WARNING: All technical data in this publication, especially for handloading, reflect the limited experience of individuals using specific tools, products, equipment and components under specific conditions and circumstances not necessarily reported in the article and over which the National Rifle Association (NRA) has no control. The data has not otherwise been tested or verified by the NRA. The NRA, its agents, officers and employees accept no responsibility for the results obtained by persons using such data and disclaim all liability for any consequential injuries or damages.

Since you're reading Shooting Sports USA, it's a safe bet you're not one of those shooters who fires a gun just once a year—the week before deer season to double check last year's sight settings. You probably shoot quite a bit. Perhaps you're a competitor in one or more shooting disciplines. You may be a junior, high school or college team coach. You may even be a certified NRA instructor. At the very least, you take a more serious approach to shooting than most gun owners. If any or all of the above apply to you, there's something more you can do to further increase the satisfaction you get out of shooting: reloading.

Some of you may already be avid reloaders; in that case, what follows may be familiar to you (though it never hurts to review). Most of you, however, have only a passing familiarity with reloading—gleaned, perhaps from a magazine article or while watching a friend or relative prepare some loads in his/her basement. This article is the first in a series designed to present the theory and practice of the reloader's art, from the most basic steps to advanced techniques for serious competitive shooting.

What is Reloading?

The NRA Guide to Reloading, defines reloading as "...remanufacturing of a cartridge to its former complete state." This is performed by carefully reassembling the four components of a metallic cartridge—case, primer, powder charge and bullet—using specialized tools and techniques. At its most basic level, reloading simply produces ammunition that fires reliably and safely in a particular gun. Beyond that, however—and this is where the art comes in—a skillful reloader can produces loads that are tailored to give optimum performance in relation to a specific gun, target and distance, even taking into consideration such variables as ambient temperature, air density and throat erosion.

Why Reload?

For the average shooter, economy is perhaps the most common reason. Reloaded cartridges can cost less than half of what comparable factory rounds cost. For competitive shooters, however, reloading has other, more significant benefits. By selecting the proper components and the proper amount and type of powder, the reloader can create a load for a specific event, such as the Palma Match or the Wimbledon Cup. Also, maximum accuracy in a given rifle or handgun is usually obtained only with reloaded ammunition. It is no coincidence that reloads are used by all serious benchrest and high power rifle competitors (except in those matches in which reloads are prohibited). Additionally, for match shooters who use wildcat cartridges (cartridges that are not loaded by a factory) reloading is the only way to make such ammunition.

Ammunition and Ammunition Components

The case is perhaps the heart of any cartridge; modern cartridge cases may be straight, tapered or bottleneck in shape and may have rimmed, rimless, semi-rimmed, belted and rebated-rimless case heads.

What is most critical for the reloader to understand is that there are significant variations among cartridge components. Cases for the same cartridge can vary in wall thickness, internal volume and even internal construction. Primers can vary in brisance (explosive power). Bullets of the same nominal diameter, weight and style can differ in actual diameter, jacket hardness, bearing surface and nose profile. Powders differ in chemical composition, granule size and shape, burning rate and much more. These variations (variations that can be observed among components form different manufacturers and even among components of different lots from the same manufacturer) can affect both the safety and the performance of a reloaded cartridge.

The Reloading Process

There are basically five steps in reloading a metallic rifle or handgun cartridge. First, the case must be resized, or reformed to its original dimensions. This is essential, because the case expands slightly when a cartridge is fired. Next, the spent primer must be removed (also called depriming or decapping) and a fresh primer inserted into the primer pocket. Then the case is recharged with the proper amount and type of powder. Finally, a bullet is inserted into the case mouth, where it is held in place by neck tension and often a slight constriction at the mouth called a crimp. Additionally, the reloader must inspect the components—particularly the case—before starting the reloading process and must additionally inspect and label the finished, reloaded cartridges.

Reloading Equipment

Reloading is accomplished through the use of specialized reloading tools. Chief among these is the reloading press. The press is a device in which the basic steps of reloading are performed. The reloading press allows the mounting of both the cartridge case and the reloading dies for that cartridge and has a linkage mechanism that allows the case to be run forcefully into the die. Single-stage presses allow one die to be mounted and thus perform only one operation at a time, while several dies can be mounted in multi-stage and progressive presses, allowing several operations to be performed simultaneously. Shell holders are used to mount cases with different head sizes in the press.

Reloading dies are hardened steel tools that are mounted in the press and perform various operations on the case. Dies com in sets for various calibers—most sets for rifles consist of two dies, while most pistol caliber sets consist of three dies. In two-die rifle sets, one dies resizes the case body and case neck while decapping or depriming the case; the other seats the bullet and sometimes crimps the case mouth. In three-die pistol or rifle sets, an additional die is included that bells or flares the case mouth for easier bullet insertion. Some four-die sets are made that also include a separate crimp die.

