Competition spawned the Civilian M14

The M14 rifle was first adopted into U.S. service in 1957. The first guns reached the hands of soldiers in 1959. Depending on whose history you read, the M16 replaced it between 1962 and 1966—making the service history of the M14 very short lived indeed. In spite of its remarkably short service record, it’s considered by many to be the best combat rifle the U.S. Military ever used. While the service record of the M14 was short, it ruled the ranges in High Power Service Rifle competition from the mid-1960s to the mid-1990s. In 1966, the first year the NRA and National Board for the Promotion of Rifle Practice used the new 10X target, the M1A won its first National Trophy Individual Match (NTI) at Camp Perry. Sgt. Robert Gollem fired a 471-11X in the first of many NTI wins for the M14. The highest score in the NTI with an M14 was Greg Strom’s 495-22X in 1984. The current high score with the current M16 design is a 497-22X, fired by Marine Staff Sergeant Jason Benedict in 2007.

It was only natural for civilian competitors to envy the M14, and from the popularity of Service Rifle competition came the impetus to create a civilian version of the M14. While all civilian versions of the M14 rifle are commonly called M1As, the only real M1As are receivers and guns built by Springfield Armory, who owns the copyright for that designation. There are conflicts in the story of just who built the very first civilian versions of the M14, but there are no arguments about who the original players were; Elmer Balance and Melvin Smith came up with an early version in Devine, TX, at about the same time as Carl Maunz was working on his version from El Monte, CA. As a result, both early versions were developed at about the same time.

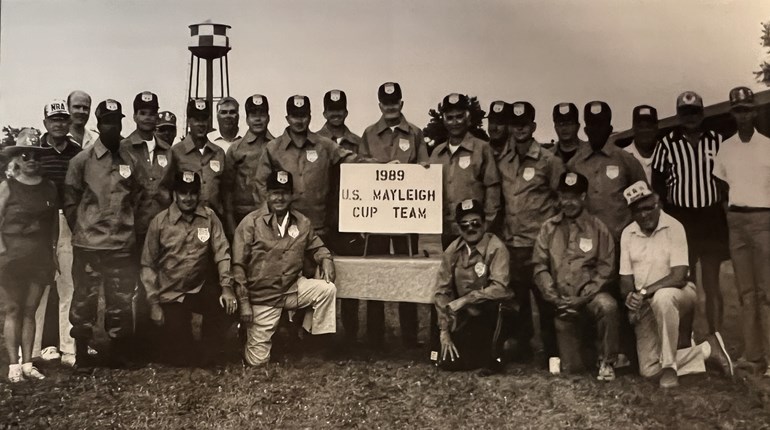

While the M1A has gained popularity as a multipurpose recreational rifle, it was competition that fueled its conception. Everyone involved with the early development of a civilian version of the M14 was involved in Service Rifle Competition. From the time of its first availability until the rise of the M16/AR15 as a match rifle in the early 1990s, the M14, M1A and other civilian versions completely dominated service rifle competition. When Bob Reese acquired the M1A in 1974 and formed Springfield Armory in Geneseo, IL, he recognized there was a market for civilian versions of the basic M14 rifle, and the company has been supplying receivers and building M1As for competition, recreation and hunting use ever since.

My experience with the M14/M1A has been a long and pleasant love affair. After beginning my High Power career with an M1, shooting just enough to qualify for a DCM M1 for $121.50 in 1983, I drew an M14 from the North Carolina State Team and entered the North Carolina State Championship. At that first match, early in 1984, I won the Marksman class with an Expert score and fell in love with the M14. Eventually, I got my Distinguished Rifleman badge and earned four Dogs of War medals for the National Trophy Team Matches with M14s and M1As. I began with a standard weight National Match M14 and finished up with an Alan Hurt-built M1A with a Hart barrel. I continued to shoot the M1A for years after getting distinguished and never felt under gunned.

The accuracy potential of the M14/M1A is unquestionable. During their reign as service rifles, they produced multiple perfect 200 scores at 600 and 1000 yards in the hands of top shooters. This is a difficult feat with a modern scoped magnum caliber rifle and remarkable with an iron sighted battle rifle. Good competition rifles can group 10 shots under one MOA, and the meticulously massaged rifles used by the top shooters during my career would consistently put up 10 shots under an inch at 200 yards off a test cradle.

It seems a look back at these rifles and their capabilities is reasonable, since our military is currently bringing the M14 out of mothballs and creating the Enhanced Battle Rifle (EBR). The EBR is a standard M14 with a shorter barrel installed into a folding chassis stock with rails for accessories and sights.

