WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

If you’re a savvy shooter, you have certain expectations from the gun you buy. You select the caliber and size, and you know that longer barrels produce more velocity. The latter is generally true, but there are exceptions because every barrel is different. (I described an example of this in a previous article about semi-automatic pistols.)

But, with revolvers, it can be even more extreme. I have one revolver that’s best described as “slow” because it does not produce the speeds that it should.

A general rule is velocity will vary by about 50 f.p.s. for every inch of change in barrel length. This depends on the powder and if you’re working with short barrels.

The .357 Mag. revolvers in my collection have barrel lengths ranging from 1.88 to 8.38 inches. Most of them produce velocities as to be expected for their barrel lengths; however, one does not.

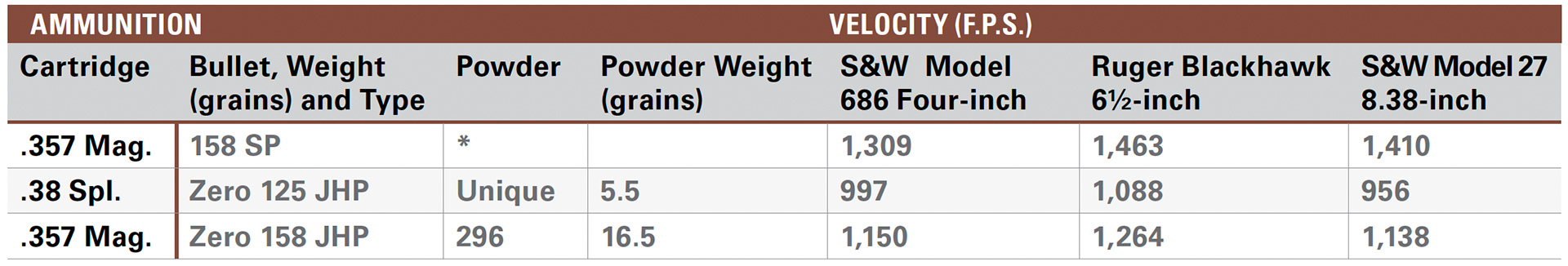

When testing Remington .357 Mag. 158-grain soft-point ammunition, my fourinch Smith & Wesson Model 686 produced an average speed of 1,309 f.p.s., which is quite a bit higher than its advertised 1,235 f.p.s. speed. This is not unusual for Remington .357 Mag. ammo, which can run faster than its published speed. My Ruger New Model Blackhawk 6½-inch barrel produced an average of 1,463 f.p.s., a 154 f.p.s. increase over the four-inch barrel. My Model 27 with 8.38-inch barrel produced an average speed of 1,410 f.p.s. I was expecting a speed of around 1,550 f.p.s. or more from this barrel length, but it was only 101 f.p.s. faster than the four-inch barrel and was 53 f.p.s. slower than the 6½-inch barrel—not good.

I ran more tests to confirm the speed disparity with two handloads. With these loads, the 8.38-inch barrel was slower than the fourinch barrel. The .38 Spl. load ran 997 f.p.s. through the four-inch gun, 1,088 f.p.s. through the 6½-inch gun, and a paltry 956 f.p.s. through the 8.38-inch Model 27, 41 f.p.s. slower than the shortest barrel.

The .357 Mag. load was clocked at 1,150 f.p.s. through the four-inch Model 686, and 1,264 f.p.s. through the 6½-inch Ruger, and 1,138 f.p.s. through the 8.38-inch Model 27. Here, the longest barrel was 12 f.p.s. slower than the four-inch barrel.

My 8.38-inch gun’s slow speeds might make you think there must be something wrong with it, but it’s well known that revolvers can produce different speeds—even when comparing the same ammo in the same brand, model and barrel length of gun. While slow velocities are not what I hoped for, it’s not unusual for some revolvers to be slow.

Chapter 18 in “Speer’s Handloading Manual No. 14” (circa 2007), titled “Why Ballisticians Get Gray,” was written by David Andrews (writer and producer of Speer manuals six through 11) and originally published in “Speer’s Handloading Manual No. 9” in 1974. This chapter lists ballistics from 26 individual .357 Mag. revolvers made by Colt, Dan Wesson, Ruger and Smith & Wesson of differing barrel lengths. They had duplicate guns with the same brand, model and barrel length of many guns they tested.

Some of the velocity differences were pretty wide between identical guns. For example, of three Colt Pythons with six-inch barrels, the slowest speed with their 158-grain load was 1,002 f.p.s., and the fastest speed was 1,251 f.p.s., which is a 249 f.p.s. difference from the same barrel length. The 1,002 f.p.s. speed is certainly slow. Two out of three of their revolvers with 2½-inch barrels produced faster speeds than that with the same ammo. The identical guns weren’t all oddballs, and many recorded speeds were close to one another.

Differences in chamber and barrel internal dimensions can affect velocity. One important characteristic for revolvers is the barrel-cylinder gap. How wide that gap is determines how much gas escapes through it, and the more gas that escapes, the more pressure that is lost. More pressure loss means the bullet won’t go as fast, because there is less pressure pushing it.

Remington noted in its 1976 Law Enforcement catalog that you can vary the velocity of .38 Spl. ammo by about 12 f.p.s., and .357 Mag. ammo by about 17 f.p.s. for every 0.001-inch the gap changes.

The gap on my four-inch Model 686 is 0.004-inch, on the 6½-inch Ruger it’s 0.005-inch, and the gap measures 0.011-inch on my 8.38-inch Model 27. Regarding the latter, the wider barrel-cylinder gap certainly could contribute to its low speeds. Using Remington’s numbers, if the gun had a nominal gap of 0.005-inch, it would gain 102 f.p.s. (6 x 17 = 102) with the Remington .357 Mag. ammunition I used. That would get it to 1,512 f.p.s., closer to my estimated 1,550 f.p.s., but still shy by a measurable margin. Looking at the data from the handloads, the Model 27 is about 200 f.p.s. slower than one would expect for that barrel length (50 f.p.s. per inch of barrel length), since it was not faster than the four-inch barrel.

While the barrel-cylinder gap is a good candidate for causing the slower-thanexpected velocities, there are probably other factors that contribute to it. After all, semiautomatic barrels can also show unexpected differences in speed, and they don’t have a gap to blame it on.

This Model 27 is simply slow. Other guns are as well, which Speer notes in its handloading manuals. It happens, and the nice-looking Smith & Wesson revolver will remain in my collection.