If we could guarantee winning High Power matches by simply reading an article or hanging a widget on our rifle, there’d be more National Champions than Marksmen. You, as well as I know that the number one thing we can do to move toward success is to practice. But an article that merely repeats the word “practice” five times isn’t very helpful and besides, the key word here is “quickly,” so what’s available to us that might improve our scores that doesn’t entail endless dry firing and cerebral focus on wind flags? Let’s brainstorm a bit.

1) Get a coach

I was very fortunate to begin High Power competition by invitation to join a Navy team, and the team was very fortunate to have Harry, a retired gentleman competitor, as coach. I also received some coaching from the team captain who, wise in the ways of competition, introduced me to the concept of—ahem—“sandbagging,” but that’s a different story. Without a doubt, the assistance and encouragement of these mentors caused my skills to make an immediate leap forward.

If you’ve been winging it alone or otherwise feel you’ve plateaued, get a coach. A good resource is your local gun club; if it’s got at least a 100-yard outdoor range, it’s probably got a core of High Power enthusiasts who shoot on reduced targets. Even if they can’t hook you up with a skilled teacher, you might learn a thing or two from another High Power shooter who closely watches and critiques your technique while you focus on your shooting during a few practice sessions.

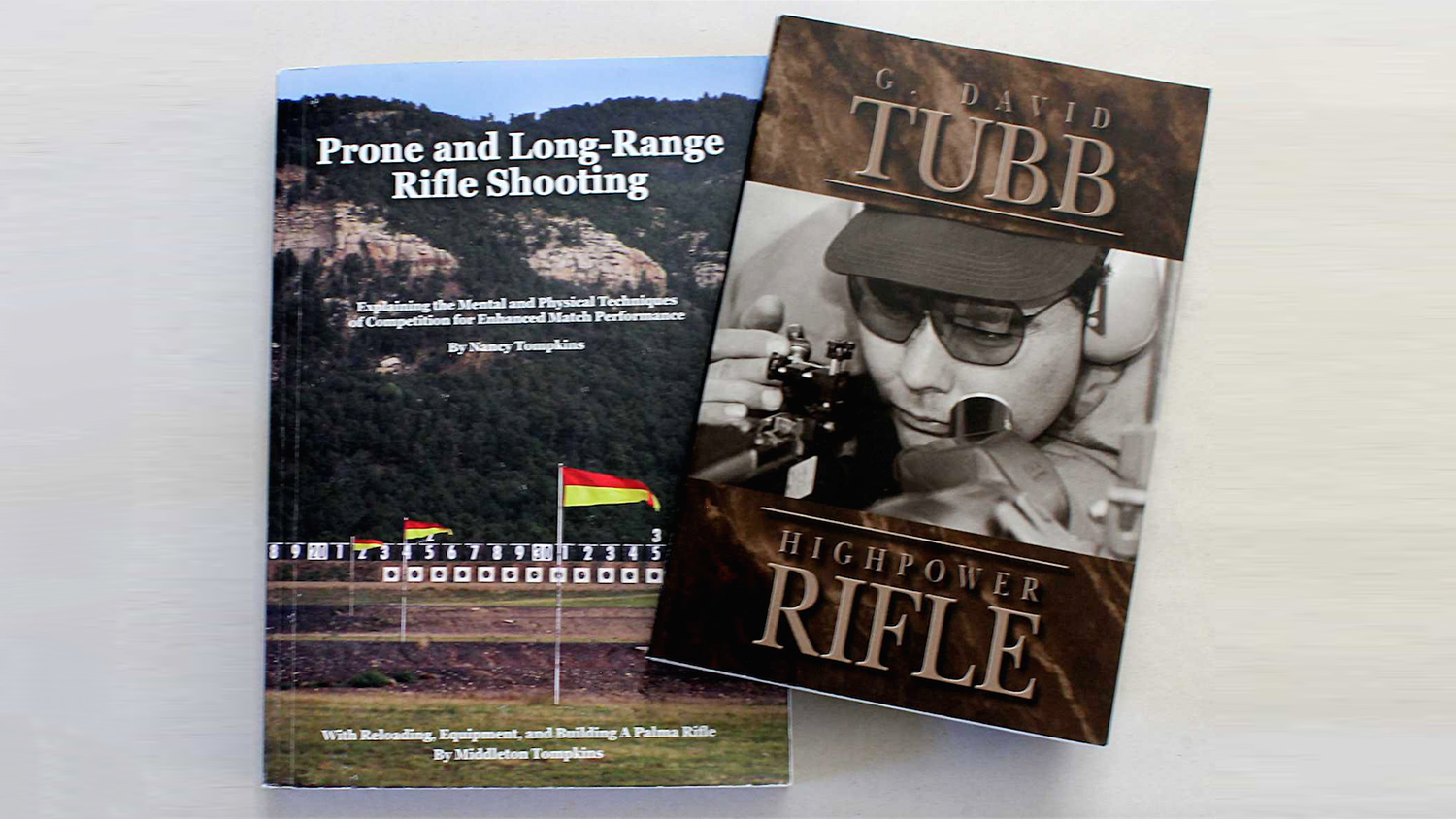

If a coach just isn’t going to happen, several top shooters have shared their own thoughts and techniques in excellent books. Two that come immediately to mind are David Tubb’s Highpower Rifle and Nancy Tompkins’ Prone and Long Range Rifle Shooting. Tubb’s book has a focus on the physical mechanics of position shooting the Match rifle, but his commentary is applicable to the Service Rifle, too. While prone shooting is only half an across-the-course match, Nancy covers it exhaustively, as well as many other aspects of competition you may not have considered. She offers a lot of positive insight into the mental approach, and her 55-page chapter on shooting in the wind can help the light come on, too.