Reloading dies are hardened steel tools that are mounted in the press and perform various operations on the case. Dies com in sets for various calibers—most sets for rifles consist of two dies, while most pistol caliber sets consist of three dies. In two-die rifle sets, one dies resizes the case body and case neck while decapping or depriming the case; the other seats the bullet and sometimes crimps the case mouth. In three-die pistol or rifle sets, an additional die is included that bells or flares the case mouth for easier bullet insertion. Some four-die sets are made that also include a separate crimp die.

Measuring the proper weight of powder for each load is done with a reloading scale capable of measuring to 1/10 grain. Both beam-type and electronic scales are available. When faster reloading is desired than can be achieved through weighing each charge, you can use a powder measure—a device for metering a precise amount of powder into a case with the turn of a crank. The weight of the powder charge as dispensed must be verified with a reloading scale.

For safety and proper performance, cases and finished cartridges must be held to certain precise dimensions; this requires an accurate dial caliper capable of measuring to .001". Dial calipers can also be used to verify other critical component dimensions, such as bullet diameters.

While some presses have a mechanism for seating a fresh primer in the case, others do not and a separate priming tool must be used. Also, cases lengthen slightly each time they are fired and must eventually be trimmed back to a standard dimension using a case trimmer.

Other useful tools include a deburring tool to deburr and chamfer the case mouth for easier bullet insertion; a primer pocket cleaner to eliminate powder residue, grit, etc. from the primer pocket; case cleaning machines to remove residue and dirt from the spent cases; a powder funnel to guide powder into the case mouth and case loading blocks to organize the cases in batches.

Additionally, the reloader must have a selection of recent reloading manuals to cross-check and compare load data, a clean workbench or table where reloading can be done in a safe and organized manner and eye protection that must be worn at all times while reloading.

Reloading Manuals and Other Sources of Information

Most of the major manufacturers of reloading components publish reloading manuals. In addition to information on reloading tools and technique, these books contain load data, which can be viewed as recipes for specific loads. The load data for a specific cartridge will tell you exactly the brand of case and primer, the brand and weight of powder as well as the brand, weight and type of bullet that can all be safely combined to make a cartridge. This data is developed in professional ballistics laboratories and are pressure-tested for safety and uniformity.

Additionally, information on loads, equipment and techniques can be found in many books as well as in articles in magazines such as Shooting Sports USA, American Rifleman and many others. Get your loader and materials ready because in subsequent articles, we will explore in detail the sequence of steps involved in loading a rifle cartridge and in testing a load for accuracy.

Since you're reading Shooting Sports USA, it's a safe bet you're not one of those shooters who fires a gun just once a year—the week before deer season to double check last year's sight settings. You probably shoot quite a bit. Perhaps you're a competitor in one or more shooting disciplines. You may be a junior, high school or college team coach. You may even be a certified NRA instructor. At the very least, you take a more serious approach to shooting than most gun owners. If any or all of the above apply to you, there's something more you can do to further increase the satisfaction you get out of shooting: reloading.

Some of you may already be avid reloaders; in that case, what follows may be familiar to you (though it never hurts to review). Most of you, however, have only a passing familiarity with reloading—gleaned, perhaps from a magazine article or while watching a friend or relative prepare some loads in his/her basement. This article is the first in a series designed to present the theory and practice of the reloader's art, from the most basic steps to advanced techniques for serious competitive shooting.

What is Reloading?

The NRA Guide to Reloading, defines reloading as "...remanufacturing of a cartridge to its former complete state." This is performed by carefully reassembling the four components of a metallic cartridge—case, primer, powder charge and bullet—using specialized tools and techniques. At its most basic level, reloading simply produces ammunition that fires reliably and safely in a particular gun. Beyond that, however—and this is where the art comes in—a skillful reloader can produces loads that are tailored to give optimum performance in relation to a specific gun, target and distance, even taking into consideration such variables as ambient temperature, air density and throat erosion.

The basic steps of metallic cartridge reloading including (A) resizing the case, (B) removing the spent primer [decapping], (C) expanding the inside of the neck to the proper diameter, (D) slightly belling the case mouth to more easily accept the bullet [done primarily with handgun cartridge cases], (E) priming the case, (F) charging the case with powder and (G) seating the bullet. Crimping is often performed during the seating operation.

Why Reload?

For the average shooter, economy is perhaps the most common reason. Reloaded cartridges can cost less than half of what comparable factory rounds cost. For competitive shooters, however, reloading has other, more significant benefits. By selecting the proper components and the proper amount and type of powder, the reloader can create a load for a specific event, such as the Palma Match or the Wimbledon Cup. Also, maximum accuracy in a given rifle or handgun is usually obtained only with reloaded ammunition. It is no coincidence that reloads are used by all serious benchrest and high power rifle competitors (except in those matches in which reloads are prohibited). Additionally, for match shooters who use wildcat cartridges (cartridges that are not loaded by a factory) reloading is the only way to make such ammunition.

