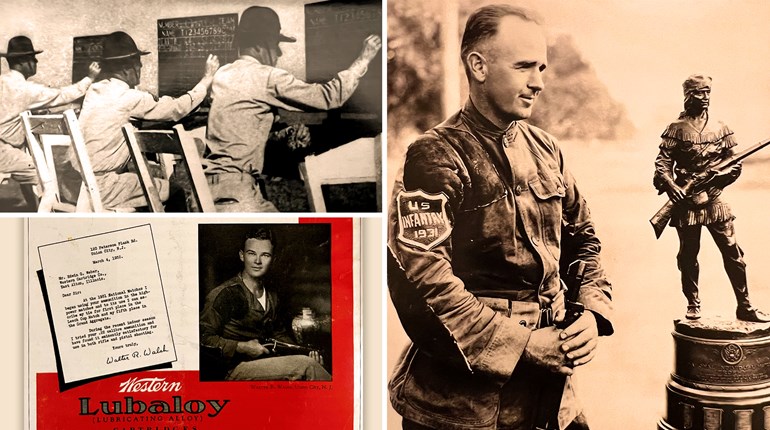

From the August 1956 issue of American Rifleman, an introduction to competitive pistol shooting by Lt. Col. Jim Crossman.

If you’re looking for some tips on how to make a fast draw, then you’re in the wrong place. This article has to do with that fine and fast-growing competitive game—pistol shooting. It’s a most pleasant pastime, requires relatively small range space, no great physical strength or physical effort, and it is only as expensive as you want to make it.

The courses

The U.S.-developed pistol game is all related, in one way or another, to the three-stage National Match Course (NMC). This NMC consists of a 10-shot string slow fire at 50 yards—10 shots in 10 minutes; two five-shot strings of timed fire at 25 yards—20 seconds for each five-shot string; and two five-shot strings of rapid fire at 25 yards—only 10 seconds for each string. The target is the same for all three stages, but at 50 yards the eight, nine, and 10 rings are black, while at 25 yards only the nine and 10 are black.

Both the Camp Perry Course and the NRA Short Course are three-stage events fired at 25 yards range. Both these include timed fire and rapid fire stages as in the NMC, and differ only in the slow fire stages. In the Camp Perry Course, slow fire is shot in two five-shot strings, 2 ½ minutes for each string, on the 25-yard timed and rapid fire target. In the NRA Short Course, slow fire is shot in two five-shot strings, five minutes for each string, on the 25-yard slow fire target.

If you are located where you can shoot outdoors comfortably all winter, these may be the only courses you will encounter. But if you live in the cold country, your winter shooting will be indoors, where most ranges are laid out for 50-foot or 60-foot (20-yard) distances. In either case, the courses are the same—slow fire, timed fire, and rapid fire at fixed distances, with the scoring ring diameters of the slow fire target being much smaller than the rings on the target used in timed and rapid fire. The target sizes are adjusted to give about the same degree of difficulty regardless of range.

A big pistol event will usually have several matches. You’ll usually shoot a 20-shot slow fire match, a 20-shot timed fire match, a 20-shot rapid fire match, and a three-stage course, for a total of 90 shots and a possible score of 900. A big outdoor affair, often running more than one day, will have a series like this limited to the .22 handgun, another limited to centerfire arms, and a third limited to the .45 caliber guns.

In some tournaments you will run into the International slow fire and rapid fire courses, about which we’ll talk more later.

All the shooting we’ve been talking about is one-handed, with the shooter standing upright without support. People whose lives may depend on their handgun handiness want to carry things much further, and you find that many law enforcement agencies also have tough ‘combat’ courses for further training.

Secrets of success

There are many things that contribute to pistol shooting success and each helps in some measure—without them you won’t be a champ. But there are a couple of secrets that are essential to success—without them you’ll be a chump.

Eagle-eye sight is not one of the secrets. You should have passable vision. The harder test is shooting indoors, where the light is generally poor and older folks often find the front and rear sights fuzzy. Having good lighting is a big help here. A pinhole gadget fastened to your glasses or hanging down in front of your shooting eye will make sights and bull look sharper. Another solution—and the one I use—is to have a pair of glasses ground so that your shooting eye focuses sharply on the sights. Sure the bull is going to be a fuzzy mass—that won’t hurt scores.

