There are few inventions predating paved roads and indoor plumbing that remain staggeringly popular today, but among those few we can name the .22 Long Rifle cartridge. Though its design is so outdated that it should have gone out with buttonhooks and buggy whips, more than two billion cartridges are still manufactured every year. With Winchester’s introduction of the .21 Sharp, the .22 LR finally gets an update.

Other details aside for the moment, what we’re looking at in the .21 Sharp is essentially a .22 Long Rifle cartridge that dispenses with the outdated 19th century technology of a heel base lead bullet and round nose. A heel base bullet is one that has a reduced diameter at the back end so that it will fit down inside the cartridge case, while the forward bullet diameter is larger to properly fit the bore’s land and groove diameters. Such configuration means the bullet diameter and case diameter are essentially the same. It also means the lead bullet’s lubricant is exposed on the outside of the bullet. The heel base is not conducive to best accuracy, the technology is long obsolete, and the .22 Long Rifle is the only popular cartridge today that still features a heel base bullet.

Within a few short years of the .22 Long Rifle hitting markets in 1887, the advent of smokeless powders and high velocity prompted development of the “metal patch” bullet to replace paper patched lead bullets. Today we call the metal patch a “jacket.” Both paper and metal coverings reduce or eliminate leading, the deposit of lead in the bore from bullets launched at higher velocities. During that same period, outside lubricated heel base bullets fell out of favor, partly because inside lubricated bullets, with their lubricant protected inside the cartridge case, don’t pick up debris and don’t leave greasy lubricant on hands and whatever else may touch the bullet. NRA Smallbore competitive shooters know exactly what that means, as nearly all .22 Long Rifle cartridges used in competition have an oily or waxy lubricant on the outside of the bullet. Jacketed bullets need no lube.

Heels or Jackets

But there was and is no economical way to jacket a heel base bullet. At least, not economical in the sense that the low retail price of ordinary lead bullet .22 Long Rifle ammo is at the very heart of the .22 Long Rifle’s long and continued success despite its doddering pre-Victorian age heel base design. Yes, there are many modern .22 Long Rifle offerings with the lead bullet “copper clad,” “copper plated” or by any other descriptor covered with an alloy of some other metal, but these are not true jackets—rather, the metal covering is extremely thin, typically applied by electroplating, the thickness of which may be measured in microns. Two of Winchester’s four .21 Sharp offerings feature true jackets; Winchester’s Copper Matrix bullet differs in being completely lead-free, and the Black Copper Plated bullet is obviously electroplated.

