While working on an article about the rapid development of concealed carry defensive pistols, I was reading the life history of James Butler Hickok, known by most as Wild Bill Hickok. I also had occasion to shoot a couple of Taylor Firearms percussion conversion guns during that same period. I noted the changes in Hickok’s guns during his life and it occurred to me that the period of his time of fame was a time of rapid development of defensive pistols as it is today.

During a relatively short period, the defensive pistol evolved from a weather sensitive, unreliable flintlock single-shot to a multiple-shot, cartridge-firing revolver—a giant leap in technology. During our time, the defensive and concealable defensive pistol has evolved from a five-shot revolver to a lightweight striker-fired pistol with a capacity of 10 to 12 shots.

According to Joseph Rosa, Hickok carried a pair of .36-caliber Colt Navy revolvers from 1861 through the time he joined Buffalo Bill’s Combination theater troupe in September 1873. In 1875 he was reported to be carrying two Colt .36-caliber revolvers converted from percussion to accept either rimfire or center-fire metallic .38-caliber cartridges until the time of his death. There are multiple legends of the guns Hickok used, but the idea of him upgrading to cartridge-loading guns from cap-and-ball guns made sense to me.

The Colt percussion revolver was considered by many to be the best possible gun during Hickok’s life. Samuel Colt was a marketing genius and inventor, but he made a serious blunder as it related to cartridge-firing pistols. An employee of Colt’s, Rollin White, came up with the idea of having the revolver cylinder bored through to accept metallic cartridges in 1852 and Colt rejected the idea. White left Colt in 1854 and acquired a patent the following year for the through bored cylinder. He sold the rights to the patent to Smith & Wesson, who controlled the patent until 1869, preventing Colt from building cartridge-firing pistols.

Samuel Colt died in 1862 at 47 years of age. When the patent expired, the company, now run by Elisha Root, had a large inventory of frames and barrels and decided to convert the existing parts into cartridge-firing pistols. The advantage of a cartridge-firing pistol over a percussion cap-and-ball gun was enormous. Cartridge-firing pistols were not only much more resistant to weather, they were also convenient to use. While reloading a modern single-action pistol is hardly fast, it’s probably more than twice as fast as loading a percussion pistol. Round count was seriously low by modern standards; the popular method of those expecting trouble was to simply carry two pistols.

The common conception is that these conversions were existing guns converted to use with cartridges; instead, they were new guns made from existing parts but otherwise converted to use cartridges. The Richards/Mason conversion deleted the loading ram and replaced it with an ejector mechanism. The cylinder was shortened at the back, and the frame fitted with a breech plate that contained a floating firing pin and a through bored cylinder that allowed firing cartridges. A loading gate was added to the breech plate and the conversion was complete. Conversions were done in .38 rimfire and center-fire, along with .44 centerfire. According to “reliable sources,” James Butler Hickok made the switch to cartridge-firing Colts by 1875 and presumably, he would have been carrying them when he was shot in the back by Jack McCall in Deadwood, South Dakota.

