Admittedly, when I first heard about calling your shot, I had no idea what it meant and why it was so important to do so. The only other time I’d heard the phrase was when shooting pool. In pool, a player that is calling their shot is broadcasting what they are about to do. In shooting, it’s nearly the complete opposite, as you’re telling yourself and your spotter where the round went after you fired, without being able to see the impact on the target. I introduce the concept to my students by telling them, “It’s okay to miss, just as long as you can tell yourself how you missed and eventually learn what you need to do to stop the issue.”

Being able to call your shot marks a major milestone in a shooter’s progression. When someone starts shooting, the event of firing a gun can be extraordinarily overwhelming. New shooters are fixated on the gun, the recoil and, of course, the noise. The gun goes bang, both eyes close briefly (sometimes far longer than just a blink), the gun recoils violently and accuracy is measured in hits on paper or hits off paper. As time goes on, that same shooter will learn to better manage recoil, become comfortable with the noise level and the gun will have no more novelty than any other hand tool that they may encounter in daily life. Once all of those distractors are eliminated, the shooter can now pay closer attention to what they have done when they pressed the trigger, and keep a better eye on the front sight to detect movement as the shot broke.

Shooters don’t need to be taught to call their shots, they just need to be made aware when they have become proficient enough to do so. This is my favorite turning point with a new shooter. When they turn to me and say, “I really yanked one.” I remind them that they had no comprehension of that when they first started shooting, and that acknowledging a poor trigger press indicated that they understand what a good press is.