Being strong may be some help on the range, especially when it comes to carrying ammunition cases around, etc., but it isn’t one of the secrets.

Having a calm, easy-going disposition is a help because you won’t let things rattle you when you run into trouble—or when you begin to pile up a good score. But here are the two real secrets that you must remember!

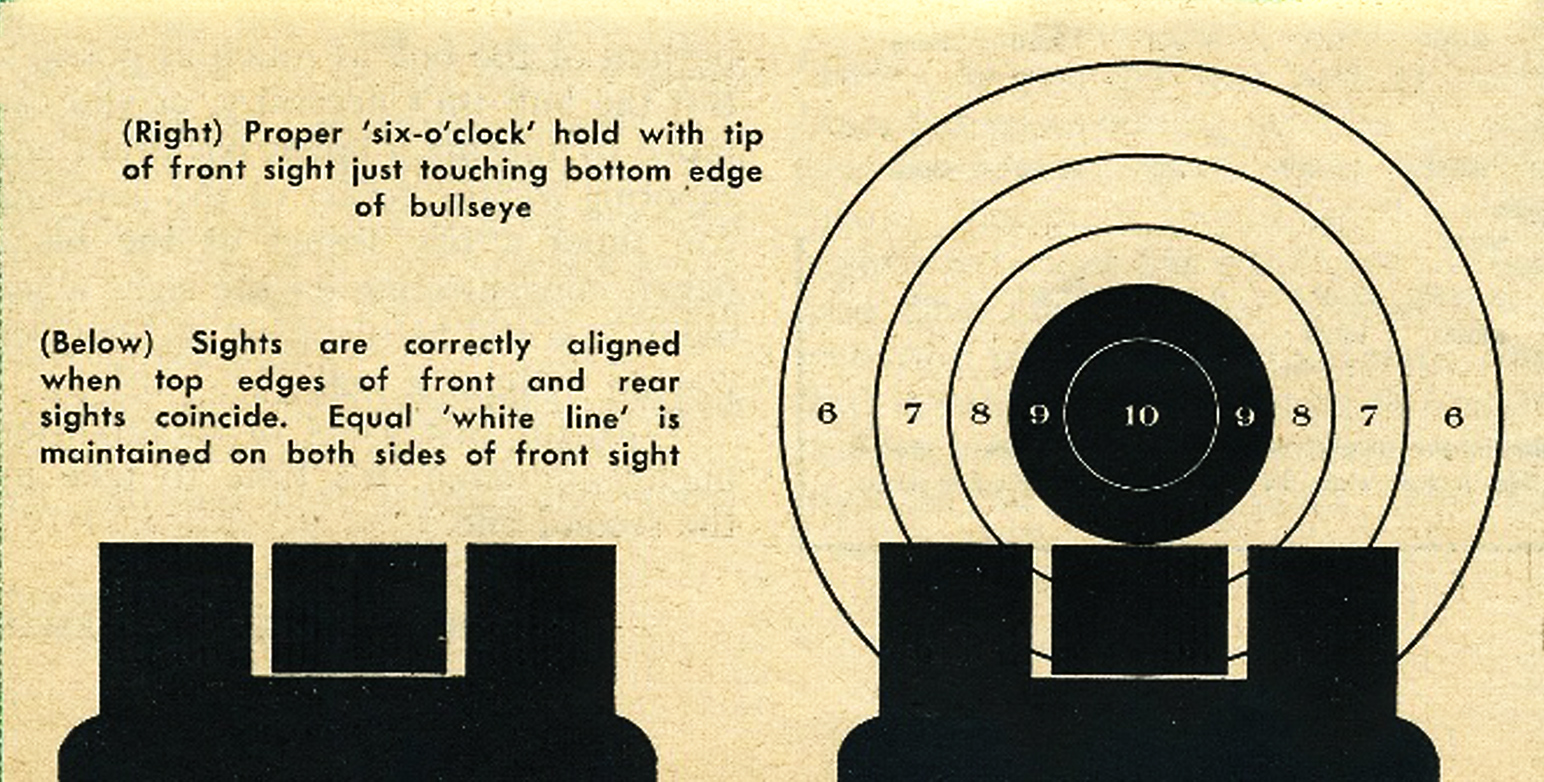

Sight alignment. Sight alignment merely means the line-up of the front and rear sights—and let’s not worry much about the bullseye yet. If you hold the pistol at arm’s length, you will find that the front sight waves around wildly, the rear sight waves around differently, and neither has any apparent intention of sticking in the vicinity of the bull. You can simplify the problem by concentrating on holding the ideal sight alignment—front sight exactly centered in the front sight notch, and the top of the rear sight. Watch it carefully—and watch it carefully all the time. As soon as you start worrying about something else, the front sight will wander away from the rear, and you will get a wild shot. Because of the short distance between sights—six to 10 inches—any sight movement here means a big bullet movement on the target.

