The sale of military surplus arms has been an American tradition since at least the end of the Civil War. Sales benefitted the U.S. Government, as well as private enterprises like Bannerman’s that bought surplus arms to sell on an unrestricted American market. More recently, for 20 years now income from the sale of U.S. milsurp rifles has been instrumental in the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP) keeping citizens engaged in marksmanship training and practice, but those guns are running out.

Shooters eagerly anticipate the possible arrival of more American milsurp firearms to CMP warehouse racks, but any way you look at it, the supply, in the end, is finite. Then what? To see where we might be going, we need to take a look back at where we’ve been.

Running out

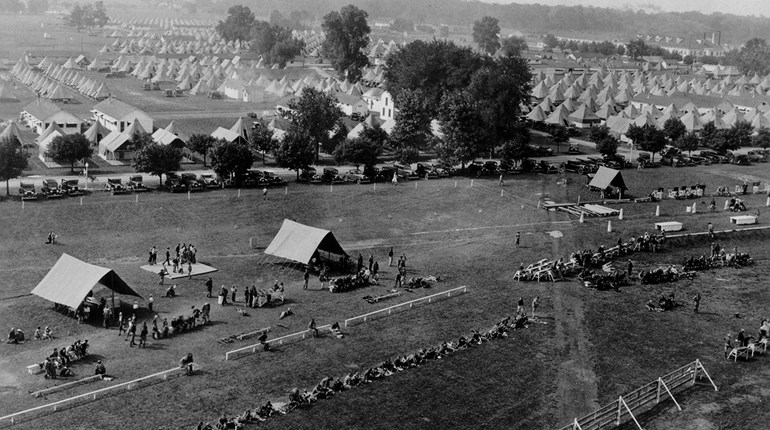

Beginning in 1907 the Army’s Director of Civilian Marksmanship (DCM) and NRA worked hand-in-glove to conduct marksmanship training and competitions for civilians. DCM sold surplus military rifles, handguns and carbines to shooters through the NRA to help defray costs and to provide affordable firearms for competition. DCM also provided no-cost ammunition for competitions. In 1996, Congress closed DCM and replaced it with the non-profit Corporation for the Promotion of Rifle Practice and Firearms Safety (aka the CMP). The Army transferred remaining stocks of surplus firearms and ammunition to CMP to sell to support itself, leaving to the future the problem of CMP’s continuous income.

Now it’s the future. The U.S. surplus ammo ran out long ago, CMP’s stock of M1 Carbines, M1917 rifles, .22 cal. rifles and Springfields is gone, and the supply of M1 rifles nearly so. According to CMP Chief Operating Officer Mark Johnson, the last of the milsurp M1 Garands may be gone before 2019, so income from surplus rifle sales is nearing an end. Enter the surplus M1911A1 and (maybe someday) M9 pistols.

Where are the 1911s?

The March 1985 cover of NRA’s American Rifleman magazine featured a photo of the U.S. military’s just-adopted Beretta M9 pistol that replaced the venerable Model 1911A1 for general issue. The changeover from the powerful .45 ACP cartridge to the NATO compliant 9 mm Luger was as controversial as adopting a foreign pistol for America’s fighting forces.

The M1911A1 never fully disappeared from service, most notably favored by Special Forces operators, but with the bulk moving into surplus status. This year the M9 suffered the same fate as the M1911A1, replaced in favor of the modularity of another foreigner, the SIG Sauer P320. The M9s will presumably move into surplus status to share armory storehouses with the M1911A1s.

The National Defense Authorization Act of 2016 (NDAA 2016) authorized, but did not require, the Secretary of the Army to transfer the surplus M1911A1 pistols to CMP. NDAA 2018 changed “authorized” to “shall,” but as of this writing it appears the Senate will not vote on NDAA 2018 until after the August 2017 recess. The Secretary has yet to actually transfer any of the surplus M1911A1 pistols, though Johnson told SSUSA in an earlier interview that CMP has been working actively with the Army to meet transfer prerequisites, and that CMP is ready to receive the milsurp pistols.

Buying back loaners

As for rifles, there is a possible additional large but still limited resource. Several foreign countries have stocks of surplus M1 Garands acquired as loan from the U.S. under the Military Assistance Program (MAP), and many shooters and collectors are hopeful that those may eventually come home. However, CMP is not yet in that picture.

