The world’s first “high capacity magazine” rifle isn’t a semi-automatic—it’s a lever-action rifle that held 34 rounds and served in warfare in the late 1800s. Today, the Evans Repeating Rifle is one of the more enigmatic among early repeating American arms, though it was once common enough that Winchester was still manufacturing .44 Evans Short cartridges into the 1920s.

Maine dentist Dr. Warren R. Evans gets credit for inventing the Evans Repeating Rifle, though his brother George, a machinist who owned a farm equipment factory in Norway, Maine, was also involved. The first incarnation of the Evans Repeating Rifle, later referred to as the Old Model, was quite amazing in 1874 for boasting a magazine capacity of 34 rounds. Loaded through a gate in the butt plate, the tubular magazine running the length of the buttstock fed cartridges in helical fashion with each cycling of the underlever, and a shooter could empty the magazine in 20 seconds of aimed fire.

Military Failure

The intent of the design was to appeal to the US Army. Though its advantage over the US Army’s single-shot .45-70 Trapdoor rifle is seemingly obvious, the .44 Evans cartridge suffered acute anemia; being only about as powerful as a 9 mm Luger pistol round, it had less than a quarter the muzzle energy of the .45-70. The US Army declined the Evans Repeating Rifle and cartridge. Russia, Turkey and Peru were the only governments to purchase Evans rifles. The Evans saw action in the 1879-1884 Saltpeter War between Chile and a Peruvian-Bolivian alliance fighting—to oversimplify—for possession of real estate rich in bird poop, a then-valuable source of saltpeter (potassium nitrate), used in making gunpowder and fertilizer. The Evans’ “high capacity magazine” rifle was not enough to tip the war in Peru’s favor.

Refused by the US Army, the Evans Repeating Rifle Company turned to the commercial market in 1874, manufacturing rifles at Mechanic Falls, Maine. The company made about 500 rifles between 1874-1876. By the next year, George Evans had made several improvements to the rifle, and the cartridge case was lengthened to create the more powerful .44 Evans Long cartridge. This improved rifle became the New Model, and the original became the Old Model. “Unsolicited testimonials” in a period advertisement claims the Evans outshot the Sharps, Winchester and Ballard rifles in competition. The most outrageous supposed claim was, “I have shot Sixty Buffaloes at a run, and pennies from between my wife’s fingers at 40 paces.”

Ultimately, Evans manufactured about 12,000 Sporting Rifle, Carbine and Military Musket models before going bankrupt in December 1879. Failure was perhaps due more to the comparatively weak Evans cartridge, than to the rifle itself. For more information about the company, visit the NRA Museum website.

Not Hammerless

With an overall length of 39 inches and weighing 8½ pounds empty, the Evans New Model Carbine here has a bit more heft than comparable lever guns with similar 22-inch round barrels. The sole marking is, “EVANS REPEATING RIFLE MECHANIC FALLS, ME PAT. DEC. 8 1868 & SEPT. 16, 1871” stamped into the barrel. Three steps on the rear sight base, marked, “1,” “2” and “3,” evidently represent 100-yard increments as the sight notch assembly slides forward to engage the steps. Flipped up, the sight ladder is graduated out to 1,000 yards.

Receiver and magazine tube are split lengthwise into left and right halves secured to each other with five transverse receiver screws. One of the five screws also serves as a pivot pin for the lever and the ejection port cover, and another as the trigger pivot pin. The receiver top bears deliberate, circular machine marks applied, apparently, as an anti-glare measure. The marks on the left half of the receiver are longer than on the right half, indicating they were applied before the two receiver halves were screwed together.

Despite its appearance, the Evans is not “hammerless.” The hammer is the longer of the two protrusions below the front of the lever, sliding downward to cock when the lever is operated, and sliding upward to strike the centerfire cartridge primer. The hammer can also be cocked by pulling it downward. The shorter protrusion in front of the hammer, when engaged into a notch in the hammer, locks both lever and hammer, but only when the action is not cocked, so it does not act a safety.

Buttstock wood is in two pieces, upper and lower, protecting the magazine tube. A screw through each half threads into a band surrounding the magazine tube about midway between butt plate and receiver, and butt plate screws provide additional support.

.440-inch?

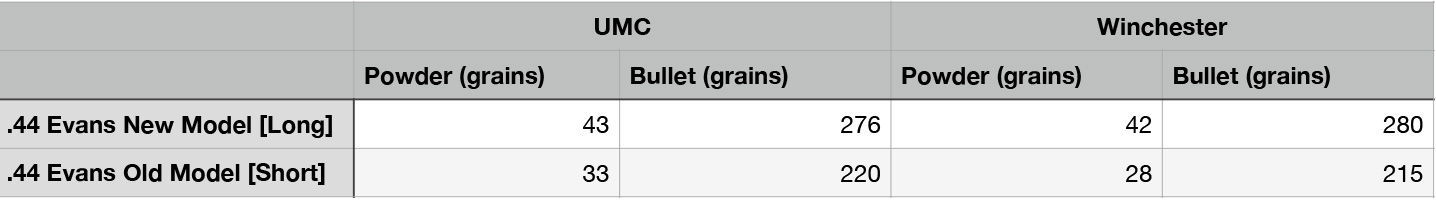

Several sources report it is possible to fashion .44 Evans Long cases from .303 British, .303 Savage, .38-40, .30-40 or .445 Super Magnum brass. Like the .22 Long Rifle cartridge, the centerfire .44 Evans utilized a heel-base bullet. Cartridges (Herschel C. Logan, Standard Publications, Inc., 1948) reprinted this information from an 1890s catalog listing these black powder loads offered by UMC and Winchester:

Exact bullet diameter, however, is harder to pin down. As with many .44 caliber cartridges, the .44 Evans Long is apparently not actually .440 inch in diameter. One 1985 source reprinted online reported his Evans bore measures .431 inch; Donnelly (The Handloader’s Manual of Cartridge Conversions, John J. Donnelly, Stoeger Publishing Company, 1987) lists .434 inch as neck diameter for the .44 Evans Long and .439 inch for the Short version. Ammo Encyclopedia 6th Edition (Michael Bussard, Blue Book Publications, Inc., 2017) says bullet diameter for both cartridges are the same .419 inch.

Still Around

New Model Evans rifles and carbines crop up fairly regularly at online auction sites, with guns the past several years selling for $896 to $2,995, depending on condition and features, though asking prices run upwards to $4,500 for ordinary guns and into five figures for special factory presentation rifles. In about NRA Antique Good to Very Good condition, the example here is worth perhaps $1,500 to $2,000.

There are still enough Evans Repeating Rifles around that a patient and diligent searcher with advanced handloading skills could undoubtedly score a “shooter.” But if you believe it will outshoot a single-shot Ballard, Sharps or Winchester in competition, I’ve got some Arizona beach front property to sell you.