Your intense concentration should be keeping the two sights lined up. As a secondary matter, you want to have those sights snuggled up against the bottom of the bull as much as possible. But the bull isn’t necessary, as you can prove by turning a target backward and shooting for the center of the paper. If you shoot a few strings at the blank paper, concentrating on the sight alignment, you will be surprised at how well you do without a bull.

With the first secret of success thoroughly mastered, it’s time to take up the second one.

Trigger squeeze. Perhaps ‘trigger squeeze’ isn’t the right term; maybe ‘trigger control’, ‘trigger pulling’, or some other term is better. But no matter what you call it, you want to apply pressure to the trigger so that when the hammer is released you don’t move the gun. The beginner—and many an old hand—tends to yank the trigger and he yanks the gun way off the aiming point at the same time. Because the pistol is held at arm’s length by only one hand—and none too steady at that—it is easy to flip the muzzle in one direction or another by a twitch of the hand. And a little flip of the muzzle means a very wide shot on the target or perhaps off it altogether. It take a great deal of training and self-control to apply pressure to only the trigger finger, especially when you are shooting a big gun that gives much noise and recoil. When you’ve concentrated hard, got the sights nicely lined up and sitting just right under the bull, your mind tells you to yank that trigger right now, because you aren’t going to hold that ‘just-right’ picture very long. So you grab the trigger and a shot hole shows up way out in the white. The tendency is bad enough in slow fire, but when you get to rapid fire, with its 10-second limit, it seems as though the only thing you can do is yank ‘em off as the bull goes by. But yanking is sure death to good rapid fire scores as well as to good slow fire scores. You must release the hammer without moving the gun.

Pistol shooting is very largely a matter of self-control and until you master the art, you may have trouble understanding what you are doing. Keep watching the sight alignment like a hawk before, during, and after the shot. You can often pick up a flinch if you watch carefully—and are honest with yourself.

For those who have never seen it in action, flinching is that involuntary ‘pushing down and forward’ action of the gun hand (with gun in it) just as the piece is fired. It must be overcome if the shooter wants to stay in the running. Evidently it is some sort of semi-reflex action designed to compensate for the kick and noise before they happen. It doesn’t do anything but ruin scores. Some shooters believe that the noise is as much to blame for flinching as the recoil, and accordingly recommend good ear plugs. A good way of making yourself be honest is to have a partner hand you the gun for each shot—sometimes empty, sometimes loaded, and watch for gun movement on the empty. By yourself, you should always call the exact location where each shot should hit, after you fire it but before you should look in the scope for the hole in the target. If the shot is very far away from where you called it, you can suspect a flinch.

Holding the gun. Shooting is a rough and expensive way to learn how to shoot, and you can develop some poor habits in the process. Some parts you’ll have to learn by shooting, but you can learn much without firing a shot. Working at home a few minutes a day will do a lot more good than a whole afternoon of blasting at the countryside.

One of the first things you will want to do is to toughen up your arm and shoulder muscles, so you can hold a two- or three-pound weight at arm’s length for half a minute without wobbling all over the place. You can practice this without a gun—any weight will do—and the steadier you become the better shooter you will be. A few minutes work each day for a few weeks that will give you remarkably better control of that arm.

It is more fun to practice with a gun in hand, but when you do, work hard at developing good habits. Start by concentrating on sight alignment by itself. As you get this well in hand, then put up an aiming mark on the wall and practice lining up the sights with the mark. The mark should be about the right size to look like a bullseye. When you have aiming under control, some extensive trigger work is indicated. And this is one reason for waiting so long in this training period before taking up the squeeze—so that the other items are second nature to you and you can concentrate on trigger control.

