Smallbore History

European sport shooting dates back to the late Middle Ages where town militias defended themselves against marauders. These paramilitary “clubs” competed as a form of training, which ultimately led to the creation of formal shooting organizations beginning in 1860. Lord Frederick Sleigh Roberts is credited for contributing to the formation of the National Smallbore Rifle Association in the United Kingdom. A staunch advocate of military marksmanship training at the dawn of the 20th Century, the British soldier sought to economize training and overcome range access challenges through the use of “miniature rifles,” or smallbore rifles as we call them today.

High Power History

Other than periodic frontier shooting contests and recreational “turkey shoots,” formal shooting competition in the U.S. also has its roots in military training. During the 19th century, the military began recognizing marksmanship skill with shooting badges earned during annual requalification. For civilians, marksmanship skills were promoted by the National Rifle Association and, later, by the Civilian Marksmanship Program (CMP).

So, despite different geographical origins, both smallbore and high power shooting disciplines have ancestral ties to the military. More recently, professional military shooting teams have formed to compete internationally and to serve as a laboratory for improved shooting equipment and technique.

Members of these highly accomplished military shooting teams typically focus their training on one discipline in order to achieve high mastery. They “live, eat, breathe and sleep” their sport. It is somewhat unusual, then, to meet a competitor who crosses over to a new discipline and begins their “ascent on Mt. Everest” all over again. I met such a person during weekend shoots at a local rod and gun club. Like most shooters I know, this person’s modest focus was on achieving personal goals and helping others to do the same.

My new friend’s demeanor was so unassuming, in fact, that I felt naïve when I later learned of her accomplishments. You may recognize this partial list of her fellow U.S. Army Reserve International Rifle Team alumni: Dave Cramer, Bob Mitchell, Wanda Jewell, as well as Gary Anderson, Mike Anti, Lanny Bassham, Mike Thiemer, Margaret Murdock, Karen Monez … and the list goes on.

