The Civilian Marksmanship Program’s receipt in February of nearly 100,000 M1 Garands repatriated by Turkey and the Philippines brought both satisfaction and excitement to shooters and collectors of the historic and venerable rifle.

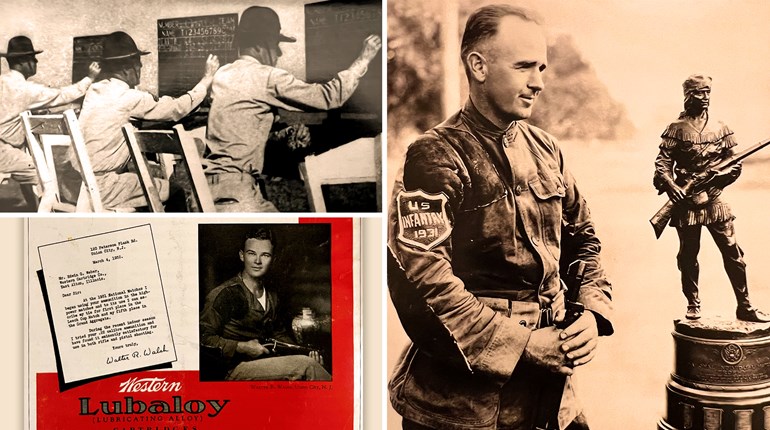

Especially for those who enjoy using it to compete in CMP’s As-issued John C. Garand matches, the M1 Garand is a piece of living history, a connection to WWII and the men who fought across islands and continents to carry the rifle in triumph into the very capitols of America’s enemies. The Garand was this country’s battle rifle in the Korean War, too, and in the hands of tough men it was instrumental in saving South Korea from communist would-be conquerors. But few recognize the M1 also served in a major way well past that conflict. Ironically, or perhaps fittingly, the respect that the Garand earned in battle later defended the freedom it had brought merely by being present where danger loomed.

These Garands that are coming home have an additional historical significance that warrants mention—their repatriation is a long overdue closure to the end of the M1 Garand’s last and longest war, the Cold War.

Doctrine of defense

At the close of WWII, the Soviet Union violated its agreement to pull troops out of Iran and instead began increasing troop presence there. Concurrently, the USSR supported Greek Communist guerillas and rattled sabers on Greece’s eastern border, and in 1946 openly attempted to obtain control of Turkey by political pressure. Not satisfied with controlling Eastern Europe, the USSR was actively bent on ceaseless expansion.

Neither Greece nor Turkey could resist the Soviet Union, so in 1947 President Truman championed the Greek-Turkish Aid Bill, establishing the U.S. policy of containing Soviet expansion with what came to be called the Truman Doctrine. Supporting his bill, Truman told Congress, “The free peoples of the world look to us for support in maintaining their freedoms. If we falter in our leadership, we may endanger the peace of the world, and we shall surely endanger the welfare of our own nation.”

The Military Assistance Agreement of 1947 and the Mutual Defense Assistance Act of 1949 quickly followed the Greek-Turkish Aid Bill, and the U.S. sent arms for Turkey’s defense, including the loan of tens of thousands of M1 Garand rifles. These Garands that helped block communist expansion on the Continent and the in Near East have been serving overseas for nearly 70 years.

Militia M1s

At about the same time, the Chinese communists defeated the Nationalists, and Soviet-backed communism quickly spilled over China’s borders. No Far Eastern country could withstand Chinese communist expansion, and the newly independent Philippines was at risk. M1 Garands had already served in the Philippines; defending against the Japanese invasion was the rifle’s very first combat duty. Some of the first issue rifles that rolled off the manufacturing line went to Filipino and American troops there in 1941 where, MacArthur said, “The Garand rifle has proved itself excellent in combat in the Philippines.”

After WWII, the Truman Doctrine provided thousands more M1s to the Philippines, where much of the threat to stability was, and still is, internal. Many of these M1s eventually disseminated from the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) to the Citizen Armed Force Geographical Units (CAFGU), a kind of active militia that serves beside regular Army forces, as the AFP later upgraded to M14s and M16s. But Filipino insurgents of the New People’s Army (NPA) acquired Garands in numbers, as well, whether via theft, graft or some other avenue. Bruce N. Canfield’s exhaustive work, The M1 Garand Rifle, includes relatively recent photos of a masked insurgent wielding an M1 and piles of Garands captured (or recaptured) by the Philippine government.