If you are working with a revolver, practice the technique of cocking it while you work on the trigger control. With your gun-hand thumb, reach over to the hammer spur and pull the hammer straight back until it’s cocked. Keep the gun pointed at the target, don’t let swing off to one side, don’t let the muzzle drop, and keep the sights in view. You want as little gun movement as possible to save time and effort and you don’t want to lose track of the sights, because finding them will cost more time. Cocking the revolver doesn’t contribute to making 10s, so you want to learn how to handle the hammer without having to think about it. Poor hammer manipulation can cause you lost points by taking too much time, by making you lose the sights, or by shifting your grip.

When you start shooting, concentrate on the basics while you learn a bit about slow fire. There’s no point in worrying about timed and rapid fire until you can shoot passable groups slow fire. As you get the feel of slow fire, try shooting a couple of shots without taking your arm down. Gradually reduce the time between shots and increase the number of shots—but don’t get careless on the basics. If you find the sight picture is getting sloppy or that you are starting to yank, slow down and start again.

Soon you will reach the stage of being able to shoot five in 20 seconds and it might pay to stop here a while and work hard on this until you get the feel thoroughly. Then go back to the speed-up, trying to whittle that 20 seconds down to 10, bit by bit. Once you get to the 10-second limit, it will pay to devote careful attention to rapid fire. Unless you’re mighty careful, the short time limit may occasionally panic you into forgetting fundamentals and turning loose five wild shots. At this stage, it’s better to shoot only four shots if they are good than to squib off five in the general direction of the target.

Nor do you get any extra credit for finishing ahead of time, so you should drill yourself extensively and know just how you are getting along in those 10 seconds. Practice getting the first shot away just as soon as the targets face you. If the first shot pops as they swing, you have about 2 1/2 seconds apiece for the other four shots and that should be enough time. But if you waste a few seconds on the first, you are shorting yourself on all the others. With someone to call commands for you, or by timing yourself, a lot of bedroom dry firing will pay off in learning instinctive hammer operation and timing, leaving you free to work on the sights and trigger.

Shooting position. Down on the firing line you will see all sorts of shooting positions. At one extreme is the man who faces at right angles to the target, sticks his arm out to the side, and then turns his head so he can see the sights. At the other extreme is the man who plants his feet firmly as he faces downrange. He holds his arm directly up in front—even a bit over to the left so he can sight. I think you will find that a position somewhere between is a better compromise. Feet should be separated a comfortable distance, without going to extremes, and the left hand should be stuck in the pants pocket or hooked in the belt.

How are you going to hang on to the pistol? That will vary, depending on the size and strength of your hand, length of fingers, type of handle on the gun, and other matters. Caliber and type of gun make a big difference. The .22 single-shot free pistol with its set trigger, the .38 revolver in timed or rapid fire, and the .45 auto in rapid fire, each requires something a little different. In shooting the free pistol with its few-ounce trigger pull, you will hold very lightly. In fact, some of the grips on the imported beauties don’t need any tight hold at all; you wear ’em like a glove. The revolver, on the other hand, needs a good firm grip with the third, fourth, and fifth fingers to keep it from slipping in your hand during recoil and during the acrobatics of getting your thumb on the hammer and the hammer back. The .45 auto calls for a mighty solid hand-hold. The hard grip will keep the gun from slipping in your hand, and will help you recover from recoil quickly during rapid fire.

Timed and rapid fire. The commands for timed and rapid fire are the same as for slow fire: “With five rounds load. Ready on the right? Ready on the left? Ready on the firing line?” In a few seconds the targets will face toward the shooter, or the command “Commence firing” will be given.

Safety, and tough range officers, demand that you do not load your gun until the command is given. In fact, your gun must be kept with magazine out, slide back, or cylinder swung out. It’s all right to load your magazines early in the game, so long as you don’t put them in the gun. “With five rounds load” is your signal to complete the loading—slip in the magazine or put the five rounds into the cylinder and close it; let the slide down or cock the revolver; be sure the safety is off; get your correct grip. Check your target number!

At the command “Ready on the right?” you can begin aiming. It depends on what stage you are shooting, how fast the range officer gives commands, and other factors as to just when you start aiming, but it’s legal any time after the command. Incidentally this is really a question, not a command, and if you are not ready that’s the time to sing out in a loud voice. When you are all squared away, the range officer will start the commands again.