Ammunition and Ammunition Components

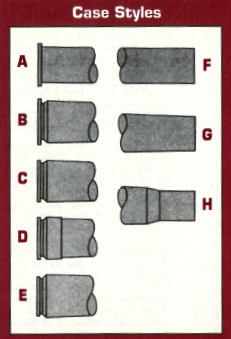

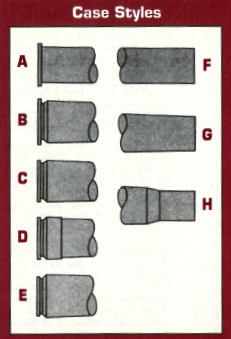

The case is perhaps the heart of any cartridge; modern cartridge cases may be straight, tapered or bottleneck in shape and may have rimmed, rimless, semi-rimmed, belted and rebated-rimless case heads.

What is most critical for the reloader to understand is that there are significant variations among cartridge components. Cases for the same cartridge can vary in wall thickness, internal volume and even internal construction. Primers can vary in brisance (explosive power). Bullets of the same nominal diameter, weight and style can differ in actual diameter, jacket hardness, bearing surface and nose profile. Powders differ in chemical composition, granule size and shape, burning rate and much more. These variations (variations that can be observed among components form different manufacturers and even among components of different lots from the same manufacturer) can affect both the safety and the performance of a reloaded cartridge.

The Reloading Process

There are basically five steps in reloading a metallic rifle or handgun cartridge. First, the case must be resized, or reformed to its original dimensions. This is essential, because the case expands slightly when a cartridge is fired. Next, the spent primer must be removed (also called depriming or decapping) and a fresh primer inserted into the primer pocket. Then the case is recharged with the proper amount and type of powder. Finally, a bullet is inserted into the case mouth, where it is held in place by neck tension and often a slight constriction at the mouth called a crimp. Additionally, the reloader must inspect the components—particularly the case—before starting the reloading process and must additionally inspect and label the finished, reloaded cartridges.

Reloading Equipment

Reloading is accomplished through the use of specialized reloading tools. Chief among these is the reloading press. The press is a device in which the basic steps of reloading are performed. The reloading press allows the mounting of both the cartridge case and the reloading dies for that cartridge and has a linkage mechanism that allows the case to be run forcefully into the die. Single-stage presses allow one die to be mounted and thus perform only one operation at a time, while several dies can be mounted in multi-stage and progressive presses, allowing several operations to be performed simultaneously. Shell holders are used to mount cases with different head sizes in the press.

Case head styles include rimmed (A), semi-rimmed (B), rimless (C), rimless belted (D) and rebated rimless (E). Body styles include straight (F), tapered (G) and bottleneck (H).

Measuring the proper weight of powder for each load is done with a reloading scale capable of measuring to 1/10 grain. Both beam-type and electronic scales are available. When faster reloading is desired than can be achieved through weighing each charge, you can use a powder measure—a device for metering a precise amount of powder into a case with the turn of a crank. The weight of the powder charge as dispensed must be verified with a reloading scale.

For safety and proper performance, cases and finished cartridges must be held to certain precise dimensions; this requires an accurate dial caliper capable of measuring to .001". Dial calipers can also be used to verify other critical component dimensions, such as bullet diameters.

While some presses have a mechanism for seating a fresh primer in the case, others do not and a separate priming tool must be used. Also, cases lengthen slightly each time they are fired and must eventually be trimmed back to a standard dimension using a case trimmer.

Other useful tools include a deburring tool to deburr and chamfer the case mouth for easier bullet insertion; a primer pocket cleaner to eliminate powder residue, grit, etc. from the primer pocket; case cleaning machines to remove residue and dirt from the spent cases; a powder funnel to guide powder into the case mouth and case loading blocks to organize the cases in batches.

Additionally, the reloader must have a selection of recent reloading manuals to cross-check and compare load data, a clean workbench or table where reloading can be done in a safe and organized manner and eye protection that must be worn at all times while reloading.

Reloading Manuals and Other Sources of Information

Most of the major manufacturers of reloading components publish reloading manuals. In addition to information on reloading tools and technique, these books contain load data, which can be viewed as recipes for specific loads. The load data for a specific cartridge will tell you exactly the brand of case and primer, the brand and weight of powder as well as the brand, weight and type of bullet that can all be safely combined to make a cartridge. This data is developed in professional ballistics laboratories and are pressure-tested for safety and uniformity.

Additionally, information on loads, equipment and techniques can be found in many books as well as in articles in magazines such as Shooting Sports USA, American Rifleman and many others. Get your loader and materials ready because in subsequent articles, we will explore in detail the sequence of steps involved in loading a rifle cartridge and in testing a load for accuracy.