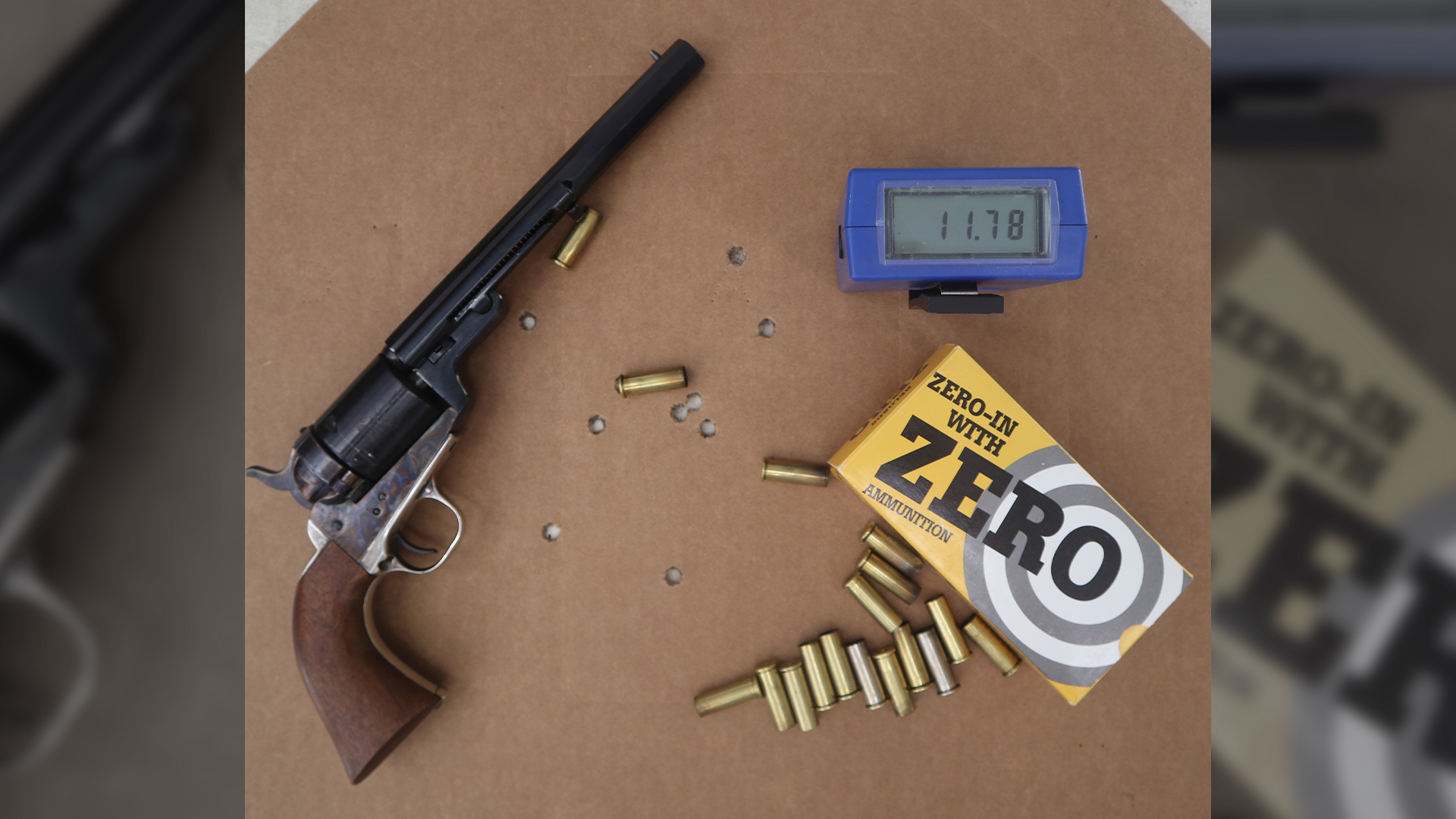

In a time when defensive handguns are the most active segment of the firearms market, a look back at the nature of a state-of-the-art defensive pistol 150 years ago is appropriate. After reading about Hickok’s life, I spotted a Traditions Mason Colt replica at a local gunshop, which haunted me for a few weeks before I decided that I needed it. It replicated an 1851 Conversion with a 7.5-inch octagon barrel and a hefty weight of 44 ounces. While this was a defensive gun, it was hardly light or easily concealable. Currently, the 1851 Navy C. Mason Revolver is imported by Taylor Firearms.

While my Colt Conversion replica is chambered for .38 Special, the gun it represents would have been chambered for .38 rimfire or .38 center-fire. Ballistics would have been similar to the modern .380. It would have been loaded with a round-nosed lead bullet, and in today’s world would be a poor stopper. Of course, it would have been a blackpowder round, meaning a thorough cleaning of the gun after each use would have certainly been a good idea.

Still, it would have been a huge improvement on the percussion guns and remember that just 25 years previous, only single-shot percussion pistols would have been available. Loading is accomplished by putting the gun on half cock, opening the loading gate and inserting a cartridge, rotating the cylinder 60 degrees and loading the next. Since a gun dropped on the hammer would likely fire, the standard practice was to load the first chamber, skip one and load the next five. This would allow lowering the hammer on an empty cylinder; the technique is today referred to as a cowboy load.

I do qualification for private security groups and decided to run the Colt through one of the standard drills I use in training. The drill is to start at five yards, with the gun holstered or placed on a table at 10 yards. There are two USPSA targets spaced six feet apart and cover at 10, seven and five yards. On the timer’s beep, the shooter runs back to cover behind the table and fires one shot at each target from right and left of the 10-yard cover. He or she then moves up to the seven-yard barrel for one shot left and right and repeats at the five-yard cover.

It was surprising to learn that there was little difference between running the drill with my daily carry SIG Sauer P365 and the Colt conversion. The sights were not great, but usable—a little time was lost thumbing the hammer because it was done during the transition from left to right side. My best times on the drill are slightly more than 10 seconds, and I only lost about a second with the Hickok replica.

The definition of the word legend is “A traditional story sometimes popularly regarded as historical but unauthenticated,” and Wild Bill Hickok was certainly a legendary gunfighter. Most respected accounts of his deeds represent him as an honorable man who used his guns in self-defense and to enforce the law. Replicas of his Colt conversion handguns are a window to the past—an era of transition to cartridge-fired guns.

Read more: 5 Things You Didn’t Know About Colt