2) Get a second job—or handload

In the U.S., we tend to behave as though we can solve any problem if we just throw enough money at it. Sometimes it works. Precision shooting is a learned skill; to shoot well we must shoot often, and that requires quantities of ammo. But beginners especially must also require quality in ammunition if they are to develop the ability to “call” their shots. Yes, match grade factory ammo costs more than “blasting ammo,” but the latter can leave the beginner confused and frustrated as he tries to understand why the offhand 12 o’clock 10 he called is at three o’clock in the 8-ring.

Cost is why a great many High Power shooters are also handloaders: we can make our own quality ammo for about the cost of cheap milsurp. It doesn’t take years or even weeks to learn how to handload; I teach a monthly basic handloading class that packs 30-plus years of experience into a single Saturday. Just as with a shooting coach, a knowledgeable handloader with teaching skills can jump start your handloading right out of the gate.

3) Lighten up

Even if the recoil of .30 caliber rifles is not a flinch factor for you, switching to the 5.56 NATO/.223 Rem. cartridge can be an eye-opener. For myself, making the switch from the M14’s 7.62 mm to the AR-15’s 5.56 mm not only brought my 200- and 300-yard scores up somewhat (it took me longer to learn to really twist that windage knob at 600 yards), the lighter recoil made shooting more pleasant.

Less recoil allows for faster recovery in rapid fire stages, which equates to a smidgen more time for confident sight alignment and trigger squeeze, which in turn is likely responsible for a few more points.

4) Ergonomics: Let’s get mechanical

This factor also ties in with number three and number five. The AR-15’s vertical pistol grip may work better for you than rifles with straighter pistol grips, as it can allow a more relaxed wrist. I also shoot the M1 Garand, Springfield and foreign bolt guns in As-issued Vintage Military Rifle games, and the difference in grips between them and the AR-15 is night and day. The AR’s elevated sights combined with that straight-back buttstock work well for many shooters in offhand, too.

If you haven’t yet tried the “no-pulse” configuration of the M1907 leather sling, you might be surprised at how well it works to eliminate the arterial pulse that moves the front sight across the target during 600-yard slow fire. Downside: Rules require the sling be mounted to the rifle (but not used for support) in offhand, this configuration won’t attach to the rear swivel, and it takes a few minutes to change the configuration. Solution: Rules do not prohibit changing slings during a match, so we can use a standard configuration sling at 200- and 300-yards and a no-pulse configured sling at 600 yards. Or simply attach a web sling to the rifle for the offhand stage.

We can make the rifle more ergonomic with the addition of a weight in the forearm that gives the muzzle more hang time on the black, or in the buttstock that provides a feeling of more muzzle control. Adding weights both fore and aft to provide a more solid feel to the “mouse gun” might work for you, too.

Try a two-stage trigger that stacks some weight on the first stage and breaks with only a pound or two on the second stage. You’ll find you have more trigger control, especially in the offhand.

As for sights, it’s been legal for some time now to utilize an optical lens inside the rear iron sight. A more recent rule now permits mounting full-on 4.5x optical sights on an AR-15 flattop rail. As time passes we may find it necessary to go to an optic just to be competitive, unless future rules separate optic and iron sight Service Rifles into their own categories.

If higher scores are your only goal, then consider moving from the Service Rifle to the Match Rifle. You may not necessarily win matches, but your scores will likely improve with the step up in inherent accuracy and the adjustability of tube guns, as well as in using the high-BC 6 mm and 6.5 mm bullets typically fired in them.

5) Let’s get physical

You’ve probably heard older shooters say, “I like High Power but I can’t get into position anymore.” Rather than give up rifle competition, they move into prone-only games like Long Range, or offhand-only Silhouette, or maybe start a new focus with Precision Pistol. At my gun club one of these flexibility challenged but stubborn guys puts on a monthly informal High Power-type match shot from the bench at NRA reduced targets.

Clearly then, across-the-course High Power shooting requires some level of fitness, even though it may appear pretty sedate to a spectator. Developing some upper body strength, especially for smaller shooters, can aid in controlling a rifle muzzle in offhand and in maintaining a steady prone position for 20 minutes of 600-yard slow fire. The gym, as much as the range, may help raise your scores.

As we get older or work in not-so-physical jobs it’s just a fact of life that we naturally lose flexibility, so we must work at staying flexible. The stretching we see athletes perform before a game also benefits us before a rifle match. The mechanics of yoga is just a formalized and logical progression in body stretching, and it works well for a great many people who have no interest in the other aspects of yoga. That said, yoga’s meditative side dovetails with modern ideas about the mental aspects of competitive shooting sports. Today, most towns in the U.S. will have yoga classes available.

Yoga and High Power—who’d a thought it? Once at a match my coach shared an anecdote about a right-handed shooter he knew who sometimes shot left-handed, “to balance his karma,” he said. My team members laughed politely, but newbie me furrowed my brow and asked, “Did he shoot better scores?”

And for goal-oriented competitors, that’s really what it comes down to.