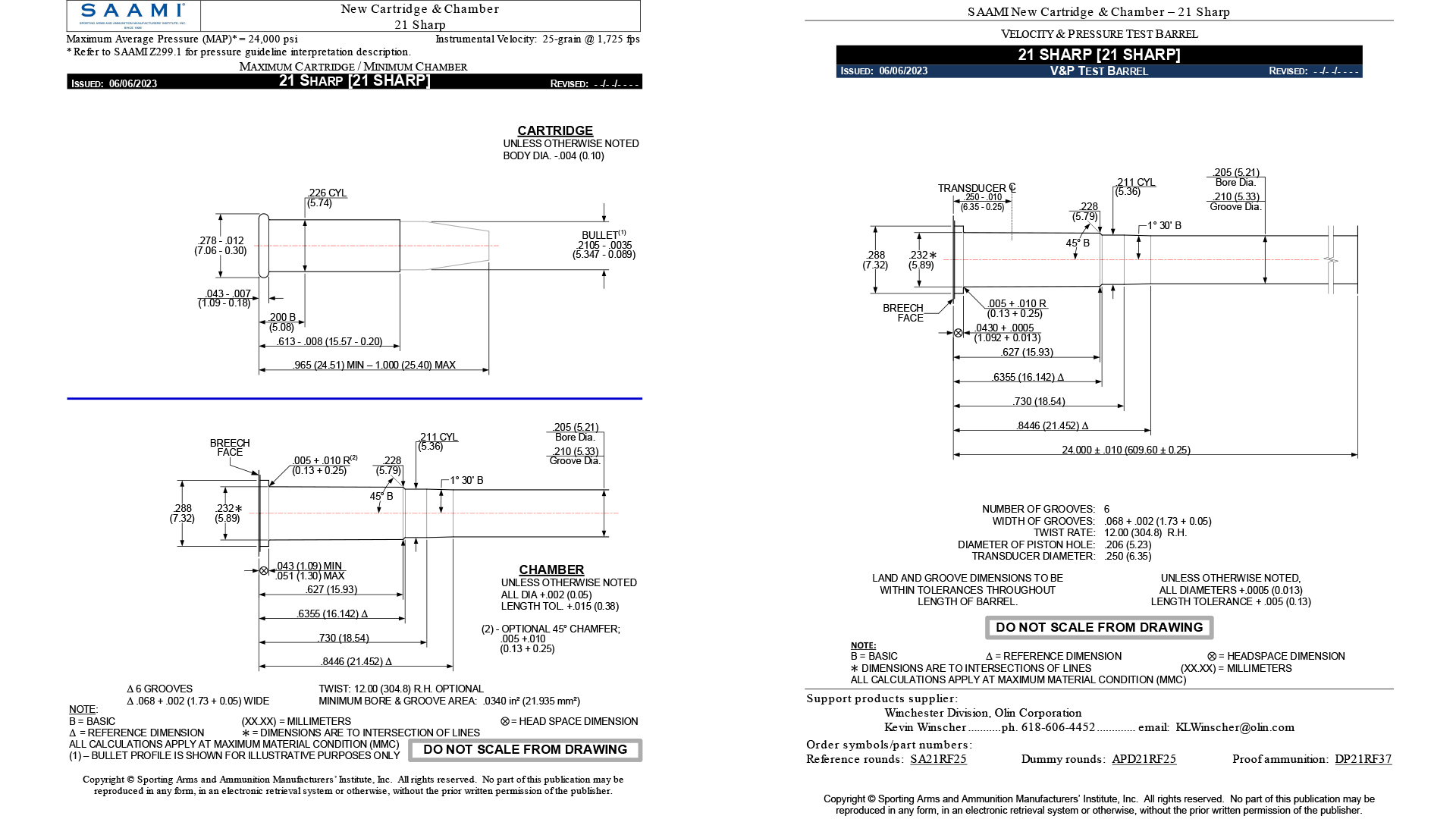

What Winchester has done with the .21 Sharp is to slightly reduce the .22 Long Rifle’s bullet diameter from .2255 inch to .2105 inch to dispense with the heel and permit use of jacketed bullets on the .22 Long Rifle rimfire case. But that slight change necessitates changing bore diameter, creating an entirely new cartridge in the manner of necking up or down an existing centerfire cartridge to make a wildcat. In leaving the .22 Long Rifle case unchanged, however, manufacturers and gunsmiths can barrel or re-barrel existing .22 Long Rifle firearms or receivers to .21 Sharp. Existing .22 Long Rifle magazines will feed the .21 Sharp. Because chamber pressure (24,000 p.s.i.), case dimension and overall length is unchanged, existing/re-barreled .22 Long Rifle semi-automatic actions should cycle the .21 Sharp without a hitch.

BCs and Velocities

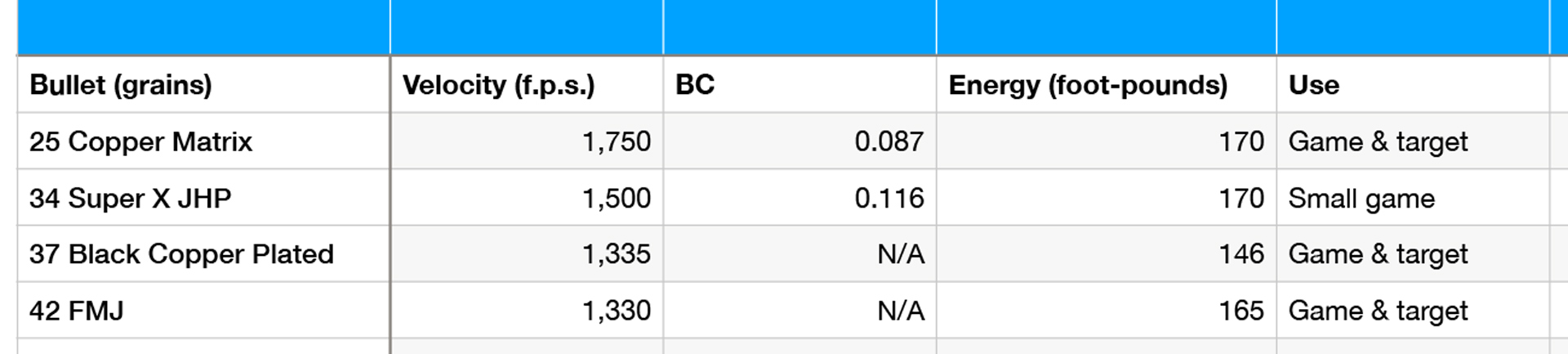

With its introduction, Winchester offers four different .21 Sharp loadings in bullet weights of 25, 34, 37 and 42 grains. Three of these Winchester lists as “Game and Target” offerings, with the fourth, featuring a 34-grain JHP bullet, intended for small game.

Among its .21 Sharp cartridges, Winchester assigns a ballistic coefficient (BC) of .116 to its 34-grain JHP bullet, and .087 to the 25-grain Copper Matrix bullet. As comparison, depending on the information source—manufacturer, ballistic app or actual shooting—the BCs of match-grade, 40-grain lead .22 Long Rifle bullets runs from about .112 to .172.