The “Ready on the firing line” is the last word before the commence firing signal lets all concerned know that the range is ready to roll.

After you have finished shooting, stand quietly until the cease firing signal is given. Then remove the magazine, latch the slide back, and check the chamber, or swing out the cylinder and empty it. Put your gun down and wait for the next command.

International slow fire. If you’re an impatient character you’d better steer clear of International slow fire shooting. Not counting time for scoring and target changes, it can take up to 3 ¼ hours to fire one 60-shot match. Nor is it any better on the spectator, because the shooter disappears into a three-sided windbreak on most U.S. ranges and is gone for hours.

However, this is the way the International Shooting Union (ISU) wants to conduct its World Championships and we shoot either ISU rules or not at all. This International game is very popular in many foreign countries, whereas the U.S. game has a more limited appeal.

The International slow fire match is fired at 50 meters (54.7 yards) on the 50-meter International target. A full course consists of 60 shots, fired in six strings of 10 shots each, with a 20 minute time limit per string. In addition, a 20 minute sighting period is allowed to begin with, and a five minute string before each 10 record shots. In addition, there is a 30 minute break in the middle of things.

Generally, the slow fire free pistol is a .22 single shot with a set trigger, a long sight radius, and special grips. This sort of pistol is not very popular in the U.S., because it is limited to this one kind of not-too-popular course, and is not made here. Consequently, except for the hotshot who gets serious about this game, most of us shoot it with whatever good .22 handgun we happen to be using for the U.S. game. On such a basis, it isn’t much different from our usual slow fire matches, except for the tough target and the longer course, and if you are a good slow fire shot you should do all right. But when you start working with the free pistol and its set trigger, then you are in a different game that takes some special work of its own.

Regardless of the gun you use, when you switch over to the International target you’ll be downright discouraged. It has 10 rings in the same diameter as the five rings of the U.S. 50-yard target, and you are nearly 15 feet farther away.

International rapid fire. The International rapid fire match is shot on five all-black targets, roughly the size and shape of a man, with scoring rings marked off inside the silhouette. The five targets are placed 2 ½ feet apart, center to center, and rigged so they can be edged or faced towards you. You load up your .22 pistol with five shots, get all set, drop your arm down to a 45-degree angle, and call “Ready.” In a few seconds the five targets swing from the edged position to face you, and later on are automatically edged again. When they are faced, you raise your pistol and fire one shot at each of the targets.

You get eight seconds for the five shots. The next five shots are also given eight seconds. In the next two strings the time limit is dropped to six seconds. The last two strings have to be fired in four seconds each. If you consider this carefully, you will find that it amounts to less than one second per shot, which must include raising the gun on the first shot, and moving from target to target on the others. The first few times you try it, you either end with a couple of shots left or you blast five in the general direction of the targets. As you calm down, though, you will find that the four seconds is plenty of time to sight carefully and squeeze each shot—and, in fact, you must do these things right or you will have poor scores. Since the match is scored first by the number of hits, and then by numerical score, it pays to concentrate primarily on making hits, and then on making 10s in the eight second stages and to shoot for hits in the four second runs.

That big silhouette looks almost impossible to miss at 25 meters (27 yards) and it comes as a considerable shock the first time you find two or three blank targets. You will swear that the bullets didn’t come out of the gun, or that they disappeared into thin air—but you know you couldn’t have missed! Here you see the effect of proper trigger squeeze—or lack of it. If you rush yourself and yank the trigger, you will likely earn a miss. This isn’t to say that you can loiter in getting those shots away, because the four second limit gives no loafing time.

Since the target is all black, and since the sights are also black, it is possible to lose track of the sights on occasion, particularly if you let your gaze wander between shots. You can lick this in two ways—by painting the front and rear sights different colors or by concentrating on keeping the sights in view and in alignment all the time.

The man who rolls up his sleeves, spits on his hands, and decides to take this game seriously will probably end up with one of the special guns made for this game. It will be chambered for the .22 short and will have a muzzle brake and heavy weights up front for keeping the muzzle from flipping up and for steadying the gun. But if you have a garden-variety .22 automatic (autoloading) pistol, you can still shoot respectable scores if you concentrate on sight alignment and fast trigger squeeze.