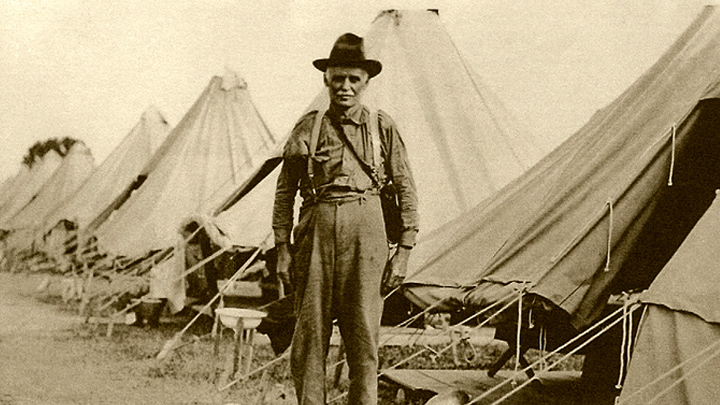

Competitors who reported to Camp Perry's firing lines on the afternoon of Sept. 9, 1921, didn't know they were about to witness a feat never before accomplished and never since equaled. But, that is precisely what was about to happen. George R. "Dad" Farr was preparing to shoot the Wimbledon Cup match for 1921.

George Farr was from Washington and a member of the state rifle team. No one seems sure what he did for a living. Some said he was a lumberjack, others said gunsmith. It may depend on when someone knew him. All who did know him agreed that he was a fine shot and a good man.

Farr apparently brought only a handmade spotting scope and stand, plus a change of clothes. In those years a shooter didn't need much of anything else. Ammunition was provided, through non-issue ammunition was permitted in NRA-sponsored matches. Shooters who did not own a rifle could, as Farr did, draw a Model 1903 Springfield from the Ordnance detachment. Upon receiving their squadding, competitors were given a schedule of where to be and when to be there. Housing was provided. Shooters ate in the Mess Hall.

During the course of the matches, the rifle Farr drew when he arrived broke down. So he turned it in to the armorers and drew a substitute rifle. That would have been routine except that he was squadded to shoot the Wimbledon Cup match on the 4 p.m. relay and he had only 600-yard dope for the sights, nor did he have much experience with the issue ammunition. Farr went to the firing line with an unfamiliar rifle and ammunition, prepared to shoot a 1,000-yard rifle match using only data provided by the manufacturers—22 minutes up from a 600-yard setting.

Farr's first sighting shot was a three. (The target had a five-point black bullseye, and three and four point scoring rings.) His second sighter was a five. He then shot 20 consecutive record fives. He only paused after the 19th shot. "I'd never shot a possible at 1,000 yards; note even a 10-shot one," he said later. "So I was a little bit shaky, but I looked around and nobody seemed to be paying any attention to me, so I fired." When his 20th shot came up a five, he got up to leave.

In those days ties were broken by shooting until you missed the five-point bullseye, so the Range Officer suggested that Farr continue to shoot—"You might win something,"—and volunteered to find some more ammunition. He spent nearly two hours finding ammunition because Farr kept shooting until he had a total of 70 fives for record. By that time it was 6:10 p.m. and the light had dropped so that Farr's 71st shot was a four.

The remarkable thing in all this is that Farr was 62 years old in 1921, not real old now, but beyond the average life expectancy for 1921. Regardless, Farr's shooting would still be a real feat. Seventy shots prone, using a high power rifle without a letup, is an ordeal for someone half his age. And, if you've never looked through the sights of an M1903 Springfield, you'll appreciate how good his eyes were.

Farr did not win the Wimbledon. A Marine named Adkins did, using a telescopically-sighted Springfield. But, Dad Farr's shooting (and the fact that were a number of long runs of bullseyes shot in the long-range matches at Camp Perry in 1921) caused the NRA and the National Board to add the tie-breaking V-ring to the Army's "C" target beginning in 1922. That's why his record remains unbroken.

Farr's performance was sufficient to prompt his teammates from Washington to buy him the rifle to take home as a memento. Another state's team bought him a case of ammunition. The shooters at Perry in 1921 put in to buy and donate the Farr Trophy, to be awarded to the high-scoring service rifle shooter in the Wimbledon Cup match. Today, service rifle shooters on the Wimbledon course fire a separate match—the Farr Trophy Rifle match—so that a service rifle shooter can no longer win both the Wimbledon and the Farr.

See more: Looking Back At Camp Perry's Mess Hall