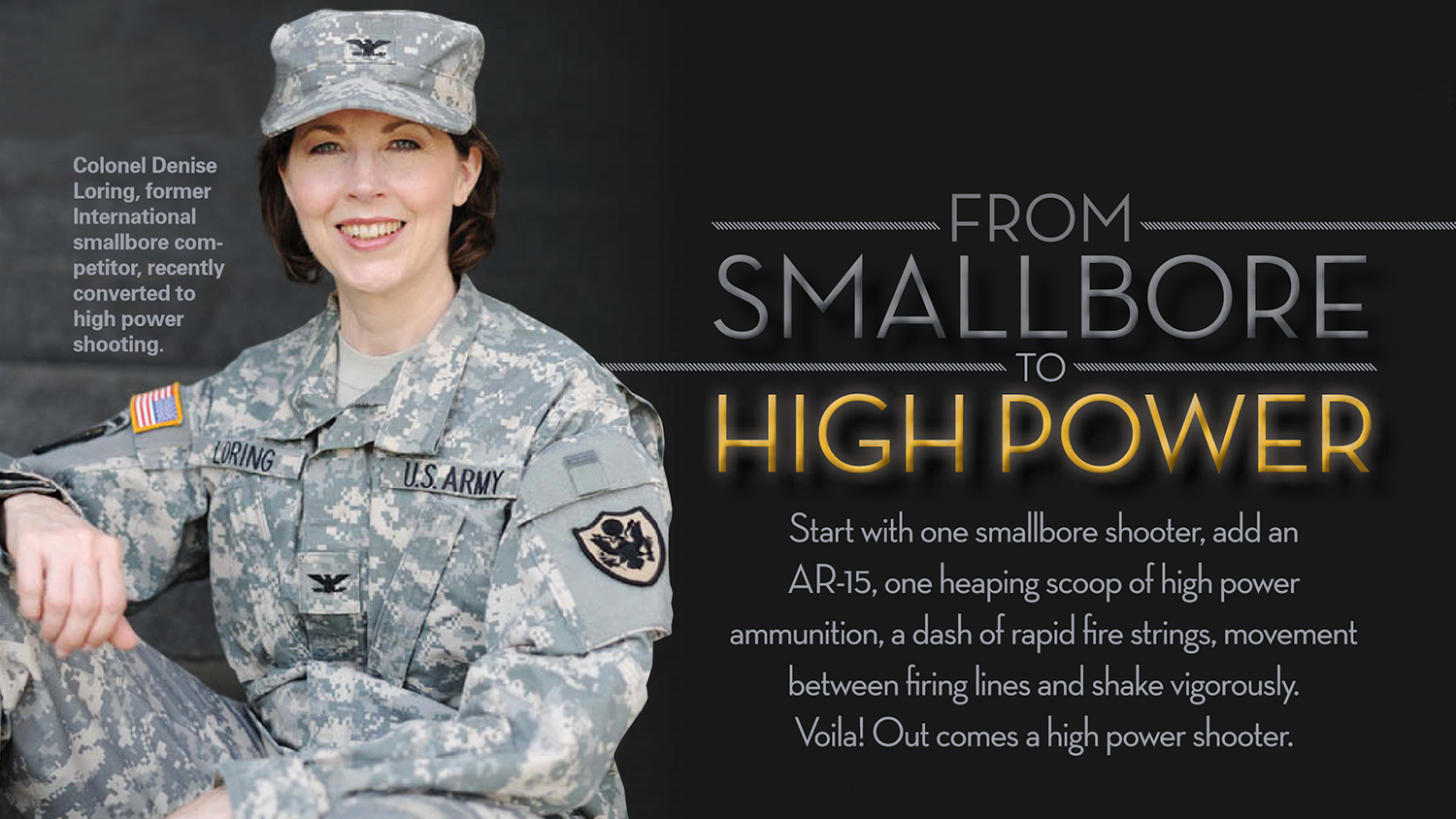

An accomplished smallbore shooter, Colonel Denise Loring had joined the local club’s spring high power league for what I assumed was a nostalgic desire to keep shooting. As pieces of her past accomplishments began to surface (rarely from her) I was curious what a national smallbore champion was doing on a high power range. Fearing that I may uncover some secret, or break with tradition among the shooting community, I was reluctant to prod, but—obviously, did.

I learned that, as the Deputy Director of Resources and Evaluation in the office of the Secretary of Defense for Reserve Affairs, she had never strayed far from her shooting roots and had, in fact, been courted by the U.S. Army Reserve (USAR) Service Rifle team to join them for the 2013 shooting season. The weekend club shoots were no walk down memory lane. She was in training.

Fast forward to the end of the 2013 season to learn that Loring had earned a master rating in high power. Questions began piling up in my head: Are the disciplines so similar? Is she unique? Wasn’t the high power recoil distracting? How can one successfully move from aperture to iron sights in one season? Smallbore shooters don’t use “come-ups” for sight settings and don’t reload .22LR rounds.

After some gentle pestering, (she may disagree with “gentle”), Colonel Loring agreed to share notes and observations from her shooting diary in an attempt to identify key learning experiences that might benefit others new to high power rifle.

From Loring: “First of all, I don’t want to seem elitist or aloof talking about other shooters’ progress coming up through the classifications. I don’t want anyone to feel badly that they are not progressing at the same rate as I did. It really is not about where you are classified. It is more important that people come back year in and year out to enjoy this great pastime."

“I realized at Camp Perry how challenging it can be to progress up the high power classifications. I was fortunate to tap into many coaches on several levels; the club level, the military level with veteran shooters on the USAR Service Rifle Team, and 'old school' high power shooters who used to compete ‘back in the day’, and still have advice that is relevant. Everyone was integral in contributing to the final outcome by nurturing my love and appreciation for rifle shooting.”

When were you active with the USAR International Smallbore Rifle Team?

I was recruited in 1985 from King’s College in Wilkes-Barre, PA, by the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit (AMU), Fort Benning, GA. I served two tours of duty with the AMU and then transitioned from active duty to the reserves. I joined the USAR International Rifle team in 1994.

Did you ever think you’d get back to smallbore as a competitor?

I did. In the summer of 2012 I dug out all of my smallbore equipment, took an inventory and reached out to a local shooter at the Fairfax Rod and Gun Club. I started training again in just prone. My shooting jacket still fit, but the pants just wouldn’t work [laughs]. I was coaxed into shooting a Conventional Prone match that was hosted at the club; iron sights on Saturday and scope on Sunday. I started training every weekend. You would have thought I was prepping for the Olympic Games. I worked with two shooters at the club who brought back memories of how to shoot again, along with referring back to my shooting diary to see how I had last set up the equipment in 1998. I appreciated the coaching to prep for the match and shot my first 1600 on scope day.