History for sale

These Garands loaned to Turkey and the Philippines remained the property of the U.S. Army, and repatriation occurred through that organization. Repatriation was desirable for all the nations involved, as keeping the now-obsolete rifles in useless storage cost money and risked loss (indeed, it is likely that many of the Filipino NPA Garands were stolen from storage). The modern U.S. Army has no use for the semi-auto Garand chambering an obsolete military cartridge limited to an eight-round magazine capacity, so the rifles went to CMP under its government charter to sell them as military surplus. Profits from the sales support the organization financially.

With all history aside, the condition of these repatriated Garands is a matter of pragmatism for those eligible citizens who will be purchasing them. Turkey, for the most part, has an environment that is more arid than the Philippines, which is both tropical and widely exposed to salt air from proximity to the ocean. It’s natural to expect that the Turkish Garands will be in much better overall condition than the Filipino M1s. However, CMP cleans and inspects every rifle before putting them in the sales racks, and assigns prices based upon the individual rifle’s condition, which CMP grades as Rack Grade (NRA Fair), Field Grade (NRA Good), Service Grade (NRA Very Good) and CMP Special (NRA Excellent). The CMP also sells “Correct” and “Collector” grade Garand rifles.

History, lost?

Unfortunately for history buffs, CMP Chief Operating Officer Mark Johnson said that neither the Turks nor the Filipinos added their own respective markings to the loaned rifles. “They are indistinguishable from any other Garand,” he said. The CMP is not separating or identifying the Turk or Philippine rifles in any way before sale.

Yet, there are two intriguing historical notes we can append to the Philippine Garands, one is clearly in error yet may have a kernel of truth in it somewhere, and the second is perhaps a billion-to-one shot—but still not entirely impossible.

First, a Wikipedia list of arms in possession by the Philippines includes 36,930 M1C and M1D Garands. These models, of course, are scoped sniper variants of the Garand, and that number is extremely unlikely, as it far exceeds the known total number of M1C/M1Ds built. However, one might imagine the possibility that some of the approximately 2,600 M1Cs loaned to the Philippines could be among the recently repatriated Garands now awaiting inspection in CMP crates and racks.

Second for consideration is the oft-misunderstood “Tanker” Garand. The roots of the Tanker are in Springfield Armory’s 1944 M1E5 experiment to shorten the Garand’s barrel and mount a folding metal buttstock for paratrooper use. Springfield Armory dropped the pursuit before the end of the year, but it resurrected a few short months later as the experimental T26 carbine-length Garand that retained the full wooden stock, only shortening the barrel to 18 inches (as well as shortening/modifying associated relevant parts). Springfield Armory quickly dropped the T26 experiment, too, so there was never a military issue Tanker Garand. Most of today’s Garand shooters know that the Tanker Garand was a clever commercial plagiarism (dating to the 1950s) of the T26, its advertising moniker playing upon the implication that the shortened Garand was small enough to fit in a battle tank. Springfield Armory, Inc., the commercial company, not the government armory, turned out some of these Tankers in the 1980s, as well.

However, lesser known is that in 1944, the U.S. Sixth Army in the Philippines modified about 150 Garands (or at least the Pacific Warfare Board apparently ordered modification of that number) by shortening the barrels. How many the Sixth Army ordnance unit actually made is unknown, and as Canfield points out, the odds of one still existing “are all but nil.” Still, in a batch of 86,000 repatriated rifles, one can dream.

Beyond the fun of speculating what diamonds may glitter amongst the gold of these repatriated rifles, those who have the perception of history can sense we are at a special moment. Great masses of humanity celebrated riotously in the streets of the world at the end of WWII, and the armistice in Korea brought tremendous national relief. Peace, however, was always a very fragile and elusive thing during the Cold War.

These repatriated rifles won’t receive the welcome of returning victors by crowds of cheering citizens; their return is even opposed by those who wear the blinders of naiveté and ignorance. But these veterans will find homes among many Americans who understand the lessons of history and who appreciate the many decades of service they rendered to us through our allies.