. In our context, annealing refers to using heat to re-soften that work hardened brass area so that it is malleable again.

Home brew annealing consists of standing up cases in a pan of water (to prevent softening the brass of the lower part of the case), heating the neck/shoulder areas with a propane torch, and tipping the cases over into the water (to cool them for handling―there is no metallurgical benefit, as in quenching heated steel). While it does work, the procedure is obviously lacking in precision and consistency. It’s also, speaking from experience, a time-consuming pain in the patootie. Its real, practical application is perhaps less in the field of precision shooting and more about simply getting the most reloads from cartridge conversions and from expensive, obsolete brass cases before they suffer neck or shoulder splits.

But annealing benefits precision shooters too, in providing consistent neck tension on bullets for more consistent velocity, equating to smaller shot groups. The key words here are “precision” and “consistency,” and we aren’t going to get that from the pie-pan-and-torch method, especially compared to utilizing the computer-controlled annealing of the AMP.

Creating consistency

The AMP annealer works without an external heat source, instead utilizing magnetic fields to heat the brass in a process called induction heating. Keeping an explanation as simple as possible, in the AMP standard house current powers electromagnets, the magnetic fields of which oscillate at high frequency. Insert a brass case into the rapidly oscillating magnetic fields and they create an eddy current inside the brass; the resistance of the brass to the eddy current causes the brass to heat.

It’s the same principle that makes a kitchen induction stove heat pots and pans. The trick with precisely annealing brass cartridge cases is to create exactly the right amount of heat in only the neck/shoulder area, and the reason precision is tricky is that not all brass is made to the same thickness, nor of exactly the same composition (brass is roughly 70 percent copper and 30 percent zinc).

For this reason the AMP annealer is computer controlled and very specific to a particular manufacturer’s cartridge case―and sometimes even to a specific lot number. AMP has spent and still spends considerable time and effort in testing thousands of cases so that users can program their AMP annealer to those specific cases. The software is built into the AMP annealer, and reprogramming by the handloader consists of simply punching in a predetermined setting as a number on the machine’s visual display. AMP provides a lengthy list of specific factory cases and settings to the user, but consider that neck turning or reaming changes the geometry of cases and their response to electromagnetic field intensity―remember, we’re talking in scales of ten thousandths of an inch down to essentially a molecular level. To precisely anneal cases, it’s necessary to send samples to the company for analysis so that AMP can provide the user the best program for their cases. AMP analyzes cases at no cost to the customer (beyond shipping) and adds that new program to its expanding list available online to all AMP annealer users. A USB cable provided with the AMP allows the user to download new programs from their home computer into the AMP machine.