What was your reaction when you were invited to return to competition, but on the Service Rifle team?

We have a high power contingent at the Fairfax Rod and Gun Club and I was invited to shoot with them. The match director knew I was a rifle shooter and thought I would like a change. I own an AR-15 that I purchased in the 1990s, thinking I would try high power someday, so it sounded like fun. At least I would get it sighted in. After I shot at a couple of club “fun matches” I reconnected with the USAR team and asked the Service Rifle officer-in-charge what kind of scores I needed to get on the team. After submitting my club scores, he called and said I had made the cutoff for the development team. I was excited at the prospect to compete for the USAR team again.

What about high power rifle did you find different than smallbore and how did you master them?

Sighters. I was very nervous about only having two sighters for NRA high power matches. Then, I heard about the CMP style of high power where there are no sighters and could not believe you could shoot a match without them. We have unlimited sighters in smallbore and I took full advantage of that aspect. In NRA conventional smallbore you can even return to the sighter bull once you have begun shooting for record.

Zeros. When I shot smallbore, I did not know how many clicks I was up/down for elevation or windage. I just got into position, got sighted in and then went for record. I was quickly educated during high power practice about having a “zero” on the rifle. When shooting at the local club, I only needed a 200-yard zero. Then I learned I needed to get solid zeros for the 300- and 600-yard lines, so I headed to a range in Pennsylvania for a day of training. There I learned even more about recording zeros in the data book, how zeros will change with temperatures and how the zero on one range does not mean it will be the same on another range. I mastered zeros by writing them down, keeping track of how many clicks I was putting on the sights, and practiced on as many different ranges as I could. My data book was especially important for CMP Excellence in Competition (EIC) matches where sighters aren’t permitted. I made sure I shot an across-the course match at the same range so I would have solid zeros. With the extra preparation, I was confident the day I shot and came away with six more points towards “distinguished.”

Rapid Fire. The rapid fire (RF) was a new experience too. We don’t shoot RF in smallbore so this sounded like fun. I was given a shot timer so I could train for the 60-second RF sitting and the 70-second RF prone. It took some time for me to get the cadence down. Friends at the local club would come out and train with me so we could time each other and mark each other’s shots. I’m not sure I have mastered RF yet, but I have shot strings of 100, and even shot a 200 sitting last year. I didn’t know the tradition of having your target saved when you shoot your first clean target, so I didn’t call for that target. I’m still learning.

Pits. Which brings me to learning the pit service. We do not have pit service in smallbore. We have target systems that are mostly electronic for International-style shooting, so you simply learn how to work the target control box on your firing point. For conventional smallbore, we hang the paper targets on the frame and change them out for each stage of fire. High power meant learning a whole new lingo for scoring, procedures for inadequate shots, or excess shots in RF strings. I find the pit time to be fun and very social. You meet some interesting people from all across the country during pit duty at Camp Perry.

How does the wind differ between smallbore and high power?

International smallbore is shot from 50 meters with cover on three sides, so the wind does not blow directly on the shooter. Smallbore shooters watch the flags and the mirage, wait for a desired wind condition and shoot until the condition changes. Having the wind blowing directly on me at Camp Perry during high power last summer was a challenge. Now I am looking for nearby windy ranges to train on. Moving the sights to compensate for wind out at 600 yards is new to me too. I had to learn how to determine direction, use new tools to read wind speed and put a wind call together. There’s no other way to learn it other than lots of practice.

What are your favorite high power positions?

I work on standing and sitting positions the most. I figure since standing is the toughest, I need to put about 50 percent of my training time on that position. I put 40 percent into RF for timing and position practice, and then that last 10 percent on slow fire prone. Of course, maybe my slow fire prone scores would come up if I worked on them a little more [smiles].

What are the similarities between smallbore and high power?

In both disciplines we keep a lot of notes. I always used a shooting diary in smallbore for equipment, analyzing score trends and changes to positions. For high power, I keep notes in the data book, with sight zeros being a huge part of that data, along with wind/light information.

Editor’s Note: Denise Loring’s first article was published in SSUSA earlier this year.