“CMP has no authority to pursue the repatriation of M1 Garands on loan to a foreign government from the U.S. Army—that’s in the hands of the U.S. Army,” Johnson said, then added a bit of hope. “The M1 Garands in the Philippines are looking good concerning repatriation by the U.S. Army,” he said, referring to an estimated 86,000 Garands that the Philippine government is poised to ship back to the states. Shooters and collectors, of course, expect the Army to subsequently pass the Garands along to CMP.

A similar number of M1s (and approximately 600,000 M1 Carbines) loaned to South Korea have been tangled in politics. “The Koreans want to sell what is not theirs to sell,” Johnson said. In 2012 South Korea announced an intention to sell the loaned Garands on the U.S. market rather than return them to the U.S. Army, apparently believing they had found a loophole in U.S. law and the MAP agreement that prohibits such loaned small arms from re-importation (small arms more than 50 years old are exempted). But re-importation still requires State Department approval which, unsurprisingly, didn’t come under the last administration. Though a bill (H.R. 1137, Collectible Firearms Protection Act) introduced earlier this year attempted to drop that requirement, that bill apparently died in committee. What authorizes South Korea to sell to U.S. importers the firearms on loan to them from the US Army for their self-defense, doesn’t appear to be addressed.

What about the M14 rifles in U.S. Army surplus racks? Is there any chance milsurp M14 rifles may eventually go to CMP? “No, due to the M14’s selective fire status,” Johnson said. “According to BATFE policy, ‘once a full auto, always a full auto.’ CMP is not allowed to take possession of M-14 rifles per our enabling legislation.”

Match fees “fall short”

The real issue for CMP, however, isn’t in acquiring the world’s last stashes of milsurp firearms, it is in finding revenues for the long-term support of its government-chartered mission to promote civilian marksmanship training. Though competitors might think match fees would cover operating costs, fees collected at major CMP events like the Western National Championships don’t even come close to covering expenses for putting on the match, much less for a sustainable business model.

“CMP match fees and sales of items on the road such as at the Western CMP Games event fall well short of profitability,” Johnson said. “None of the CMP travel games come even remotely close to breaking even. If we recover half the cost of these events, we’re lucky.” Competitors can expect match fees to increase incrementally over time to help cover the increasing costs of conducting matches.

Going retail

When CMP exhausted its supply of U.S. surplus M2 Ball ammunition for the surplus Garands, Springfields and M1917 rifles, they imported Greek surplus M2 Ball to sell; those sales continue today but, again, as with the firearms, the end is almost here. In search of open-ended revenue streams, CMP started up custom gunsmithing services for surplus rifles, conducts “build your own Garand” classes and retails commercial ammunition and commercial match grade ammunition, including uncommon calibers like 6XC and lower pressure .30-06 suitable for the Garand’s gas system, from several manufacturers. CMP also offers new commercial .22 cal. match rifles and air rifles, competition equipment from Creedmoor Sports, and has retail stores in Port Clinton, OH, and Anniston, AL, as well as online sales.

Most recently, CMP began marketing acoustic electronic scoring targets from Norwegian maker Kongsberg Target Systems. At about $2,500 per firing point, the electronic target system is the big-ticket revenue stream CMP needs. In addition to hardware sales, ongoing income from electronic targets will come from technical support and selling replacement parts.

“We have sold a few small orders and we now have a few big prospects that we feel good about in 2018,” Johnson said. “We have had no surprises concerning sales thus far; it simply takes time to prove the product’s worth and reliability.”

Competitors can expect the popularity of e-targets to increase and to see them appear at more ranges as more technology oriented shooters come into the shooting sports and old-timers begin to trust computer scoring. “The process is working very similar to that of electronic targets in air rifle [competition],” Johnson said. “Technology acceptance is driving the sale of e-targets.”

Whether CMP’s need for income is changing the game over to electronic targets, or whether CMP is bringing U.S. competitors into the 21st century to keep up with European shooters who have used e-targets for years, is perhaps a matter of perspective. Regardless, CMP is counting on retail sales even if loaned M1 Garands come home to land in CMP racks, and even if the M1911A1 pistols finally get through all the red tape.

And the M9s? It’s taken 30 years to see a potential release of the surplus M1911A1s, and the last major release of U.S. surplus arms to citizens before that were M1 Carbines released through DCM and NRA in the 1960s. There’s little reason to expect the M9s won’t spend an equal amount of time in storage.

“The CMP thinks it’s smart to wait quietly to see if we receive the 1911s,” Johnson said. “Our enabling legislation would have to change again [to receive surplus M9 pistols] and I do not see that happening for years to come, if ever. The M9s are simply not on the table for CMP.”