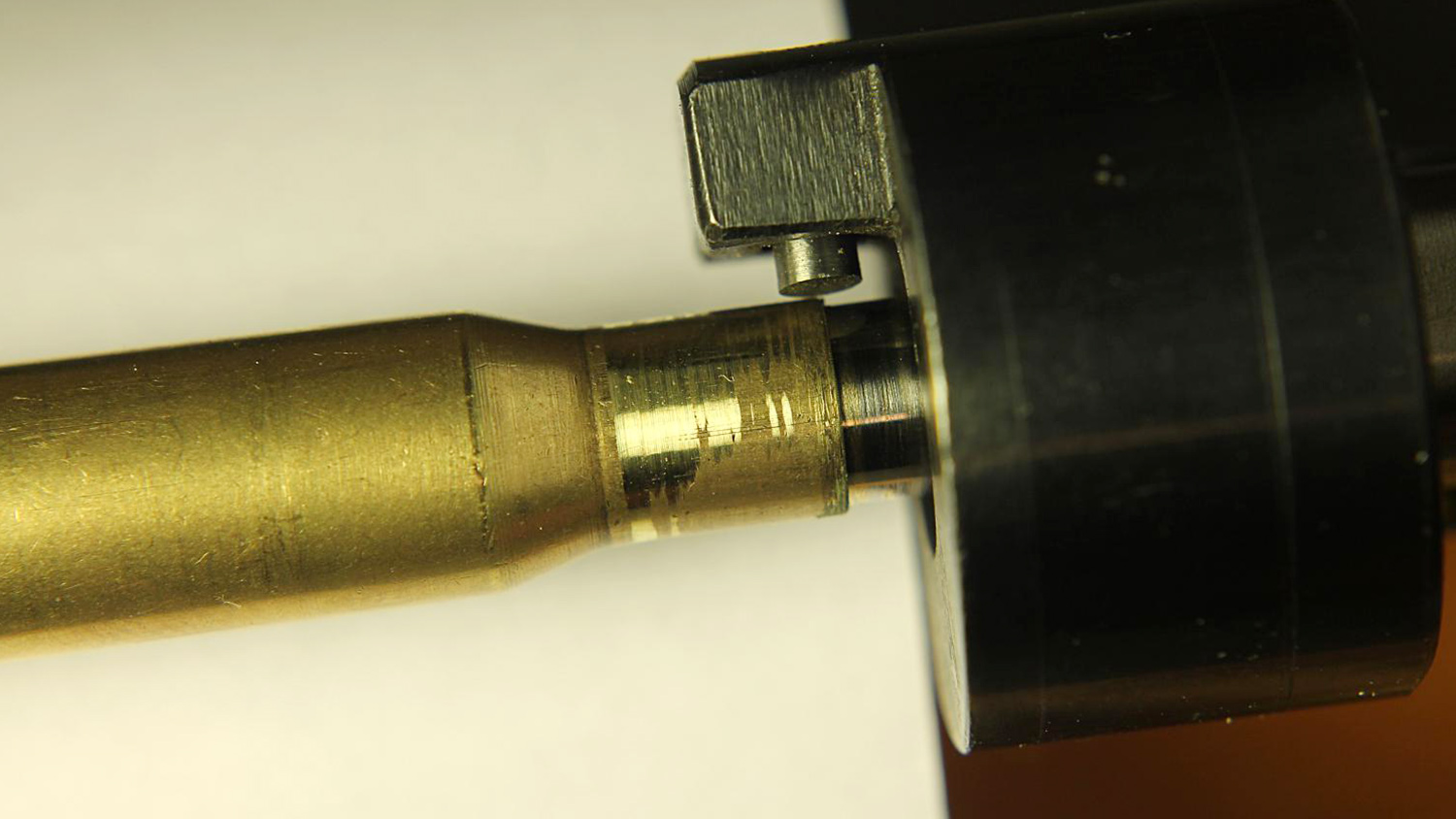

Annealing is simple and fast. Install the proper pilot for your cartridge case, select the program number, insert the case, press “START” and withdraw it a few seconds later when the START light extinguishes. Done. Dropping the just-annealed brass onto a damp rag will cool it in a few moments for handling.

Benefits

Okay, now we come to the cost/benefit analysis, always difficult because one factor, the cost, is a constant and the other factor is a variable that only you can plug in. Yes, annealing can get more loadings from a case, which equates to a cost savings over time. How much so depends entirely on how many cases are involved. There’s also a capitalist potential in recouping some cost in annealing cases for other handloaders. It has the potential to become a new niche cottage industry. And a gun club that purchases an AMP annealer to loan or rent can spread that shared cost among its members.

The convenience of an indoor tabletop annealing process is undeniable―no dangerous propane torches, no setup of cobbled-together pieces, just plug and play. And computer control means annealing is absolutely precise and with a consistency impossible with the home brew method.

The AMP can fine tune our load another step for more confidence in our ammo, and it can shrink groups several percentage points. In this regard, the AMP may benefit Bench Rest shooters more than the rest of us, but who would settle for ¾ MOA ammo if they could have ½ MOA ammo?

Beyond competition, for those who delve into cartridge conversions or those who buy four-dollar-apiece custom made obsolete brass, the AMP can extend the life of work intensive or expensive brass. Same goes for those who shoot full-throttle, long range cartridges and who reload big, $5-from-the-factory “Cadillac” cartridges like the Weatherbys and Lazzeronis.

Shooting results

Now let’s get to the bottom line for Vintage Military Rifle competition shooters: does annealing give us smaller groups? That’s a difficult definitive without shooting thousands of rounds under ideal conditions (a vacuum would be nice), but the practice in other shooting disciplines supports the theory. Many others, including Bench Rest shooters, have already tested the theory and provided AMP with testimonials you can read at the AMP website. Rather than follow their footsteps of uber-optimizing bench rest handloads, I thought I’d ask, “Can the AMP annealer make a silk purse from a sow’s ear?”

Here, the sow’s ear is Greek milsurp brass from M2 Ball .30-′06 made in 1976, “HXP 76” headstamp. I turned necks to a uniform thickness―a requirement for precise annealing―and sent sample cases to New Zealand for AMP’s analysis from which they derived an appropriate program for the machine. In a nutshell, two groups each fired from my M1903A4 Vintage Military Sniper Rifle competition gun and measured with a caliper averaged like this:

Out-of-the-can HXP 76: 2.95″

Once-fired, no match prep, annealing only: 2.74″

Fired 3x, no match prep, no annealing: 3.36″

Fired 3x, match prep, no annealing: 2.65″

Fired 3x, match prep, annealed: 2.70″

The load I quickly made up specifically for testing this brass is 57-grain IMR 4831, Fed 210M primer, Hornady 150-grain FMJ. Match prep consisted of trimming and chamfering, primer pocket uniforming, flash hole beveling and the requisite neck turning. The rifle is inherently capable of 2 MOA. Distance was 100 yards.

Conclusions and caveats

Sow’s ears don’t become silk purses from annealing alone, and we didn’t expect that they would. Though it might appear that annealing could be a substitute for match prepping cases, that is unsubstantiated without shooting many, many more groups, and no one has ever made or now makes that claim. Still, it’s an interesting comparison. From this tiny sampling we note that it appears we can reload 3 MOA factory HXP 76 to make sub-3 MOA groups, but even 2 MOA is probably not small enough to detect whether annealing shrinks groups. The only further confident conclusion we can make here is that we need more data to make any further confident conclusions.

Again, this was a test conducted out of simple curiosity, which is one of the reasons we handload, yes? Shooters all over the planet utilizing more precise rifles and handloads and firing over longer distances have contributed mountains of data and testimonials indicating the AMP annealer does, indeed, shrink groups by providing more consistent neck tension on bullets.

Better yet, the AMP moves annealing from, “Oh, brother” or “It ain’t worth it” to, “Sure, I’ve got a few minutes.”

Purchase the AMP annealer from Brownells for $1,100