Bullet velocities of three of Winchester’s .21 Sharp loads run 1,330 f.p.s., 1,335 f.p.s. and 1,500 f.p.s., with the 25-grain Copper Matrix bullet stepping out at 1,750 f.p.s. The first three loads are in the high velocity realm of .22 Long Rifle offerings—standard velocity .22 Long Rifle is in the 1,100 f.p.s. neighborhood—while the Copper Matrix load is in fast company with CCI’s somewhat different .22 Long Rifle Stinger ammunition.

In a universe of far better choices, sometimes one may be limited to employing the .22 Long Rifle or other rimfire cartridge for self-defense. The .21 Sharp’s 34-grain JHP at 1,500 f.p.s. and with 170 foot-pounds of muzzle energy is a candidate, though Winchester doesn’t promote it for a self-defense role. Winchester literature does not mention terminal performance of the Copper Matrix bullet. At this stage, then, the .21 Sharp is intended as a plinker and small game dispatcher.

Winchester .21 Sharp Factory Loads

Winchester markets .21 Sharp only in 100-count boxes, starting at $15 per box and increasing to $25 per box. At 15 cents per round, that’s in the same ballpark as some better .22 Long Rifle, though bargain basement plinking .22 Long Rifle retails for about 10 to 12 cents per round at this writing (in 50-count boxes).

Competition?

One can’t help examining the more aerodynamic shape of the .21 Sharp’s bullets and wonder, “How about for competition?” Consider that bullet velocity is one component of the ballistic coefficient equation—this is why a bullet’s BC mathematically changes with distance (for simplicity, published BCs are typically computed with velocity at the muzzle). Compared to a .22 Long Rifle bullet’s blunt, round nose, a more aerodynamic shape can theoretically help a .21 Sharp bullet retain velocity over greater distance, imparting a higher BC at greater distance.

Match-grade .22 Long Rifle ammunition for competition typically launches bullets right at the ragged edge of (sea level) supersonic velocity, just under 1,100 f.p.s. Indeed, here in Arizona’s Central Highlands where I routinely shoot at elevations at about 5,000 feet, the thinner air sometimes allows such bullets to start supersonic. This can be a bad thing, because as supersonic bullets slow below supersonic speed, they depart stable flight and can seriously lose accuracy.

That said, so long as a supersonic bullet stays supersonic all the way to its target, that transonic barrier isn’t an issue, the same as in High Power Rifle shooting, and the reason why, for example, SK High Velocity Match .22 Long Rifle ammo, at 1,263 f.p.s., shoots fine out to about 100 meters but loses its edge beyond that. At traditional Smallbore distance of 100 yards or meters, the .21 Sharp’s high velocity itself isn’t a detriment to accuracy, but nor does its more aerodynamic bullets have a BC advantage. That advantage would begin further downrange as the round nose .22 Long Rifle bullet rapidly loses velocity while the .21 Sharp bullet retains it longer.

At present, Winchester’s .21 Sharp ammunition offerings are all far too speedy for competition at longer ranges that might take advantage of its bullets’ potentially higher BCs. Winchester’s only claim to precision for the .21 Sharp thus far is “sub-1.5 MOA groups at 50 yards” for the Copper Matrix ammunition. That’s quite good for small game and varmint hunting accuracy out to that distance, but it isn’t match ammo. As well, the Copper Matrix 25-grain bullet is far too light for precision shooting at any outdoor rifle competition distances.

Perhaps Winchester will eventually take advantage of the high-BC bullet opportunity to produce match-grade .21 Sharp competition ammunition (and rifles). Such precision ammo may not sweep away current fare at Smallbore, rimfire silhouette and other competition distance (and rules specifying .22 Long Rifle would have to be amended to permit it), but it has an obvious application in the challenge of shooting 300 yards and beyond.

Also related to competitive shooting, Winchester has said it designed the .21 Sharp to require no change in .22 Long Rifle chamber dimension, only bore dimension, and so we can expect new .21 Sharp rifles to adhere to those specifications approved by SAAMI (Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute). However, .22 Long Rifle chamber throats are designed specifically for round nose lead bullets; experiment may show that a small change in throat dimension to create a “.21 Sharp match chamber,” may coax more precision from rifle and ammunition.

Concurrent with Winchester’s release of the .21 Sharp, Savage Arms announced production of rimfire rifles barreled for the cartridge. Shooting Sports USA will evaluate rifle and cartridge when they become available.

Technologically, one would have expected the .22 Long Rifle to have dropped the heel base and occasionally donned a jacket a hundred years ago. Winchester has finally brought the .22 Long Rifle belatedly into the 20th century; let’s see if the .21 Sharp is ready for the 21st century.