Four Decades of M1As

The AR Sales rifle represents the very beginning of the M14 clones. It’s one of 225 of the very first M14 clones built into a state of the art rifle for its day by one of the pioneers of the M14 clones, Karl Maunz. In 2013, I had the pleasure of sharing a target at Camp Perry with Mr. Maunz, then 75 years old and still shooting strong. His story was that he was on the Army Reserve team and designed the clone receiver because the Army Reserve had no access to M14 National Match rifles, so he got involved in providing a civilian version. These were custom order rifles and serial numbers—even brand names varied widely. Some guns were labeled Maunz Match Rifle, some H&R, and some, as my gun, AR Sales. There’s a lot of controversy about who actually made the first M14 clones and the stories vary.

The Maunz rifle used an air gauged, Douglas barrel, has a unified gas system, a different recoil spring guide, and a standard National Match stock, glass bedded with a walnut insert to fill the cut for the full auto switch. The glass bedded M14 National Match stock is much slimmer and lighter compared to later competition rifles. While the later guns used a pinned operating rod guide, the early versions had the operating rod guide welded on, or dovetailed into the bottom of the barrel and silver soldered into place. This was required because the standard operating rod guide wouldn’t fit the heavy match barrels. With a serial number of 0104, my AR Sales rifle would have been from the very earliest days of M14 clones, probably around 1975. The Maunz rifle would have sold for around $1,200 in the mid-seventies. Only 225 were built in total.

To represent the heyday era of the M1A on the rifle range, I chose an Iron Brigade Armory, state of the art rifle from the early 1990s. During that time, many competition rifles were built from the ground up on Springfield Armory receivers.

The Iron Brigade rifle features all the above features, along with a pinned operating rod guide on the barrel and two lugs welded to the receiver to allow bolting it into the stock, for an even more secure mating of the receiver to the stock. The M1 and M14 rifles use a unique system of securing the action in the stock, consisting of hooks that are part of the trigger guard which cams into matching cuts in the receiver ears. During the later years of the M14’s domination of High Power competition, some rifle builders added to this system by modifying the guns with lugs and guard screws. The idea was to make the glass bedding last longer, but many successful teams' rifles never incorporated the modification. Most found that good glass bedding lasted as long as the barrel, and the bedding was easily freshened up when the rifle was rebarreled. In the early 1990s a top-of-the-line, double lugged rifle like the Iron Brigade Armory sold for around $4,000 with all the bells and whistles.

To represent the current M1As, I chose a Super Match Springfield Armory with the heavy, premium, chrome moly barrel and oversized wood stock. It comes with all the modifications that allowed the remarkable accuracy of those early match rifles, like a unitized gas system, a modified recoil spring guide, a better trigger, glass bedding and National Match sights. The Springfield Armory Super Match incorporates the rear receiver lug for more bedding surface, though there are no screws to augment the trigger hook system, probably because time proved the trigger hook system is sufficient. Available upgrades for the Super Match include stainless barrels and McMillian fiberglass stocks. The Chrome moly barreled, wood stocked, Super Match currently sells for $2,799.

While genuine M14 rifles were unavailable to civilians, so was the M118 ammunition used by the military. Civilians only got a chance to shoot M118 ammunition through the then DCM’s National Board for the Promotion of Marksmanship matches. The standard load for civilians to replicate M118 was a Lake City Match case with 41.5 grains of IMR 4895 with a 168-grain Sierra MatchKing. Since the MatchKing was considered superior to the 173-grain Lake City bullet, many military teams chose to pull the 173s and replace them with 168 MatchKings. While I have no information on why, these loads were referred to as “Mexican Match”.

Later, the Army developed a dedicated match load, designated as M852, using the same case, primer and powder with the Sierra bullet. This load was superior to the M118 and in my experience on the test cradle, was even superior to the most carefully crafted handloads. When I was running the North Carolina team, we tested the club’s M14s and M1As annually. Never once did a reload outperform M852. I’ve always suspected it had something to do with the primer Lake City was using. Depending on who was running Lake City, M852 was loaded with either IMR 4895 or Winchester 748.

All these rifles represent a different era of the M14 clone legacy. While they’re different, they share many of the same features that allowed the M14 and its clones to dominate Service Rifle competition for so many years. As racing improves automobiles, competition improves firearms, and the current crop of Springfield M1As, from the Basic to the top of the line, Super Match and Loaded models, reflects the years of development. The M14 and its variants are still in service today and it’s still considered by many to be the best battle rifle in the history of the U.S. Military.