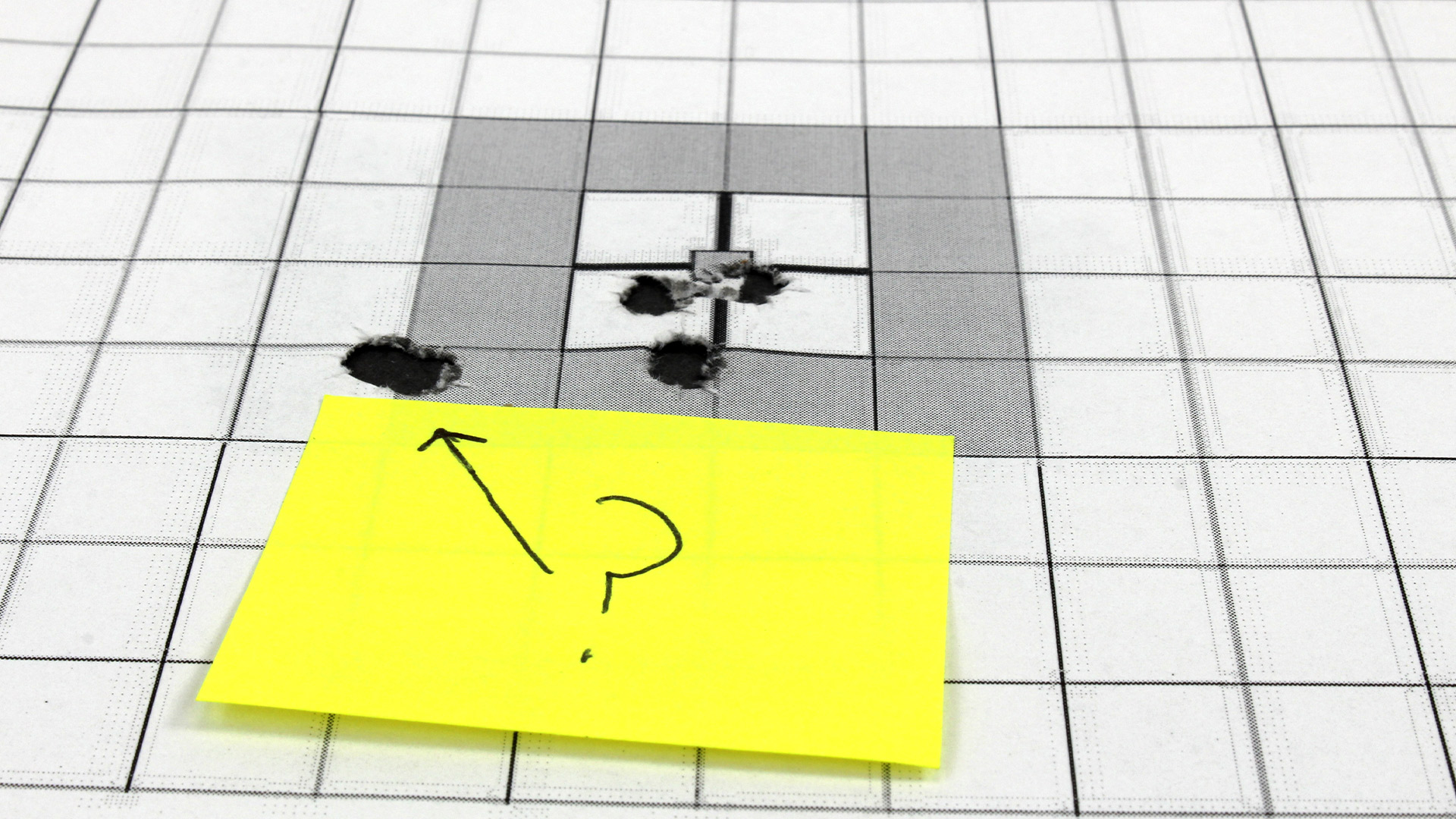

Now, reading their targets? That’s another story, and the two skills must be mastered together to spot errors and apply corrective actions. If you’ve seen “The Pistol Shooter’s Wheel of Misfortune” then you already know that the clock position of your shot can tell you a bit about what you are doing wrong. Although the wheel isn’t perfect, it plants the seed for what to look for when your shot breaks. A shooter who is using too much trigger finger is likely to push their shots to their weak side, while a shooter who flinches will also push a shot to that side, but it will be much lower. Did you attempt to double-tap a target and your first shot is on but your second one off? That is likely a case of poor follow-through, and so on. As shot inconsistency is infinite, so are diagnostic and corrective measures. However, one aspect that is simple to read and consistent to work with is sight picture. If a shooter is focusing on their sight, reticle or dot, they are applying correct technique—and can also tell where it was when the shot touched off. No coaching is required in that scenario.

While the previous paragraph speaks to practical, or speed-based shooting, being able to call your shots is equally important in a precision application. For instance, zeroing a rifle. A few of my buddies RSO at a public range, and every October, they clean house in tips simply by helping new hunters zero their rifles. These shooters may understand their click adjustments, but often are applying those clicks to a group that was produced through pure shooter error. You can imagine their frustration when the “group” moves to a completely unpredicted quadrant of the target. Now, that’s a tough problem to have at 100 yards, but imagine adding another 500 yards of distance. Precision long-range shooters must be able to call their shots so that they can differentiate between a miss caused by wind, a bad trigger press or poor support.

The last group that I want to speak to are those that craft their own ammunition. Handloaders will benefit from this self-awareness, because they will be able to determine if a shot that opens up a load development group is an issue with the round or just poor shooting fundamentals. This will help keep them from dismissing a stellar load that was simply shot poorly, not to mention countless hours at the loading bench chasing something that was there the entire time, they just weren’t able to see it.

Keep shooting

So how do you get to the point where you can call your shots? Simple, just keep shooting. The fundamentals of sight alignment, sight picture and follow-through will all lead you to this point—it just takes patience. Mitigating any factors you find unpleasant involved with firing a gun will help expedite the process a bit, too. Spend more time shooting rimfire or if your state and budget allow, install a suppressor onto your firearm. Reducing the noise will help you keep your eyes open to see what is going on. Also, never underestimate the value of the ball and dummy drill. When the hammer drops on a dummy round (that you weren’t expecting), your body will do the exact same thing that it does when the gun goes bang, except this time your movement won’t be covered up by the recoil.

Regardless of which methods you decide to employ, be sure that you are learning a little more about yourself with each shot that you send downrange. After all, if you aren’t learning when you are shooting, all you are doing is turning money into noise.

Read more: Closing a Match